Nergal and Ereshkigal sit at the heart of the Mesopotamian imagination. He governs plague, war, and the scorching heat that withers fields. She rules the Great Below, a land without return where the dead drink dust and the gates creak on their hinges. Together they form a partnership that explains how order holds beneath the earth while famine, fever, and conflict press on the living. Their marriage is not a soft romance. It is a political arrangement set on a cosmic stage, with tempers, tests, retreats, and reconciliations. That tension is exactly why their story lasts.

Ancient scribes told their tale in different ways. Sometimes Nergal crashes into the underworld and seizes power by force. At other times he returns in shame, then comes back with gifts, patience, and a plan. The variations matter less than the recurring idea. Power in the world below must be shared, and the forces that trouble human life have a seat at Ereshkigal’s table. When the couple balances each other, the seasons settle and the cities breathe again. When they do not, the surface world feels it.

Who they are, in plain terms

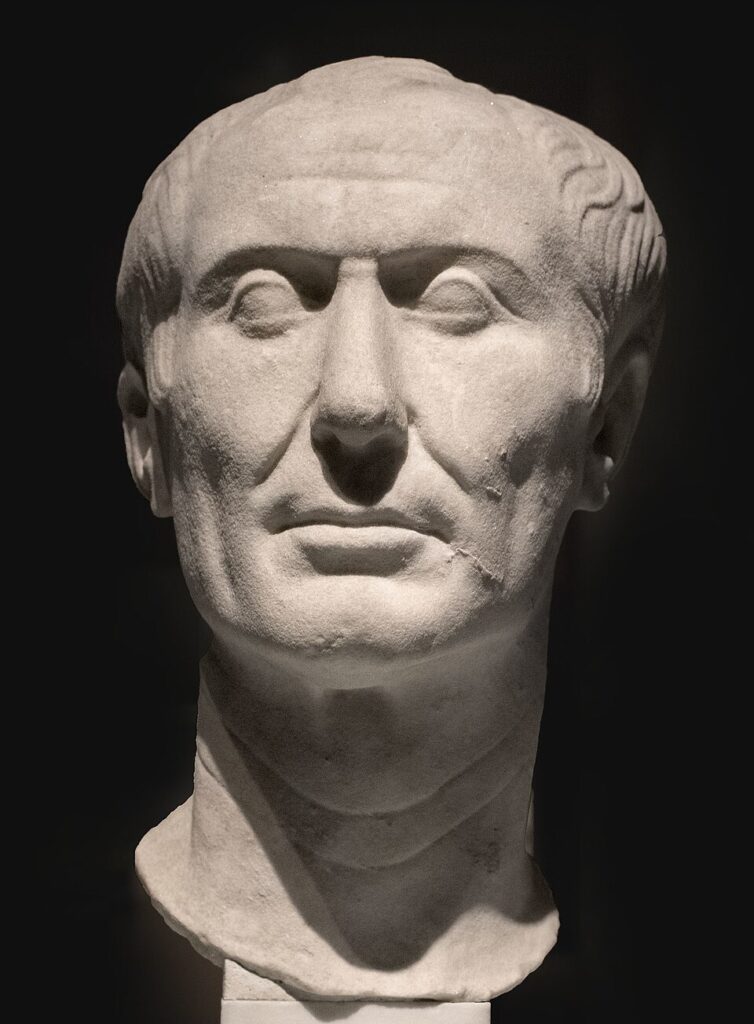

Nergal’s roots run to Kutha, a city north of Babylon, where he held court in the temple called E-meslam. He is a god of extremes. Summer’s killing glare, epidemic disease, battlefield ruin: all belong to his sphere. Yet he also protects borders and punishes injustice. In some texts his name shifts to Erra, a warlike aspect who strides out with weapons bared. The lion, the mace with a fierce head, and the open gate are his signs. He is not subtle. He is the heat you feel on your skin when noon becomes a threat.

