Pompeii’s walls do not whisper about sex. They speak plainly. In dining rooms and shops, over doorways and in side chambers, images of desire, potency, and luck appear with a confidence that can surprise modern visitors. To the Romans, erotic imagery was not a taboo to hide behind curtains. It was a language. A phallus could bless a doorway. A bedroom scene could signal service in a brothel or simply play with myth. A god like Priapus could boast at the threshold and promise abundance within. Read this visual code and the city grows clearer, not cruder.

Much of that code is symbolic. A phallus is luck. A wreath hints at victory. A satyr and maenad mean wine and loosened rules. At other times, the message is literal. A small chamber off a side street shows a couple on a bed, and the context leaves little doubt about the room’s business. Yet even these scenes carried more than titillation. They signalled price, position, hierarchy, and humour in a very Roman way. Sex, in Pompeii, worked as commerce, ritual, and joke all at once.

Why explicit images stood at the door

Take the famous Priapus at the House of the Vettii. He weighs his phallus against a bag of money while fruit spills from a basket at his feet. It is a welcome and a boast. The household claims prosperity and asks the god to keep it flowing. Placing him at the entrance was not a prank; it was good sense. The image guards against envy, invites fertility, and lets guests know this is a house that enjoys plenty. It blends piety and performance with a wink that Roman visitors would recognise.

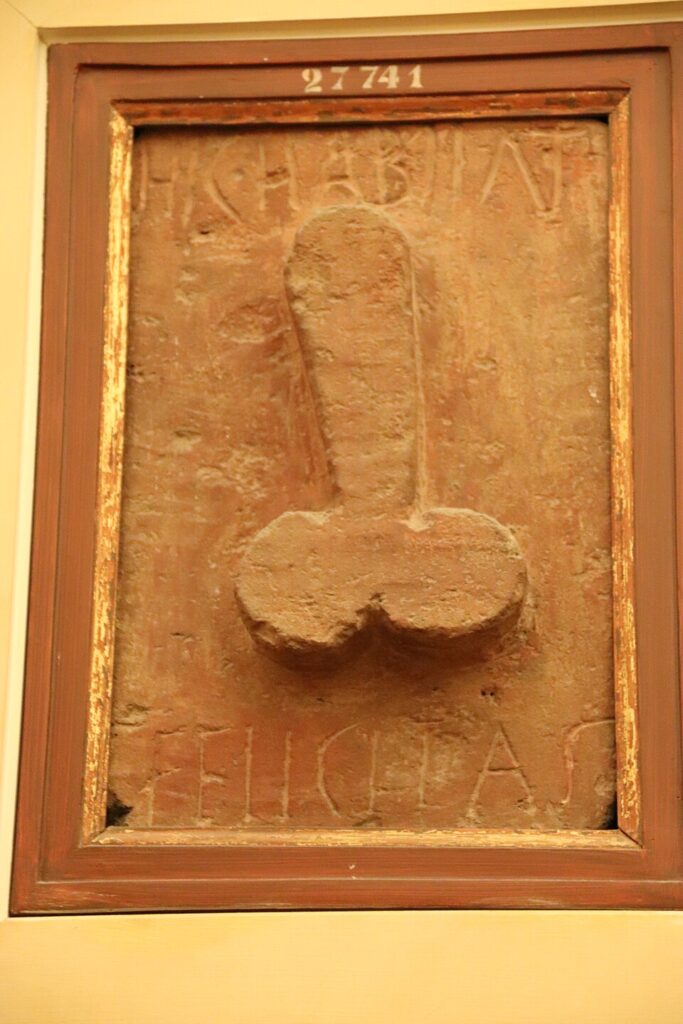

Across town similar signs appear on bakeries and workshops. A carved phallus over an oven promises luck for the day’s loaves. Another over a lintel promises the same for trade. Simple, bold, and effective, these symbols belong to the Roman habit of using images as apotropaic tools. A strong emblem deflects the evil eye. It turns attention into protection.

