The Greek Day Begins at Sunrise

Roosters along the Aegean coast crowed long before the sun breached marble temple roofs. A free male citizen might roll off a straw mattress by first light, splash rain‑catch water on his face, and offer a pinch of barley to Hestia’s hearth fire. Women were already awake, grinding grain on quern stones that left tell‑tale calluses on the first two fingers—marks so common archaeologists call them “the Greek manicure.” Children gulped diluted wine, thought safer than cistern water, and munched yesterday’s bread soaked in olive oil before heading to lessons or errands.

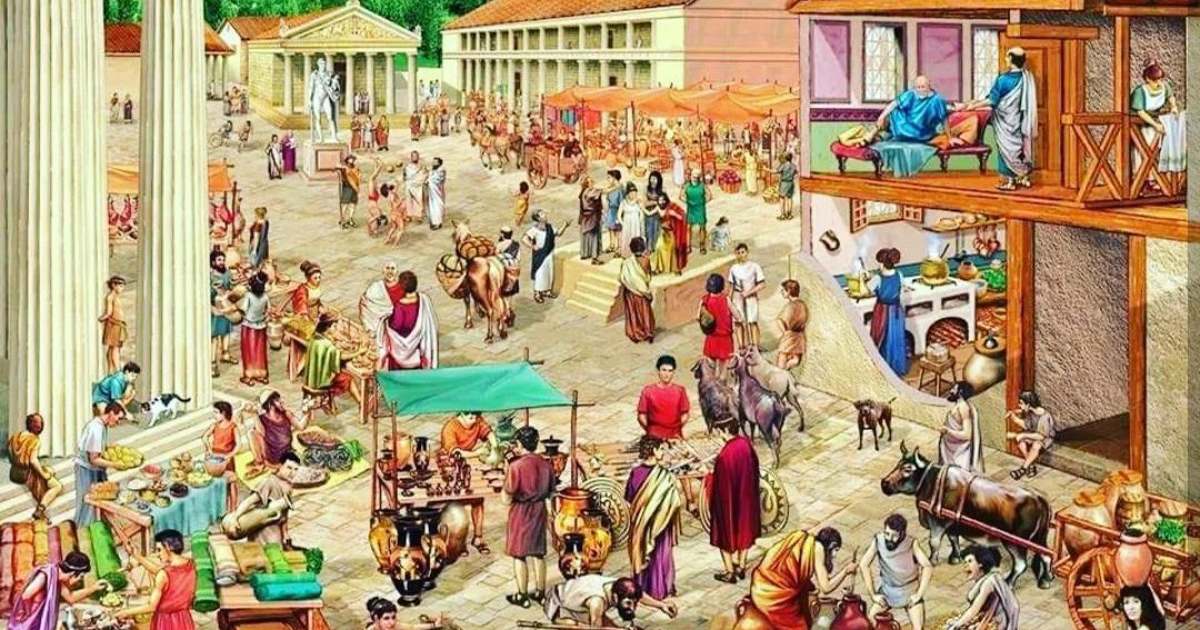

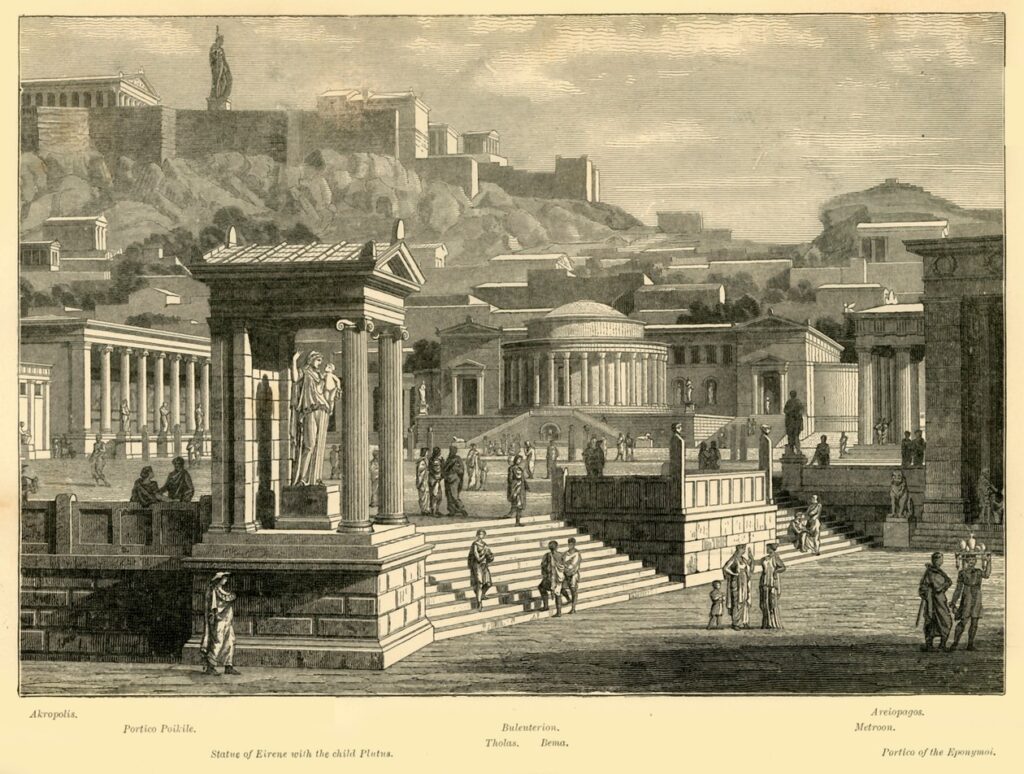

Work and the Pulse of the Agora

The agora, Athens’ open marketplace, was office, court, and newsfeed rolled into one. Bronze founders clanged hammers near stands selling figs from Euboea, Chian wine, and Egyptian papyrus. Professional scribes rented wooden booths where illiterate farmers could dictate legal complaints for a few obols. Barber stalls doubled as gossip hubs; a fresh shave included updates on Macedonian maneuvers or the latest comedy at the Dionysia festival. By mid‑morning the sun sheeted white heat off limestone colonnades, and shop awnings snapped in the sea breeze like sails.

Inside the Oikos: Women, Children, and Domestic Power

Despite public statues of spear‑wielding heroes, daily stability depended on the household run by women. Married at fourteen in arranged matches, Athenian wives supervised slaves, wove linen, and kept ledgers of oil and grain—skills praised in Hesiod almost as highly as chastity. Spartan women, by contrast, owned land in their own names and exercised in public gymnasia; Plutarch quipped that a Spartan girl’s tunic “showed the thighs and never the mind was idle.” Both cities measured female virtue by bearing strong sons, yet funerary stelae reveal mothers commemorated for wisdom and tender speech as often as for fertility.

Food, Flavour, and the Noon Respite