Ereshkigal is different in tone. She does not roam. She reigns. Her city is Irkalla, her palace stands by Ganzir, the vast gate of the dead, and her servants include Namtar, the herald who carries fate. Where other gods drink beer and plan wars, Ereshkigal sits, listens, and accepts the new arrivals. No one escapes her court. She is not evil; she is inevitable. The scribes describe her as the sister of Inanna, which places her inside the highest circle of divine kinship. That link matters when disputes spill across worlds.

The underworld they rule

Mesopotamian cosmology layers the universe like a house. Heaven above holds the bright gods. Earth belongs to people, animals, and the daily grind. The underworld lies below, shadowed yet orderly. It is not a place of torture for the wicked or reward for saints. It is a realm where dust is food and silence stretches long. The dead pass seven gates in a strict sequence. Each gate takes a garment or jewel, stripping pride and status until only a bare person enters the throne room.

That formality is the point. The underworld is a court, not a chaos. Ereshkigal sits as queen. Nergal sits beside her when the stories end in balance. Judges and scribes record each arrival. Demons, often called galla, act as officials. The scene is grim yet precise, like an office that never closes. This order matters for the living. If the gates hold and the court works, crops can grow. If they fail, ghosts wander, disease spreads, and the sun burns too hard.

How the two meet: a tale with several turns

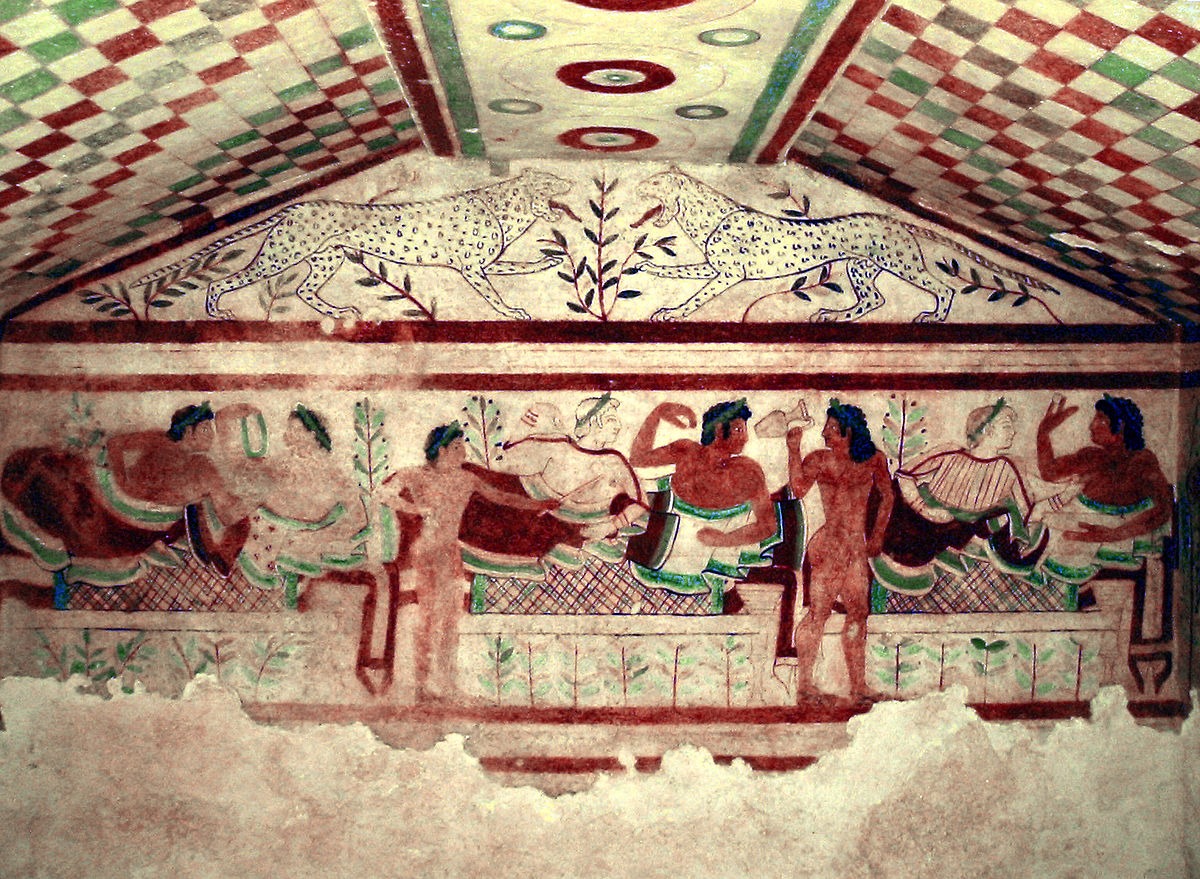

One classic version begins at a banquet in the world above. All the great gods attend, but Ereshkigal sends her herald in her place, since queens of the Great Below do not travel lightly. The assembly rises for the envoy. Everyone stands except Nergal. It is a slight. Namtar notices and reports back. Ereshkigal demands that the offender come down to apologise.

Nergal prepares. Some deities, wary of the underworld, offer tools and warnings. He brings offerings, spells, and a plan to avoid the gatekeepers’ traps. Seven gates open, one by one. Each time, a guard asks for a token, and Nergal yields a piece of protective gear. He enters, stripped of charms, yet unbowed. What happens next depends on the tablet you read. In one version, Ereshkigal falls for him and they spend six days and nights together. On the seventh, he slips away, returning to the upper world without farewell.