Erotic panels in the Lupanar

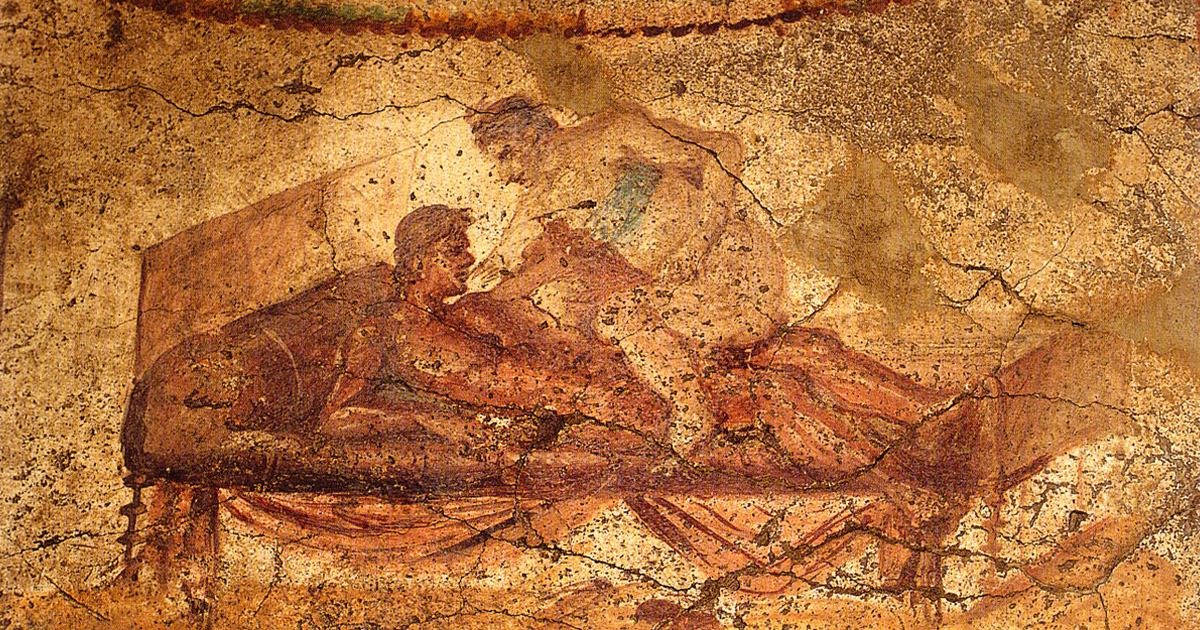

Pompeii’s best-known brothel, the Lupanar, still holds small paintings over the doors of tiny rooms. Each shows a couple on a bed. One scene leans tender; another, acrobatic. Scholars often describe them as a visual “menu”, a shorthand for services that transcended literacy. They also set a mood. Clients saw what the place offered before stepping into a cubiculum scarcely wider than an outstretched arm. The frankness is striking, yet the tone is tidy. Beds are made; sheets are drawn; the bodies are idealised. The panels state the business without grime.

Elsewhere, small side rooms in houses show scenes just as direct. Were these private spaces for pleasure, hired rooms, or jokes to amuse dinner guests. Context matters. A painting placed off a kitchen reads differently from one beside a courtyard. Archaeology studies the plaster joins, the floor levels, and the wear patterns to decide which is which. Even so, the line between entertainment and instruction remains thin. Romans liked to blur it.

Sex as symbol: the phallus as good luck

Not every erotic image is about sex. Many function as protection. The Romans called a phallic charm a fascinum. You find them in metal, in terracotta, and on walls, sometimes with small bells attached. People wore them. Shopkeepers hung them. Households placed them near thresholds. Laughter was part of the magic. A comically exaggerated charm made onlookers grin, and in that grin the evil eye lost its sting. In Pompeii, this kind of object is everywhere once you start to look.

Tintinnabula — little wind chimes hung with phallic forms and bells — served the same purpose. A rattle of sound and a flash of bawdy humour together fended off bad luck. Many were later gathered into the “Secret Cabinet” in Naples, a collection once opened by special request only. Today, they hang in well-lit galleries as evidence of a culture happy to meet misfortune with noise and nerve.

Myth plays along

Roman painters often use myth to code desire. A satyr toys with a maenad. Dionysus finds Ariadne asleep and claims her as bride. Hermaphroditus startles a leering Silenus. These scenes decorate dining rooms and reception spaces, usually in the Fourth Style mix of architectural fantasy and cameo-like panels. They allow talk about pleasure, freedom, and danger without naming any guest. They also turn a dinner into a small theatre. The walls set the theme; the conversation does the rest.

Priapus, too, straddles symbol and story. In gardens he stands as guardian of vines and fruit trees. On walls he becomes a pun on wealth and virility. The House of the Vettii puts him front and centre in the vestibule. The message lands even if you skip the footnotes. Here is plenty. Here is power held lightly enough to joke about it.

Gender, power, and the Roman joke

Modern viewers sometimes read these images as simply male display. The story is more tangled. Women appear as patrons and sitters in domestic portraits; they also host scenes that set the tone for a feast. Brothel panels do objectify, yet the business model relied on the labour and presence of women and enslaved people whose lives the paintings rarely show. Meanwhile, the city’s graffiti records jokes, boasts, crude insults, and occasional tenderness in both male and female voices.

