In a small press room at the University of Crete this February, a panel of archaeologists, linguists, and computer scientists sat behind a table covered in photographs of clay tablets. These were not just any tablets — they were inscribed in Linear A, the ancient Minoan script that has been an enigma for over a century. The announcement they made was careful, even restrained, but it still carried the weight of a landmark moment: they believe they have deciphered a meaningful portion of the language using artificial intelligence trained in both linguistic structure and archaeological context.

“We’re not claiming the entire code is cracked,” said Dr. Irini Alexandri, the project’s co-lead. “But for the first time, we have a consistent set of readings that fit the archaeological evidence, the linguistic patterns, and the internal logic of the script.” Her words were measured, but the excitement in the room was not hard to feel. The first coherent phrases in a language silent for three and a half millennia may finally be taking shape.

The script that kept its secrets

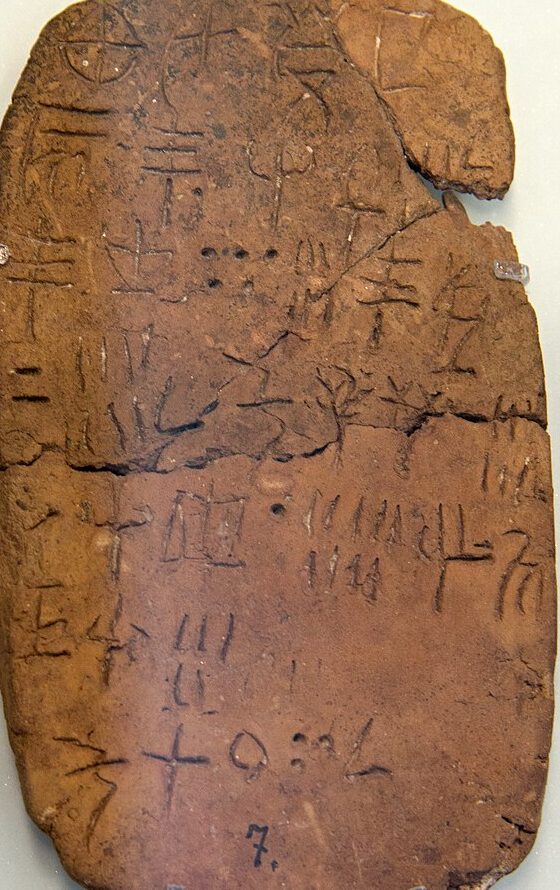

Linear A is the writing system of the Minoan civilisation, which flourished on Crete and neighbouring islands between roughly 2000 and 1450 BC. It is the predecessor to Linear B, the Mycenaean Greek script deciphered in 1952 by Michael Ventris and John Chadwick. Linear A looks deceptively similar to Linear B — many symbols are the same or nearly so — yet the language it encodes is different. It is not Greek, and so far it has resisted firm identification with any known ancient tongue.

The surviving corpus is frustratingly small: around 1,400 inscriptions, most of them only a few words long, found on clay tablets, seal impressions, stone vessels, and ritual objects. Without a “Rosetta Stone” — a bilingual text to match the signs to known words — decipherment has been a slow grind of comparison and hypothesis.

AI joins the decipherment effort

The 2025 breakthrough is the result of a four-year project combining the archives of the British School at Athens, the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, and excavation records from sites including Hagia Triada, Phaistos, and Knossos. The team’s AI system was trained not only on images of the script but also on the principles of morphology and syntax from hundreds of ancient languages, ranging from Sumerian to Etruscan. “We didn’t feed it modern Greek or English and hope for the best,” explained computational linguist Dr. Tomas Weber. “We trained it on the kinds of structures you see in early administrative writing.”

Previous digital attempts often stalled because Linear A’s dataset is too small for conventional machine learning. This project adapted techniques from bioinformatics, where patterns must be detected in genetic sequences that are short, irregular, and ancient in origin. The algorithm looked for recurring sign clusters, analysed their position in relation to numerical symbols, and cross-referenced them with the archaeological function of the object they were found on.

From signs to meaning

What emerged from the analysis is a provisional vocabulary of about 70 words. Many appear to refer to commodities — barley, olive oil, wine, textiles — alongside personal names, place names, and administrative terms. Some readings overlap with Linear B in sign form but differ in language, suggesting that the Minoan tongue borrowed or shared signs with its Mycenaean successors while preserving its own lexicon.

One recurring sequence, found on tablets from both Hagia Triada and Phaistos, is believed to denote a religious title or office. Another appears consistently next to numbers and units of measurement, almost certainly indicating a trade good. When the algorithm applied these readings across the corpus, patterns began to align: storerooms, workshops, and shrines each had their own clusters of terms, hinting at the division of Minoan life into economic, craft, and ceremonial spheres.

A festival in the records?