Return, anger, and a second descent

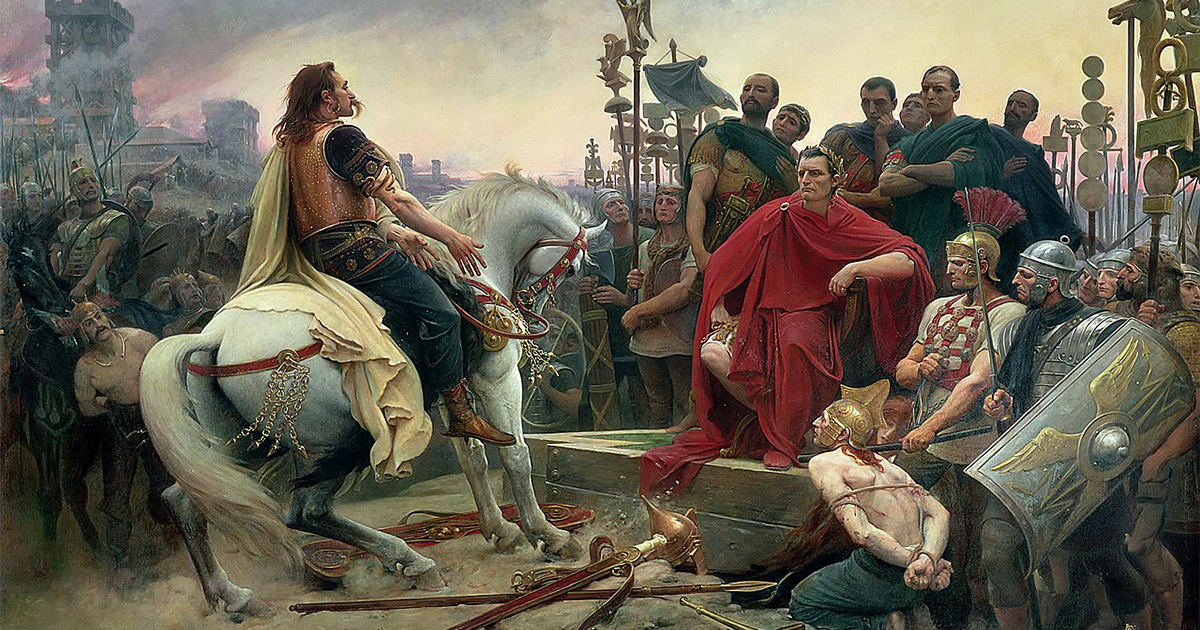

Ereshkigal does not let insults pass. She sends Namtar to demand her lover’s return. The gods above try to shield Nergal. He refuses to hide. Instead, he descends again, this time with clear intent. At the gates, he repeats the ritual and walks straight to the throne. He seizes Ereshkigal by the hair. The scene is harsh to modern eyes, yet in the logic of the myth it signals a reshaping of power. He pulls her from the throne, yet he does not kill her. He marries her. From that point, they share the rule of the Great Below.

The story is often read as a mix of courtship and conquest. It is also a political fable. The violent god of heat and plague does not stay outside the system. He is brought inside, placed on a seat, and bound by bonds of kinship. Order absorbs force. The underworld gains a second ruler who can tame outbreaks and accept penalties. Ereshkigal gains a partner who understands the hot edge of suffering. Both gains matter.

Linked myths: Inanna’s descent and the cost of power

To see how this marriage fits the wider myth cycle, put it beside the descent of Inanna, also known as Ishtar. In that poem, the goddess of love and war enters Ereshkigal’s realm to extend her influence. The queen orders each gatekeeper to take a piece of jewellery or clothing. By the time Inanna stands before the throne, she is naked and powerless. The seven judges fix a gaze on her. She dies. Only careful rescue rituals and a grim bargain bring her back. Someone must take her place in the Great Below.

Set this alongside the Nergal tale and a pattern emerges. No one, not even a great goddess, walks into the underworld on charisma. Gifts and plans can help. So can courage. Yet the gate sequence strips titles and status until raw identity remains. In the end, power there depends on Ereshkigal’s consent or a negotiated order. Marriage to Nergal is one such order. It does not erase the queen’s authority. It complements it.