Roman humour liked reversal. A tiny figure carrying an absurdly outsized phallus pokes fun at bravado. A god who is both obscene and holy makes a point about the way power works. Laughter relaxes social rules for a moment and reveals who can bend them. The walls grin; the diners follow.

How painters built the scenes

Technically, these are frescoes. Artists spread fine plaster in sections and painted while the surface was still wet. Pigments bound into the lime, creating durable colour. In small erotic panels, the palette is tight: warm reds, ochres, carbon black, and quick white highlights. Figures sit on simple beds with crisp sheets and a red line to mark the edge. The economy suits the subject. A few strokes establish a thigh, a hand, a look over the shoulder. In larger mythological scenes, the brushwork loosens and the settings expand, yet the language remains economical and clear.

Some workshops built extensive programmes room by room. Floors, walls, and even ceiling motifs speak to each other. A tidy border frames the lively content. A painter who could model an eyelid with a single stroke earned good fees. When the painter’s hand appears in several houses, curators start talking about local “schools” or named masters. The city was a hive of such teams by the late first century.

Reading the rooms

Erotic imagery in a reception room does not turn the house into a brothel. It sets a tone for dining that welcomes frankness, wine, and witty speech. In sleeping chambers, small amorous scenes could bless the couple’s bed or simply echo fashionable taste. In brothels, painted panels at the door of each cubiculum help an anxious client choose. In shops, phallic signs work as good-luck charms and, sometimes, as playful advertisements. Context decides meaning. The same phallus that guards a bakery oven would feel out of place in a shrine to the household gods, unless the family liked a joke at the gods’ expense.

Street signs add another layer. A carving shaped like a phallus might point down a lane. Some guides claim these arrows led clients to brothels. That makes a neat story. It is not the only reading. Many such images simply mark good fortune, the presence of a successful shop, or the hope that envy will pass by without harm. The best answer, as often in archaeology, is “sometimes”.

The “Secret Cabinet” and changing taste

When the first great finds from Pompeii and Herculaneum reached Naples in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, curators quickly locked away objects that seemed indecent. Thus began the Gabinetto Segreto, a room within the Naples Archaeological Museum where erotica could be viewed by mature men who asked politely. Policies shifted with fashion and politics. Today the room is open, with warnings for families, and the scholarship is frank. What earlier generations saw as embarrassment, we now read as culture.

This history of display matters because it shaped early writing on Pompeii. For decades, elegant mythological panels were praised while erotic signs were ignored or hidden. The result was a distorted city, tasteful but unreal. Restoring the bawdy pieces to the story brings the place back to life. You cannot understand Roman humour, protection, or hospitality without them.

Commerce, status, and the erotic wall

Sex sold, of course, but it also signalled status. A house that could afford a full Fourth Style programme, with myth panels and ornament, could also afford a playful Priapus at the door. A bakery that carved a neat fascinum above the oven announced prosperity and invited more. Even brothels had image budgets. A run of small panels over the doors suggested management with pride in the premises. Painters translated these needs into crisp scenes that resisted soot, steam, and time.

Meanwhile, the city’s trade in images was lively. Workshops kept pattern books and reused compositions. Certain couples on a bed return again and again, with the angle tweaked or the sheet pulled differently. These were not television stills; they were efficient signals that said enough without fuss.

The moral weather of the house

Roman religion slid easily between temple and table. A household altar (a lararium) might show a snake of abundance beside the family’s guiding spirits. Nearby, a small erotic scene could mark fertility and joy, while a phallic charm guarded the door. No one saw tension here. The divine liked laughter and wine as much as sacrifice and incense. When Dionysian imagery fills a dining room, it invites guests to relax their tongues, sing, and let wit run swift.

These choices made the moral “weather” of the house. A prim set of panels might suit an older couple. A racier run could fit a host who liked to shock. Either way, visitors registered the room’s temperature at a glance.

What is symbol, what is sex

Modern viewers often ask for a firm line. Which images are pure symbol and which are porn. The line is blurry by design. Romans expected images to do several jobs at once. A phallus warded off harm and boasted of virility. A brothel scene informed and entertained. A myth panel flattered the host’s taste and set a theme for talk. Call them erotic if you like, but remember that meaning in Pompeii sits on several stools. Leave one out and the picture limps.

Even measurements can mislead. The famous Priapus is comically over-endowed. That is the joke. It is also the point. Abundance, not anatomy, is the subject. The money bag on the pan answers the scale. Fruit spills from a basket. The city gets the message in a heartbeat.

