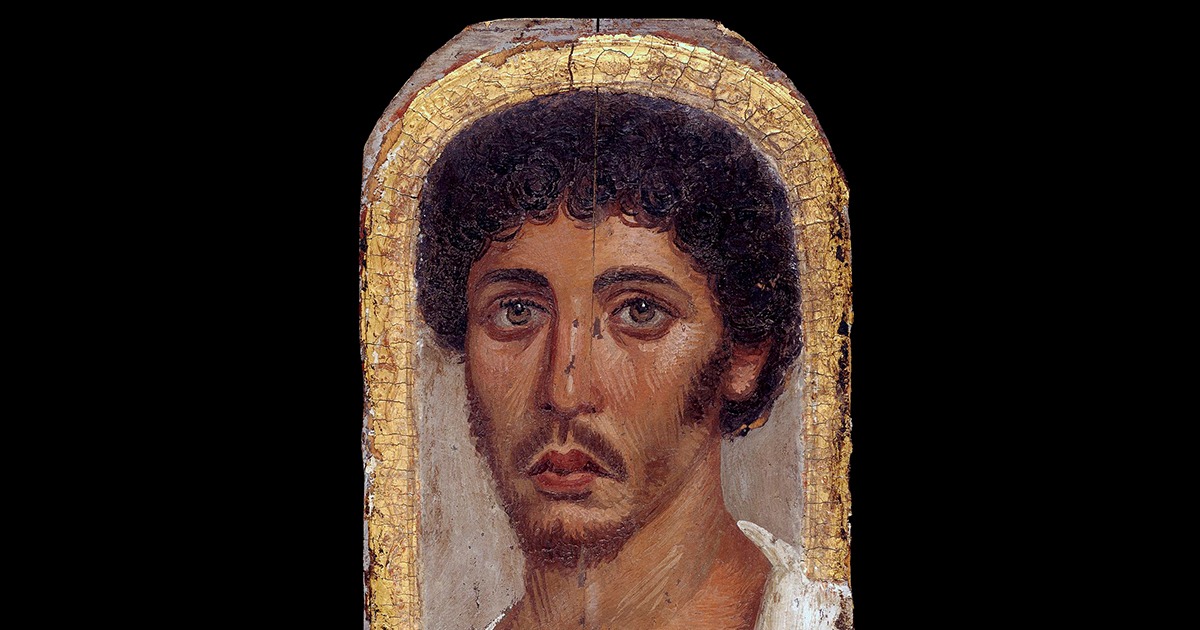

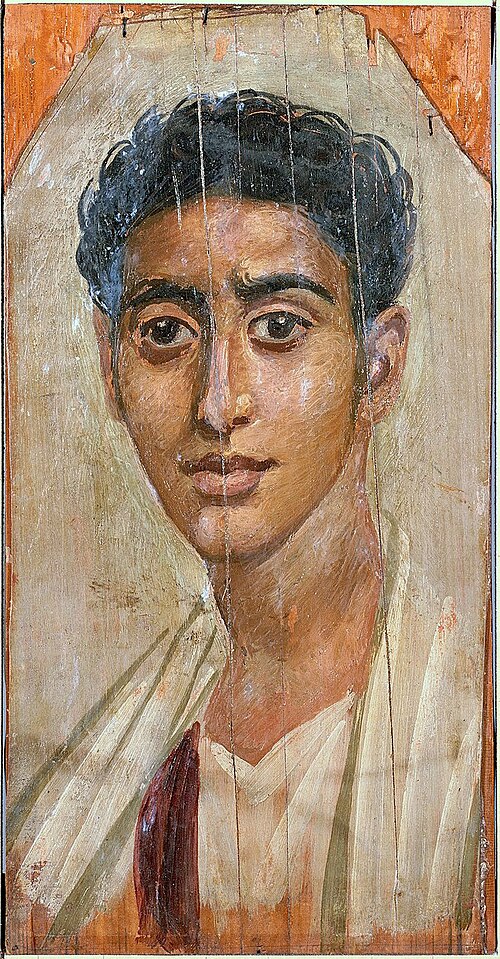

Walk into a gallery that holds the Fayum mummy portraits and you meet people, not statues. Faces in three-quarter view. Pupils caught with bright points of light. Heads turned slightly, as if a conversation paused a heartbeat ago. These are images made in Roman Egypt, mostly between the first and third centuries CE, painted on wooden panels and set over the faces of the dead. They are also among the most direct encounters we have with antiquity: a moment when a painter’s hand tries to pin a living presence to a thin board of wood.

