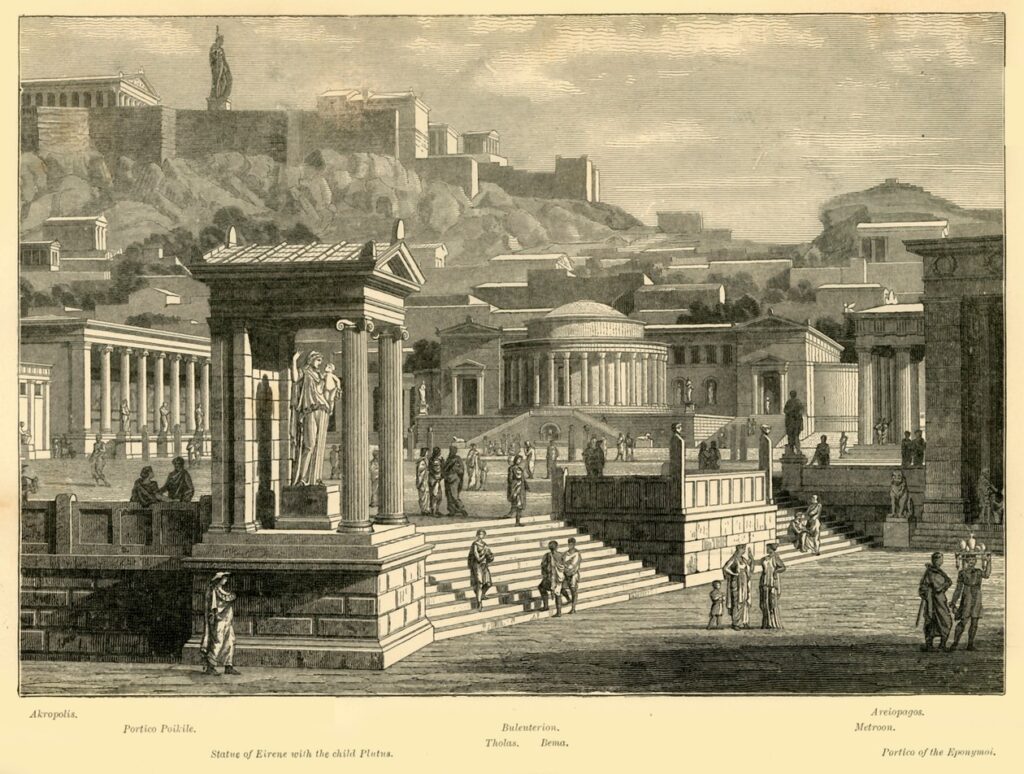

Ancient Infrastructure held the ancient world together. Roads, canals, ports, drains, dams, milestones, and lighthouses turned distance into something manageable. Grain could reach cities before it spoiled. Timber and stone met where builders needed them. Priests, envoys, and artisans travelled safely enough to trust their journeys. In short, public works made politics possible. This pillar guide sets out how those systems worked, how people maintained them, and why that still matters.

What ancient infrastructure did, and why it mattered

Infrastructure is more than stone and earth. It is a promise that today’s departure leads to tomorrow’s arrival. In the ancient world that promise rested on steady maintenance, fair tolls, predictable waystations, and shared standards. Because of that, Ancient Infrastructure shaped taxation, diplomacy, health, famine relief, and even belief. A road patrol discouraged raiders; a dredged harbour cut prices; a repaired dam saved a harvest. These small, regular acts had continental effects.

Water first: canals, levees, and pipes

Water management sat at the core of urban life. It irrigated fields, fed workshops, and cooled crowded neighbourhoods. With it came stability; without it, even strong states failed. The clever part is not only scale but control. Engineers learned to steer flow gently, split rivers safely, and store rain without rot. These choices reduced flood shocks and smoothed out lean years.