Technique and touch

In small panels the painter’s hand is the star. The contour of a shoulder rests on a single line, thickening as it turns under the arm. Shading on a thigh arrives as a soft haze of red-brown. Whites pop on the knuckles, the eye, the sheet edge. With so few strokes, the body comes together. That economy feels modern. It also explains why the paintings still look fresh. The fewer the moves, the fewer the failures.

Large myth panels bring a different pleasure. Here, tiny details reward time: a sandal’s strap, a grape’s highlight, a satyr’s grin drawn with the lightest touch. Painters understood that viewers would sit for hours at a meal. The wall must hold attention without draining it.

How to look without blushing

Start with the frame. Many panels sit inside painted architecture, with columns and friezes that pretend to be marble or gilt. That frame tells you to read the panel like a cameo. Next, clock the symbols. Laurels mean victory; grape vines mean wine; a phallus means luck and fertility. Then, let your eye meet the figures. When a panel sits over a tiny room with a masonry bed, you can guess the function. When it sits in a smart dining room, it may be teasing or mythic rather than literal.

If you bring children, pick your route. Many museums and sites now use discrete signage and give parents choices. The point is not to hide the past, but to meet it on your own terms.

Misreadings and careful corrections

Tidy stories travel fast. Not all survive scrutiny. The idea that every street phallus points to a brothel is one of them. Some surely did. Many did not. Similarly, not every erotic panel marks a sex worker’s room. Context, again, is king. Archaeology is patient, and the city rewards patience. Layer by layer, the rooms tell the truth.

When a claim feels too neat, check the details. Is the panel over a real bed or a plaster shelf. Is there a latrine nearby. Do lamp soot and floor wear match a busy venue or a tidy private space. Answers to such questions cool hot takes without killing curiosity.

Why this matters now

Pompeii’s erotic imagery is art history, yes, but it also sharpens how we think about symbols in public space. A culture may place the same image on a shrine, a shop, and a joke plaque without confusion. Meanings stack. Modern cities do this too, just with different emblems. Studying Pompeii helps us see that flexibility and resist easy binaries.

There is also comfort in honesty. The ancients admitted desire, fear, and luck into their daily decor. They built humour into protection and made space for frankness at dinner. You do not need to approve of every choice to admire the confidence. The walls said what the city meant.

Visiting today

The Archaeological Park of Pompeii presents these works with context and care. The House of the Vettii has reopened after long restoration, its walls gleaming, its priapic threshold intact. The Lupanar remains small and crowded, a reminder that commerce once fit into tight corners. Naples holds the famous “Secret Cabinet” with bronze charms and rude lamps. Signs warn; doors remain open. Scholars continue to refine labels as new studies appear. The result is a city easier to read each year.

Give yourself time with the images. Step close, then back away. Watch how a single white dot turns an eye alive. Notice how a sheet’s red edge holds the bed in place. Smile at a charm that made Romans laugh. In the end, the best response to Pompeii’s erotica is the one Romans planned: delight, tempered by good sense.

The long afterlife of a short joke

The phallic relief with the legend hic habitat felicitas — “happiness lives here” — has become a minor celebrity. It condenses the Roman habit of folding fortune, fertility, and humour into a single sign. You can read it as bravado, charm, or both. Bakers carved it near ovens. Shopkeepers set it by doors. The phrase survives because it is good copy: compact, cheerful, and just cheeky enough to keep envy away.

Nearby, bells tinkle from a tintinnabulum, and a small bronze amulet dangles from a necklace. Each item works the same magic. Turn the gaze. Make the watcher laugh. Convert malice into a grin. In a city that lived with risk, this strategy suited people who wanted to move on with their day.

Ethics of display and the family visit

Sites and museums face old questions in new ways. What do we show. How do we label it. Where do we warn. Recent practice trusts visitors and gives them choices. Clear signs mark rooms that contain explicit imagery. Guides explain symbolism without sniggering. Teachers use myth panels to discuss consent, power, and performance in ancient literature. The goal is not to sensationalise, but to restore balance. Sex is one thread in a larger fabric of daily life, faith, and trade.

Handled well, these objects teach agility. Viewers learn to hold two ideas at once: that an image can be frank and still function as ritual; that a joke can also be a prayer.

Looking ahead

Conservation will keep refining the colours and lines we see today. As soot lifts, as salts retreat, as lost corners reappear, details sharpen. Scholars continue to probe workshop patterns, link portraits to owners, and test old claims. Fresh finds at the park bring new sparks to a long-running conversation about how Romans blended ritual, humour, and desire in public view.

For now, the city remains a rare place where you can test your eye against another culture’s confidence. The walls will not blush. You do not have to either. Read the symbols, enjoy the wit, and carry the lessons home.