Among the more striking cases is a group of tablets from Hagia Triada that may record goods allocated for a festival. The inscriptions list quantities of oil and wine, paired with the suspected title for a religious role, followed by what might be a place name. The repetition across several tablets suggests an organised distribution rather than random accounting. If correct, it would be our first clear window into Minoan ceremonial logistics, written in their own words.

For Dr. Alexandri, this is where the breakthrough matters most. “It’s not just about translating isolated words,” she said. “It’s about understanding the system of thought — how they categorised their world, how they recorded obligations, and how ritual and economy intertwined.”

The caution of experience

Not all specialists are convinced. Professor Alexis Vassilakis, a veteran of Aegean epigraphy, welcomed the fresh approach but warned against premature celebration. “AI is powerful, but it is also capable of producing very persuasive nonsense,” he told reporters. Without external confirmation — ideally, a bilingual inscription — the readings remain hypotheses. He noted that the decipherment of Linear B, often compared here, succeeded only when sign values were matched with a known language.

The research team agrees, describing their work as a platform for further testing rather than a final translation. They have invited colleagues worldwide to challenge and refine the readings, and plan to release both the database and the AI methodology later this year.

Why Linear A matters

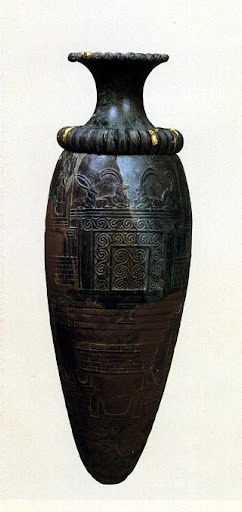

Linear A is more than a puzzle for epigraphers. It is the administrative voice of the Minoan civilisation — a society that influenced Mycenaean Greece and, through it, much of later Mediterranean culture. The Minoans left us dazzling frescoes, complex palaces, and an island-wide network of trade, but without their language we have been forced to interpret them through the lens of outsiders. Each word deciphered brings us closer to hearing their own accounts of their economy, beliefs, and political order.

The stakes also extend beyond Crete. Techniques developed here could aid the study of other stubborn scripts: the Indus signs of South Asia, the Etruscan inscriptions of Italy, even the rongorongo tablets of Easter Island. The combination of archaeological context and AI’s pattern recognition could become a standard tool in the historian’s kit.

Inside a Minoan archive

Picture a storeroom in Hagia Triada around 1450 BC. Clay tablets, damp from recent moulding, are laid out on wooden shelves. A scribe bends over one, pressing a stylus into the soft surface, recording the delivery of wool to a workshop. In the corner, another scribe tallies jars of oil destined for a nearby shrine. The language is familiar to them, invisible to us — until now.

The AI-driven translations have allowed for experimental readings of some tablets that bring such scenes into focus. A Phaistos tablet seems to track shipments of grain from three different estates; a Knossos fragment pairs a commodity term with what may be the name of a coastal settlement. None of these are sensational revelations, but they are the texture of a functioning society, captured in a script once thought unreadable.

From archive to algorithm

One of the project’s most innovative features is its integration of excavation metadata into the AI’s reasoning. A word found exclusively on ritual vessels was tagged differently from one that appeared on shipping records. By feeding the system these contextual weights, the team aimed to anchor proposed meanings in the lived realities of Minoan society. This reduced the temptation to impose neat patterns that make statistical sense but fail archaeological scrutiny.

“It’s about letting the script speak within its own world,” said Dr. Weber. “A word on a libation table isn’t just a string of signs — it’s part of a specific act in a specific place. We try to preserve that connection.”

The road ahead

The coming months will test the resilience of the 2025 findings. Excavations on Crete and the Cycladic islands continue to produce occasional new examples of Linear A, and each will serve as a check on the AI’s vocabulary. If the readings hold, they may eventually allow for longer translations and a fuller grammar. If they falter, they will still have narrowed the field of plausible interpretations.

Meanwhile, museums are preparing to update their displays. In Heraklion, curators are considering adding “working translations” beneath some Linear A tablets, with a note explaining their tentative nature. It is an unusual move, but one they hope will bring the public into the decipherment process rather than waiting decades for a final verdict.

A quieter kind of breakthrough

There is no single eureka moment here, no headline-ready “translation” of a grand epic or royal decree. Instead, the breakthrough is about method: showing that the fusion of archaeological context, historical linguistics, and machine learning can produce credible, testable results where each discipline alone has stalled. It is also about patience — the willingness to build meaning sign by sign, knowing that certainty will come slowly.

For Dr. Alexandri, that is fitting. “These people lived in cycles of seasons, festivals, and trade. Their language reflects that rhythm. We should expect its recovery to follow a similar pace.”

And so, the work continues. Somewhere in a museum drawer or an unexcavated storeroom lies a tablet that will confirm or confound the AI’s readings. When it surfaces, the conversation will begin again — in the voices of the Minoans, just a little clearer than before.