Most Greeks ate two main meals. Ariston (late morning) featured barley bread, goat cheese, olives, and—for the prosperous—salted fish from Black Sea fleets. Protein sometimes arrived via pigeons trapped on rooftop coops or lentils thickened with thyme. Sweeteners came from grapes boiled into petimezi syrup; beekeeping remained a luxury outside Attica’s thyme‑rich hills. Wine, cut with water in ratios debated by philosophers, acted as calorie booster and disinfectant. Mid‑day heat drove even stonemasons indoors; siesta wasn’t laziness but adaptation to Mediterranean climate.

The Symposium: Night‑School for Elites

After dusk, wealthy men reclined on couches in the andron—a male‑only dining room whose pebble mosaics often depicted Dionysus. The host’s slave boy mixed kraters of wine three parts water to one part Lesbos red; stronger ratios risked social censure as akrasia (loss of self‑control). Between toasts, aulos players piped double‑reed melodies while guests tossed quips in hexameter or played kottabos, flinging wine lees at bronze targets. Philosophical disputes sparked productively: Plato sets his Symposium amid banter on love, while Xenophon’s memoir celebrates the hired juggler whose sword dance quieted political squabbles.

Public Faith and Private Superstition

Religion saturated the calendar—over 120 festival days in Athens alone. Farmers hauled first fruits to Demeter at Eleusis; sailors promised a goat to Poseidon for safe return; mothers laced toddlers’ wrists with knotted wool to ward off phthonos, the evil eye. Sacrifice was transaction, not blind devotion: gods received smoke and song, humans expected crop fertility or victory. Oracle networks—Delphi, Dodona, and lesser sanctuaries in cave groves—functioned like interstate data centers mediating policy. Even empirical thinkers hedged bets: before departing to Syracuse, the engineer Archimedes reportedly burned incense on Artemis’s altar “just in case.”

Education and Paideia

Formal schooling mixed literacy with gymnastics, echoing the ideal of kalokagathia—beauty united with goodness. Boys learned the alphabet by scratching wax tablets, recited Homer until hexameters haunted dreams, and studied lyre to soften warrior hearts. Tuition cost two drachmas a month, affordable for artisans but steep for rural families. Girls in Athens seldom saw such classrooms, yet papyri from Hellenistic Egypt include handwriting drills by female students, hinting at wider literacy under later successor kingdoms.