Assyrian stonework: a royal aqueduct in the steppe

When Assyrian kings diverted rivers to feed gardens and fields, they built with purpose. The Jerwan aqueduct demonstrates dressed stone, measured gradients, and inscriptions that tie engineering to royal legitimacy. It also shows something practical: once a canal crosses rough ground, you either cut a trench or raise a bridge. Here, the builders raised stone and set a precedent for later aqueducts.

Monsoon logic: splitting a river without a dam

In Sichuan, engineers learned to work with flow. The Dujiangyan scheme splits the Min River into channels that change duty with the season. Rather than a tall dam, it uses shaped banks, calibrated cuts, and a weir to share power with the river. That approach made repairs simpler and reduced catastrophic failure.

Rock-cut intelligence in the desert

Petra’s channels show learning by habit. Carvers kept the flow low, protected from sun and grit, and built settling tanks to trap silt. Clay pipes, stone lids, and overflow slots reveal steady maintenance. The point was not grandeur; the point was reliability. That is the quiet signature of effective Ancient Infrastructure.

Roads and relays: speed by slices

Overland movement gained speed not only from paving but from organisation. Relay stages trimmed risk; milestones enforced accountability. A rider with a fresh horse at each stop beats a lone courier every time. Traders copied the method with pack animals and sealed bales, moving goods in segments rather than gambling on one anxious dash.

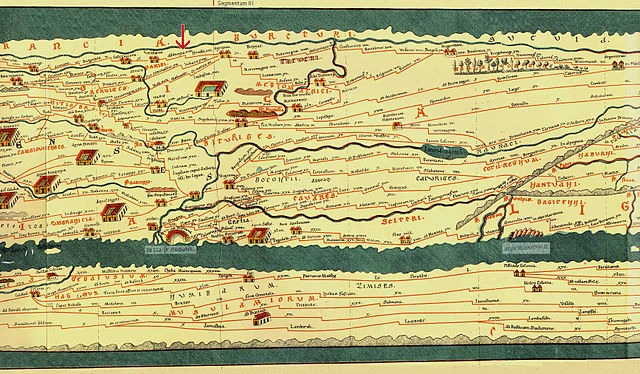

Across the Balkans in measured steps

Roman road-builders understood water as well as stone. Cambered surfaces shed rain; ditches carried it away. In cuttings, retaining walls held slopes in place. At fords and bridges, traffic narrowed by design so loads could be checked and tolls taken. Regularity mattered more than raw speed, because predictability sets prices and schedules.

Ports and dockyards: where inland meets tide

Coastal cities live or die by their edges. A useful port needs depth, shelter, and a stable working shore. It also needs storage, repair space, and honest scales. Silt pushes back constantly, so dredging and re-cutting channels become routine. The quieter the dockyard stories, the better the port is doing.

Wet basins and silt traps in the Indus world

At Lothal, brick courses, sluices, and apron stones suggest careful water control. A basin behind a gate would have softened tidal shock and caught silt where labourers could shovel it out easily. Adjacent platforms likely held scales and storage jars. Even without a single surviving hull, the layout reads like a manual.

Sanitation and flood control: the city beneath the city

People notice walls and theatres. They forget drains until a storm arrives. Yet the unseen city keeps the seen one alive. Covered channels carry waste away from wells; culverts lift streets above mud; embankments hold rivers in their beds long enough for markets to open on time. The best praise for a drain is silence.

Shaping a river city’s underside

Rome grew around a managed watershed. Drains linked hillsides, squares, and alleys to the Tiber. Embankments raised quays out of flood reach, while stairways kept access for water sellers and boatmen. Stone covers made repairs quick and cheap because crews could lift only the sections they needed.