What their marriage explains

Ancient audiences did not treat myths as idle entertainment. Stories worked as tools. This tale explains why plagues end, why summers finally break, and why the dead stay put. When Nergal accepts a place beside Ereshkigal, his wild energy feeds the system rather than tearing it. Epidemics have limits. The sun relents after harvest. The court below processes the dead in order. The city above can hold festivals again.

The marriage also carries a warning. If Nergal storms off, fever returns. If Ereshkigal rages without balance, grief floods the streets. Cooperation holds the world together. Marriage is the image that makes that point easy to remember, even for those who do not read tablets.

Rituals, offerings, and the living

Ritual life on the surface mirrors this logic. Families poured water and set food for ancestors in practices often called kispu. Priests marked the days when the gates opened a crack to allow messages to pass. City officials consulted omens when disease struck, seeking to know whether Nergal’s hand had fallen in anger. If so, they made offerings at his temple in Kutha and asked him to sheathe the mace. At the same time, Ereshkigal received gifts by name. Two altars, one plea. The pair must be addressed together.

Text and practice move in step. When the couple agree, funeral rites run clean and quiet. When they do not, the line between the living and the dead blurs. Ghosts hover at doorways. Sleep thins. Crops fail. No one needed philosophy to grasp the lesson. Keep the rulers below on speaking terms and the gates will swing smoothly on their hinges.