The label “Fayum” comes from the oasis south-west of Cairo, a region that yielded many examples, although similar portraits turn up across Roman-era Egypt. The style is Greco-Roman, the purpose is Egyptian, and the result is something singular: a merger of techniques and beliefs that still feels immediate. Museums prized them once they reached Europe in the nineteenth century, yet it has taken careful archaeology and modern science to explain how they were made, where they travelled, and why they endure.

What the portraits are, and what they are for

Each panel is a wooden support — often limewood or linden, sometimes cedar or cypress — covered with a white ground and painted in either hot wax (encaustic) or tempera. The portrait was attached to the mummy wrappings over the face. In life, it may have hung at home; in death, it kept vigil. This dual role matters. The painter’s job was not only to flatter or describe, but to secure identity for the journey after burial. Hence the attention to individual features: a beauty mark, a scar, a turned lip, a fashionable curl.

The dates vary by workshop and site, yet most belong to the first three centuries CE. Hairstyles help with chronology; so do jewellery types, clothing details, and the way the pupils and irises are painted. Portraits that look strikingly “modern” often sit in this window, when Roman taste favoured realism and a play of light across skin.

How they were made: wax, water, wood

Two techniques dominate. Encaustic mixes pigments with molten beeswax. Tempera binds pigments in water with animal glue or another protein. Both can be rich and precise, though they behave differently under the brush. Encaustic allows painterly, almost oily modelling; tempera builds thin, matte layers with crisp edges.

Encaustic: heat, sheen, and depth

In encaustic portraits the flesh glows. Artists worked warm wax with brushes and heated tools, pushing and fusing strokes into soft transitions. Highlights could be literally raised — a ridge of wax catching light on the cheek or eyelid. Reds from ochres and madder lakes, blacks from carbon, and lead white play across faces. Gold leaf sometimes brightened wreaths or backgrounds, particularly in portraits of the fashionable or well-to-do.

Tempera: speed, clarity, and line

Tempera portraits read as cooler and flatter, with delicate hatching and sharply drawn contours. Because the medium dries quickly, painters laid down decisive strokes, especially around eyes and hair. Seen close, the brushwork maps the painter’s order of operations: pupils, then irises; lashes last; hair in small, direction-aware lines.

Faces in context: life, status, and fashion

These were not royal images. They belonged to people from towns and villages who could afford a panel and a skilled hand. Many sitters carry Greek names; some have Egyptian names rendered in Greek. Clothing and jewellery mirror Roman taste: cloaks with purple clavi, wreaths of gilded leaves, earrings with pearls. Hairstyles track imperial fashion with surprising accuracy, giving curators a way to bracket dates. A woman’s piled curls or a man’s beard length can narrow a portrait to a span of decades.

Age and expression vary. Infants peer solemnly, teenagers look composed, elders gaze with a heavy calm. A few carry inscriptions. One famous panel names a boy called Eutyches; others add scraps of information that suggest status or origin. None of it feels generic. Even when a workshop repeats a formula — a favourite pose, a standard necklace — the painter shifts features to keep the person before them intact.

Workshops and working methods

Evidence points to local workshops serving nearby communities. Painters reused panel sizes and proportions; carpenters prepared boards with standard thicknesses. Tool marks on the reverse, saw kerfs, and dowel holes suggest patterns in manufacture. Painters probably kept design habits: where to place the highlight in the iris, how to build a curl, which brown to use for hair underpainting. When several portraits share the same quirks, curators propose hands or “masters” at work in a single shop.

There is also proof of collaboration. Goldsmiths handled leaf and ornament; carpenters cut frames; embalmers stitched panels into wrappings. A portrait might begin in a studio and end in a funerary space, with last touches added after the body was bound — for example, gilded borders applied once the panel sat flush with the wrappings.

What science has added

The past decade has transformed the technical study of these panels. Museum scientists now use imaging and spectroscopy to map pigments, binders, and even trace resins. A collaborative network, focused on ancient panel paintings, has pooled results so that a portrait in New York can be compared with one in London or Los Angeles. This has clarified what the eye already suspects: different workshops developed distinct recipes, and painters freely switched between encaustic and tempera depending on cost, fashion, or training.