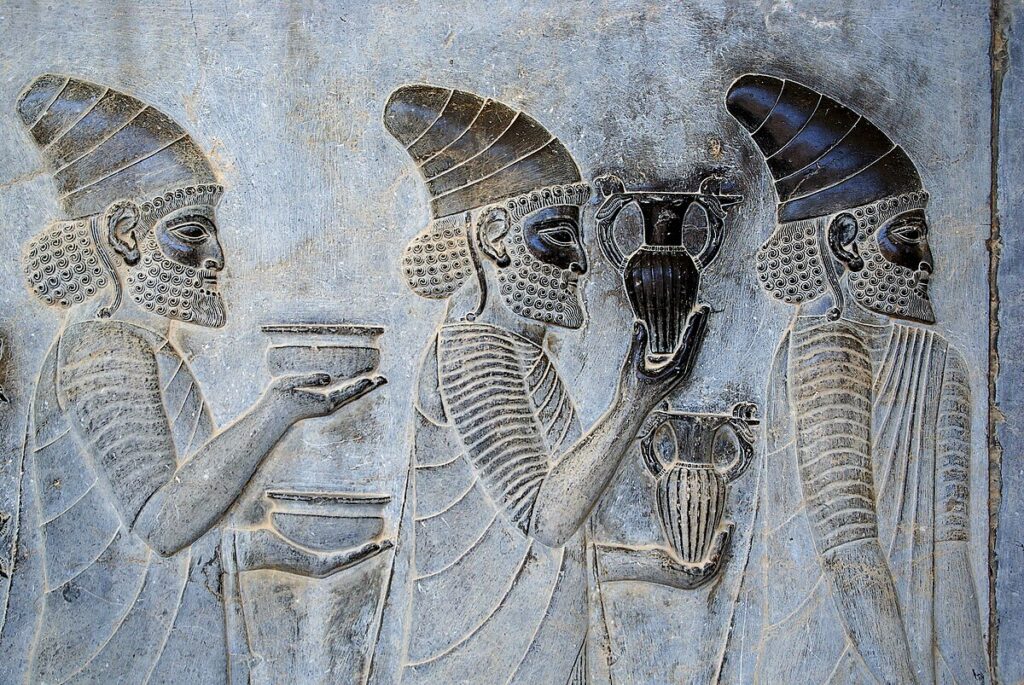

Standards: weights, measures, and time

Trade collapses if buyers and sellers cannot agree what a “pound” is. That is why so many ruins yield nested weights, stamped measures, and calendars carved on temple walls. Standards anchor trust. A posted measure warns a cheating shopkeeper; an official weight lets a caravan’s partners settle accounts without quarrel. Timekeeping matters too. When winds and river heights follow patterns, a shipping calendar is as valuable as a new road.

Project management before the clipboard

Large works rarely relied on brute force alone. Overseers scheduled shifts, staged materials, and stockpiled tools near the site. Corvée labour mixed with paid crews, while priests handled offerings for safety and luck. Contracts fixed deadlines against seasons; penalties kicked in if a bridge missed its low-water window. A modern project manager would recognise the meeting notes: sequence, risk, budget, and finish-line checks.

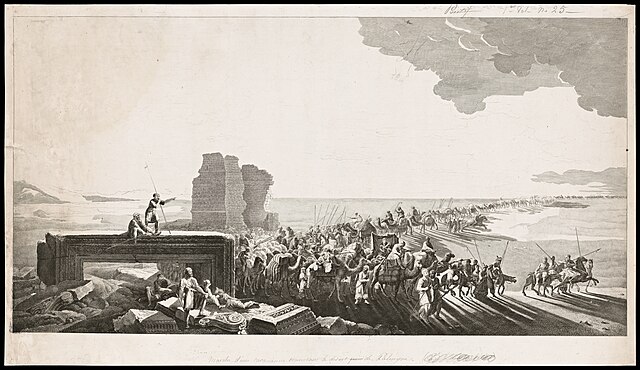

Security that does not strangle movement

Bandits and pirates were a nuisance and sometimes a disaster. However, smothering travel with guards could raise costs past the point of usefulness. States aimed for balance. Convoys grouped slow carts; patrols swept trouble spots; beacons sent warnings along ridges. Insurance through partnerships spread losses. Most of the time, that was enough to keep the route alive without scaring merchants off the road.