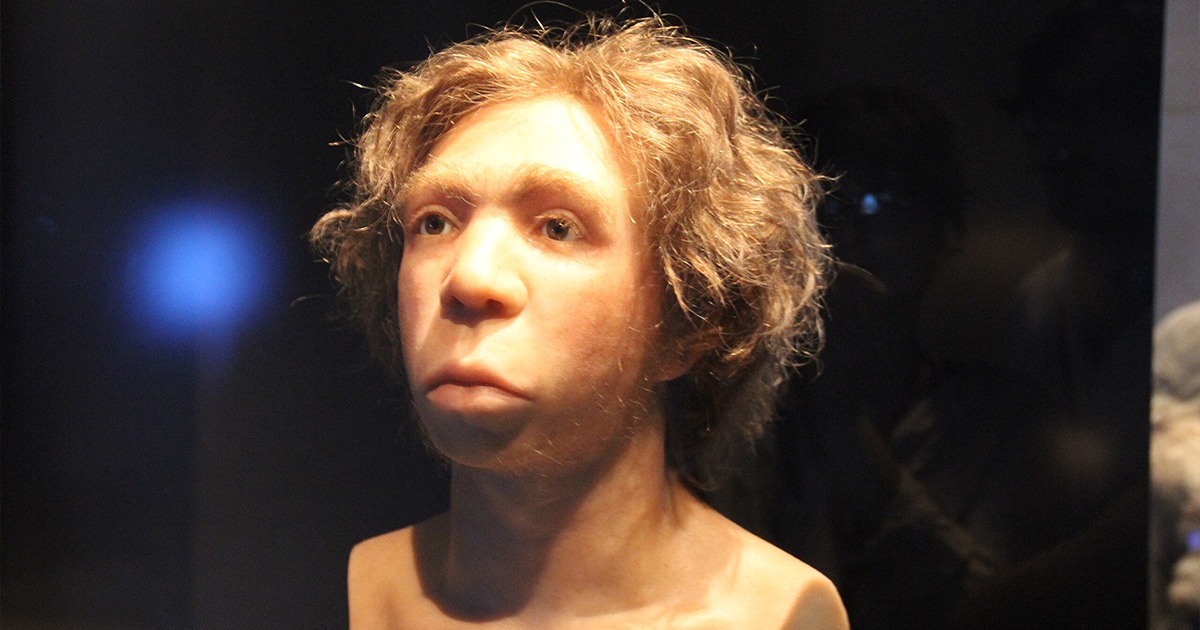

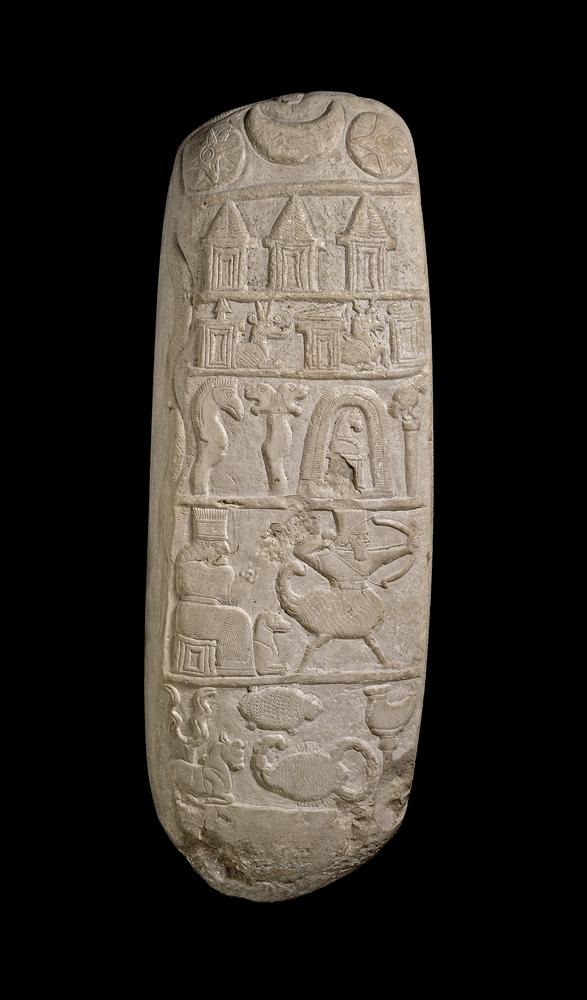

The look and feel of their images

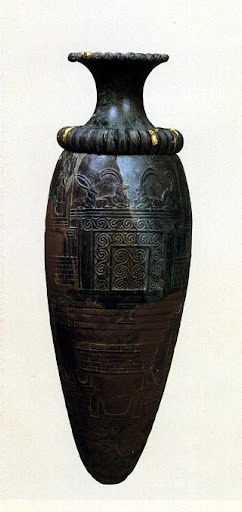

Ereshkigal is rarely labelled in art, which invites debate. Some plaques and reliefs with wings, taloned feet, and a crown of horns have been read as her image by later scholars. Others argue for Ishtar. The exact identification matters less than the shared signals of sovereignty and night. Nergal’s signs are plainer. A lion-headed mace appears on boundary stones, and the god sometimes stands with a sword, a scimitar, or