Gymnasium, Training Ground, Dating App

Nude exercise in the palaestra glazed bodies with olive oil and dust to prevent sunburn. Wrestling matches doubled as social networking; older patrons courted youths through gifts of hares or cockleshells, a practice legislated but culturally nuanced. Sprinters measured time in “shield lengths,” and javelin throwers attached leather straps (ankyle) to extend spin. Military drill was never far: hoplites drilled the pyknosis maneuver—tightening ranks—until shields clanged like one bronze wall.

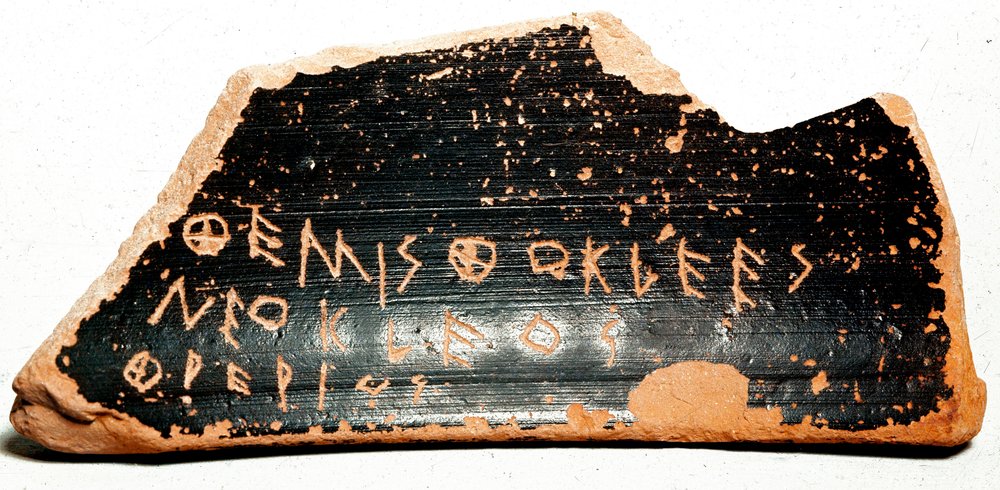

Enslaved Majority: The Backbone and Burden

Freedom in Greek poleis rested on widespread unfreedom. By some counts, slaves comprised one‑third of Attica’s populace. Sources divide them into household servants, skilled miners, and untaxed “chattel for rent.” At Laurion silver mines, shackled workers died from lead poisoning by age twenty. Yet legal records show slaves buying freedom for a talent or less, adopting their former master’s patronym, and sometimes accumulating property.

Sparta’s helots occupied a more terrifying niche: state‑owned serfs bound to Messenian soil. Each autumn ephors declared ritual war on helots, legalising their killing by stealth squads of teenage krypteia. Classical writers depict the helot as lazy or treacherous—a propaganda mirror deflecting Spartan dependence. When Theban general Epaminondas liberated Messenia in 369 BCE, freed helots reportedly wept and sang hymns to new‑built city walls.

Entertainment, from Tragedy Masks to Betting on Quails

The theatre season at Athens reached football‑final fervor. Entire demes marched with picnic baskets to the south slope of the Acropolis, where stone benches could seat 14 000. Sponsors (choregoi) funded choruses to win civic glory; losers paid fines for poor staging. Even between festivals, Athenians chased thrill in smaller venues: cockfighting rings under the Long Walls and quail fights judged by piercing cries. Dice carved from knucklebones clattered in taverns despite sumptuary laws.

The Household Gods Go to Bed

As stars glimmered over Mount Hymettus, families gathered for a final nibble—figs and honeyed cheese curds—then snuffed tallow lamps with fig‑leaf snuffers. Slaves locked courtyard doors and slept on woven mats outside master bedrooms. Citizens reviewed household accounts on wax tablets by lamplight; women spun wool by drop spindle until wrists cramped. Across the gulf, a Spartan patrol whispered pass‑phrases, ensuring no helot fires burned too bright after curfew.

Echoes in the Modern Kitchen and Parliament

- Ritualised drinking culture: Today’s wine tastings and toasts trace lineage to the symposium’s measured pours and philosophical games.

- Household data: Budgeting apps do digitally what Greek wives did with pebble tallies—prove that bread, oil, and rent balance.

- Slavery’s shadow: Global supply chains still hinge on unseen labour; Laurion’s tunnels warn that prosperity can blind citizens to buried suffering.

- Public space matters: Whether town hall or social media feed, the agora’s lesson endures: democracy needs somewhere noisy to live.