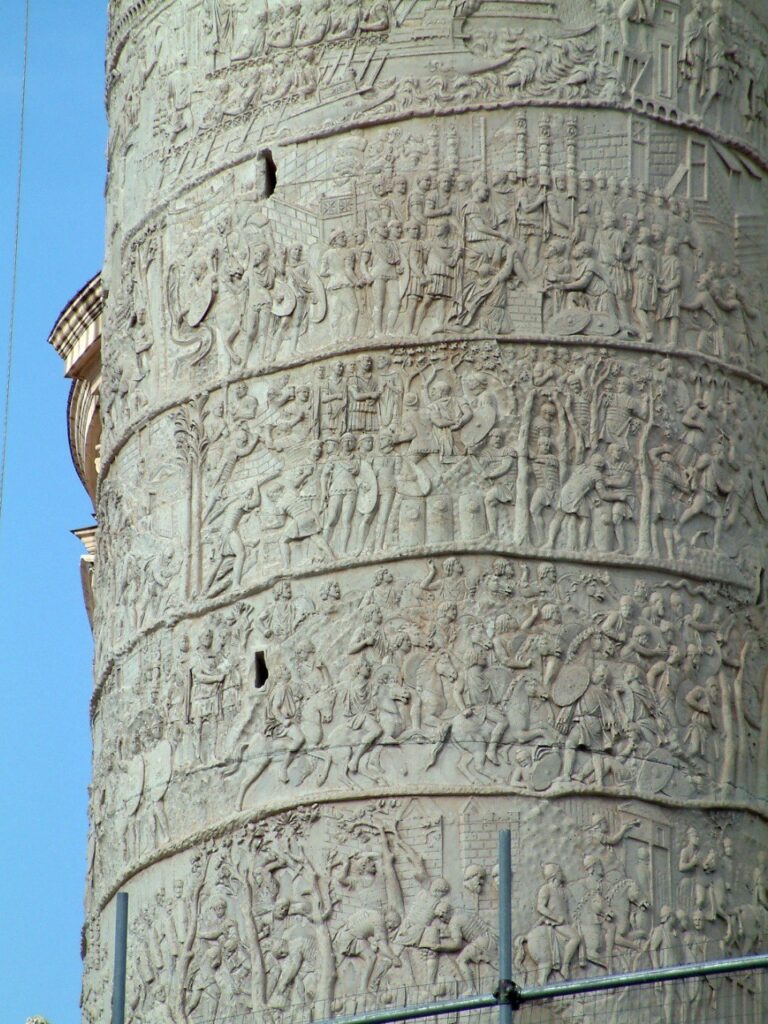

Repair beats reinvention

Great works look glamorous when new, but maintenance makes them valuable. Ditches silt up; pavements heave in heat and frost; timber worm-eats; mortar leaches. Skilled crews knew how to spot bulges, undercut cracks, and clogged joints. Budgets set aside for upkeep paid back every season in fewer collapses and faster traffic. The longest-lived elements of Ancient Infrastructure are the ones that attracted routine, not trumpets.

Reading ruins as checklists

When you walk an ancient road, look not only at paving. Find the drainage cut, the curb height, and the culvert mouth. In a harbour, hunt the silt trap, the mooring slots, and the space where a crane might stand. In a canal, measure how the lining changes where soil shifts. These clues tell you how builders solved ordinary problems. They also tell you how different regions taught one another.