a club. The pair together rarely appear as a portrait, yet their symbols often share space in temple inventories and lists of divine processions.

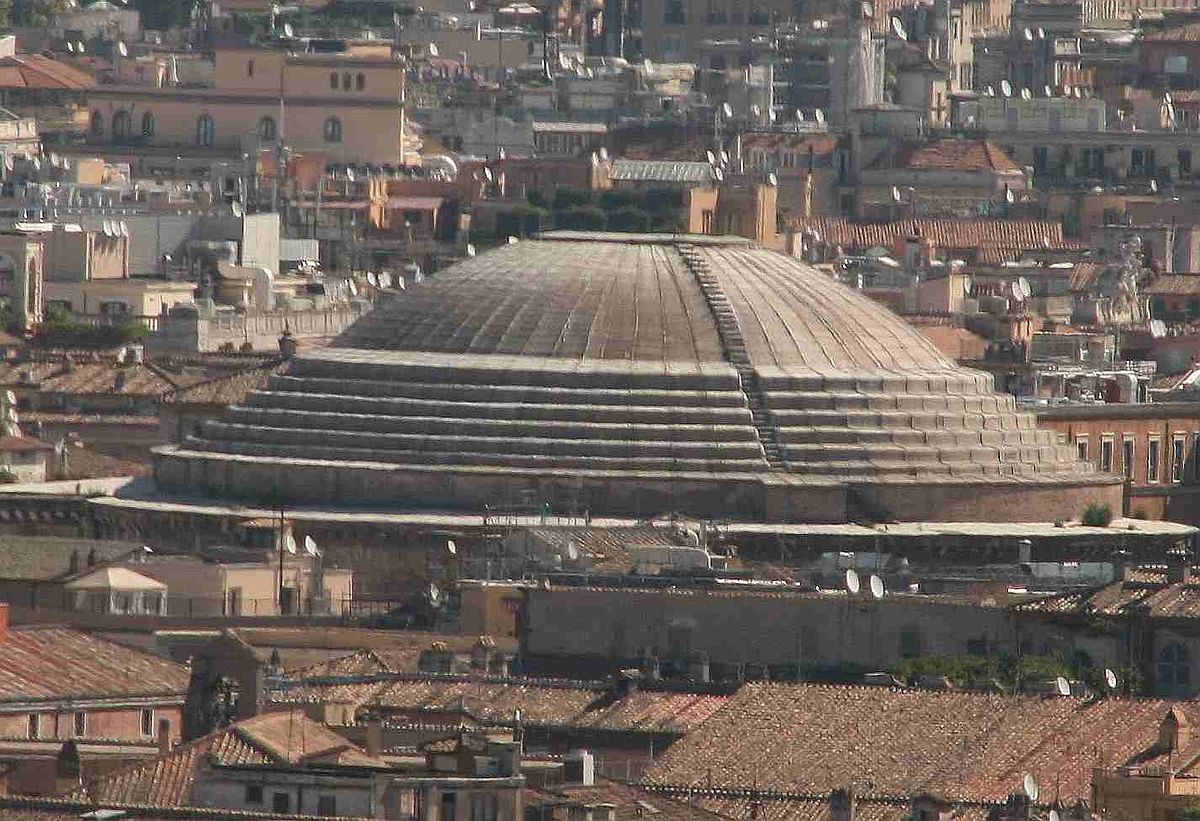

Architecture also speaks. Gates with paired guardians, passages that narrow by stages, and courts set on axes all mirror the underworld’s sevenfold entry. Visitors to major temples would have felt the pattern in their bodies. Progress requires surrender. Honour flows through clear channels. Power seats itself in a hall and expects reports. Religion is choreography as much as creed.