One discovery gets particular attention. A synthetic pigment called Egyptian blue, known from pharaonic art, shows up in these portraits in small, strategic doses. Under visible-induced luminescence imaging, it glows in the near-infrared, revealing where artists used tiny particles to cool shadows or give life to veins and eyelids. The effect is invisible in normal light, yet it shapes the look. That trick — a whisper of blue in the flesh — helps explain why the skin reads as convincing rather than flat.

Wood, wax, and time

Analyses of the support confirm what object labels often note: lime/linden is common, with occasional cedar, cypress, or sycamore fig. Dendrological study is rare because panels are thin, but species ID by microscopy is robust. Wax composition mostly points to beeswax; tempera binders show animal glue. Coatings applied in later centuries sometimes complicate the surface; conservators now characterise and, where safe, reduce those layers so the original paint can breathe again.

From excavation to gallery wall

The modern story begins with nineteenth-century digs and dealers. Systematic excavations at cemeteries in the Fayum brought the first large groups to light in the 1880s and again in the early years of the twentieth century. Some panels remained attached to mummies; others were removed and sold. Early handling could be rough by today’s standards, but it created the first catalogues and exhibitions that introduced the portraits to the public. Since then, major museums have acquired strong groups, and research has accelerated through loans and collaborative projects.

That history also leaves us with duties. Provenance research is active. Conservation ethics have matured. Museums now share technical data and images under open licences when possible. The more that records from past seasons and dealers are digitised, the better our picture of where a panel came from and how it moved.

Reading a portrait: clues at a glance

Stand in front of one and try a checklist. Look at the eyes: many show a large iris and deep pupil with a bright, offset highlight. That catchlight anchors the gaze. Study the mouth: a slight asymmetry keeps it lifelike. Trace the hair: encaustic strokes can sit proud of the surface, while tempera strands stay flat and linear. Notice jewellery: a gilded wreath or pearl drop earring may point to Roman fashions from a particular reign. Follow the garment lines: a narrow purple clavus signals rank and Roman taste.

Then step back. The realism is not photographic. It is interpretive, designed to capture a presence. Painters build illusion from a short list of moves — highlight, shadow, contour, gloss — and it works because the choices are economical and confident.

Why they matter now

Art historians prize these panels because they preserve Greco-Roman painting where so little else survives. Archaeologists value them because they document a local society navigating empire, language, and belief. Conservators like them because they test technique. For the rest of us, the attraction is simpler. You meet someone’s eyes across two millennia and feel, briefly, that the distance is smaller than the date suggests.

There is also a lesson about cultural mixture. The portraits fuse imported style and native ritual without awkwardness. A Roman necklace sits comfortably on an Egyptian afterlife. The combination is not a compromise; it is a solution to living in a complex world.

Where to see them

Strong groups live in London, New York, Los Angeles, and other cities. Some museums display panels beside wrapped bodies to restore context; others gather them in quiet rooms where you can study brushwork at nose length. More institutions now release high-resolution images with open licences, which helps scholars and publishers — and makes it easier for readers to see details at home.

How to read them with care

Because many portraits were removed from mummies long ago, context can be patchy. Dates sometimes rely on style more than excavation records. That is why technical projects matter: wood species, tool marks, and pigment choices can link scattered panels back to workshops and regions. When a group of portraits shares identical board widths, saw marks, and paint mixtures, you can start to rebuild a community of makers and patrons.

Meanwhile, display matters. A portrait hung as a painting on a wall reads one way; set into linen wrappings, it reads another. Museums that show both views help visitors understand the ritual role without losing the intimacy of the face-to-face encounter.

A note on care and conservation

Panel portraits are fragile. Wood moves with humidity; wax softens with heat; protein binders dislike damp. Modern mounting systems allow the boards to flex gently. Conservators keep light levels modest and temperatures steady. When older varnishes or restorations cloud the surface, careful cleaning can recover the original clarity of the skin tones and the sparkle in jewellery.

Imaging has become non-invasive and revealing. Multispectral photographs isolate pigments; X-rays map nails and joins; reflectance shows underdrawing. Sometimes the tests find Egyptian blue in places the eye would never expect, tucked into shadows or mixed into flesh. Small findings like that add up to larger insights into how painters built lifelike faces with very simple means.

Seeing them well

If you visit, give each panel time. Move sideways to watch the catchlights shift. Step back to see how the head turns into space. Look for the tiny asymmetries that break symmetry and make a face breathe. Then, read the label for the workshop’s date and the medium. When you leave the room, you will likely remember an expression rather than a name. That is as the makers intended.