Erra, war, and the problem of heat

Later Babylonian poetry gives Nergal another face. As Erra, he grows restless when the world grows soft. He leaves his city and stirs conflict to remind people what courage is for. The poem reads like a meditation on crisis. Too much peace dulls the senses. Too much war burns the garden. A wise ruler, human or divine, knows when to tighten and when to relax. Ereshkigal’s presence tempers Erra’s fire. She anchors him to duty. He gives her reach beyond the walls of Ganzir. Together they keep the balance uneasy but real.

This pairing also helps explain seasonal extremes. When summer presses hard, worshippers might imagine Nergal roving. When the first cool wind arrives, he has returned to his seat. Stories and weather speak to each other. Rituals mark the turn.

Justice, borders, and the dead who will not rest

Not every wrong is settled among the living. Some cases collapse into silence while the guilty thrive. Mesopotamian law codes address this, yet myth goes further. In many tales, the queen of the Great Below receives petitions. The dead can be stirred as witnesses. Nergal, with his soldier’s mind, enforces verdicts. Demons drag offenders by the ankle. Doors that once opened easily now resist. Norms reach into places that kings cannot touch with edicts alone.

There is a social function here. Belief in a firm underworld court supports civic trust. It tells the frightened that grief will be accounted for, even if not this week, even if not in this court. Ereshkigal’s poise and Nergal’s force combine into a promise. The strong hand serves the seated judge.

Why they still matter

Modern readers can find a use for this pair without adopting the old rites. First, they offer a language for crises. Plague and heat still arrive. Borders still need guarding. Grief still clings. Putting names to these pressures can make them bearable. Second, they model a kind of power-sharing. One partner moves, fights, and enforces. The other holds a seat, records, and decides. Healthy systems need both. Third, they show how a culture faced finality. The dead do not return, yet rituals and law can keep the living steady.

Writers return to them for the same reason city priests once did. They frame the hard parts of life without pretending that pain vanishes. The myths never promise rescue from death. They promise order in spite of it. That promise is worth repeating.

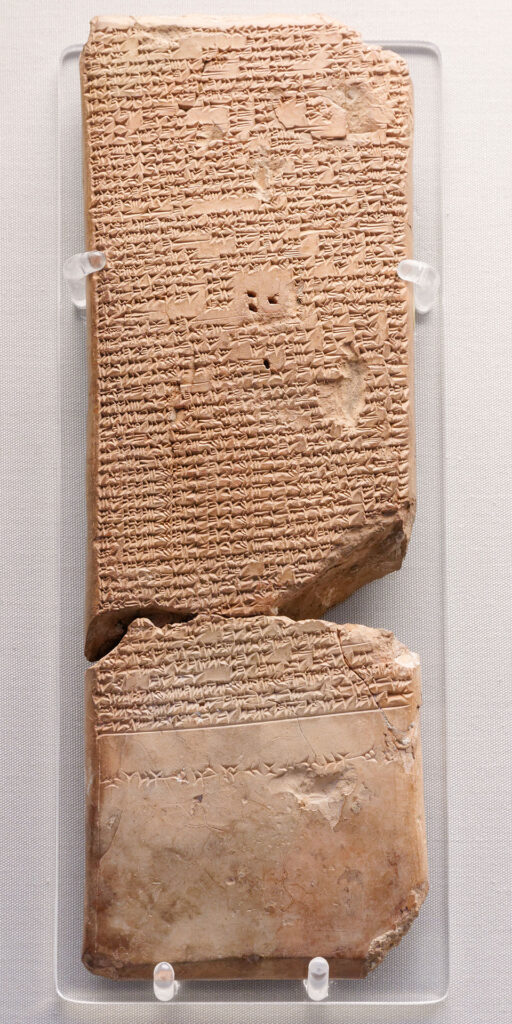

Reading the texts with care

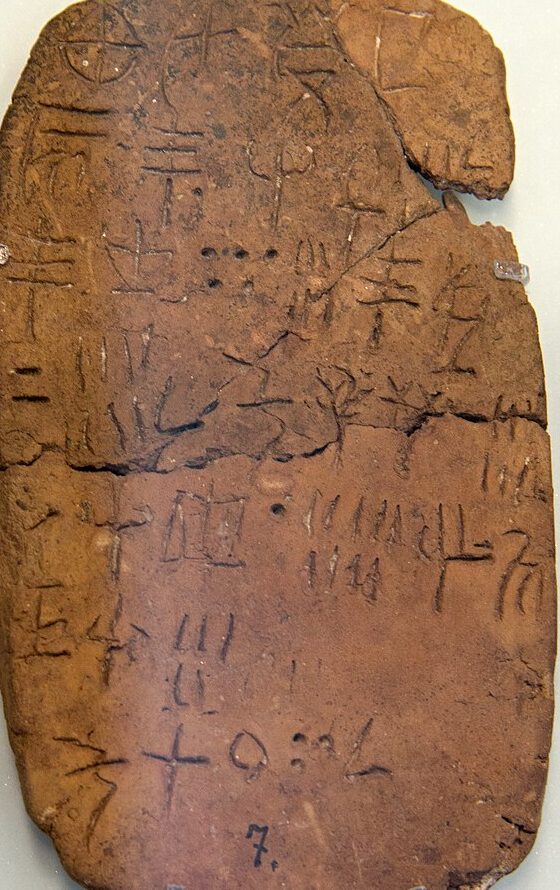

Our knowledge comes from copies, not originals. Scribes in the first millennium loved to collect, revise, and systematise older tales. Variants survive because clay breaks slowly, not because a single edition ruled. That means readers must hold details lightly. In one tablet, Nergal’s pride drives the plot. In another, court politics shape events. Across them all, a pattern holds. The throne of the Great Below bears two names by the end. The order of the dead is shared.

Scholars argue over identifications in art and over lines in broken tablets. This debate is a sign of health, not confusion. It shows that the stories still have bite. New fragments can shift readings; fresh comparisons can change tone. The core remains. Ereshkigal reigns. Nergal accepts a place. Gates open and close in sequence. The living make offerings and wait for news that the court below is calm.

From temple to household

Grand myths find their way into kitchens. A family pours a small libation and speaks a name. A sick child receives a whispered prayer as a fever breaks. A merchant leaving a city gate touches a charm stamped with a lion and a mace. These gestures do not require the full tale, yet they live inside it. People borrow the parts they need. A ruler demands justice and calls on Nergal to act. A widow hopes for fair hearing and names Ereshkigal under her breath. Myth becomes civic habit and private hope at once.

That is how stories endure. They move where people move. They shrink for the pocket and expand for the festival. They carry enough structure to be recognisable, yet they flex to fit a day’s demands.

A final thread to hold

Think of the marriage as a hinge. On one side sits raw force: heat, violence, and the terror of disease. On the other sits rule, record, and the patience of a queen who never hurries. The hinge lets the door swing without tearing from the frame. When it sticks, everyone hears it. When it moves, the house works. Nergal and Ereshkigal are that mechanism for a civilisation that prized order and feared drought in equal measure.

These gods do not ask for love. They ask for acknowledgement. Respect the gate. Honour the court. Accept that some parts of life will always sting. Then keep going. In the end, that may be the most practical theology a river culture ever wrote.