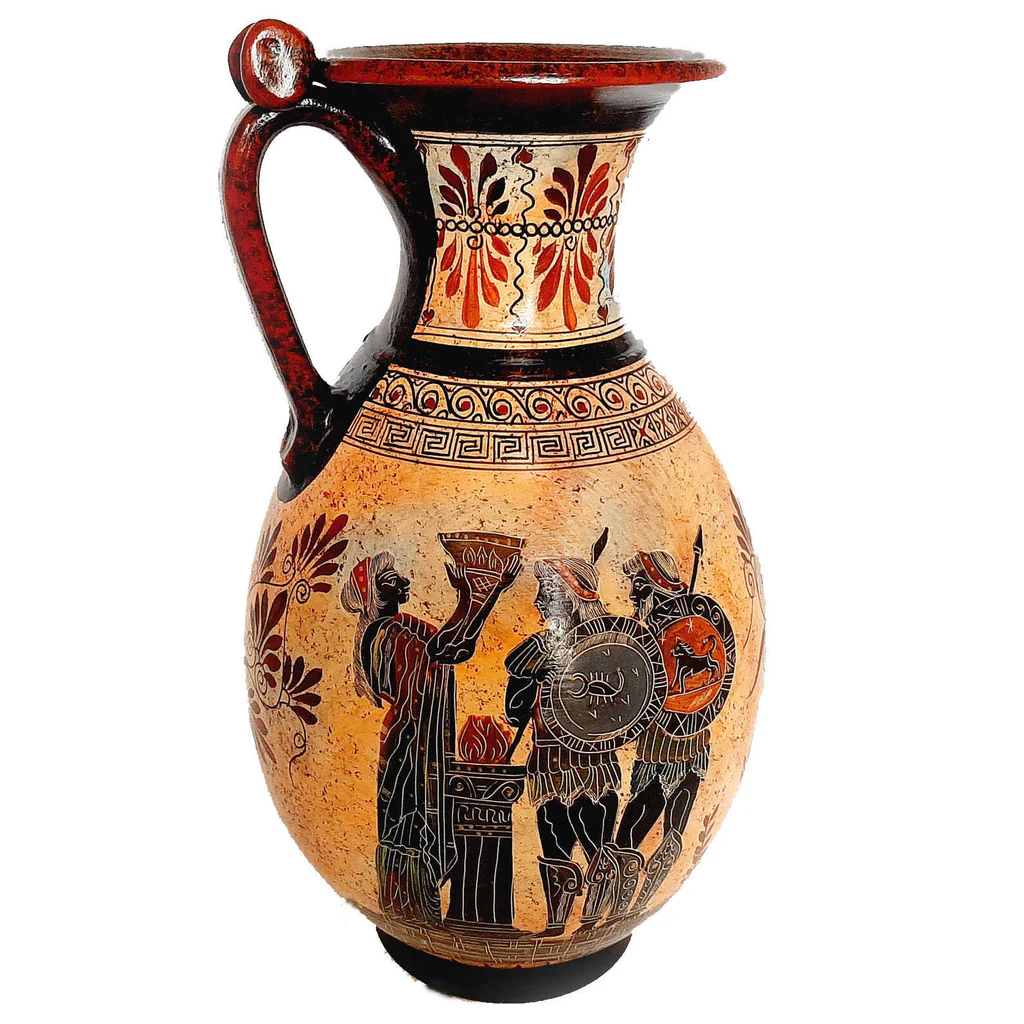

Cross-pollination without conquest

Engineering travelled with people who made their living by movement. A mason who learned to raise an arch taught a neighbour to do the same. A pilot with a reliable wind calendar taught a younger crew when to risk a crossing. Techniques jumped across language lines faster than law did. Ports and caravan cities were classrooms disguised as markets.

Costs, tolls, and fairness

Tolls and customs financed repairs, patrols, and lights. High rates killed routes; low rates starved maintenance. Successful governors published tables, kept inspectors honest enough, and punished a few public cheats to remind everyone else. Markets responded quickly. A fairly priced pass with clean wells drew caravans away from a rougher road even if it was shorter.

Failures that taught lessons

Not every scheme worked. Dams failed when silt choked spillways. Roads slid when builders undercut slopes. Drains backed up because someone paved over an access hatch. Each failure left traces. Later crews widened spillways, terraced fragile banks, and marked covers more clearly. The archaeological record holds as many corrections as first attempts, which is exactly what you would expect from living systems.

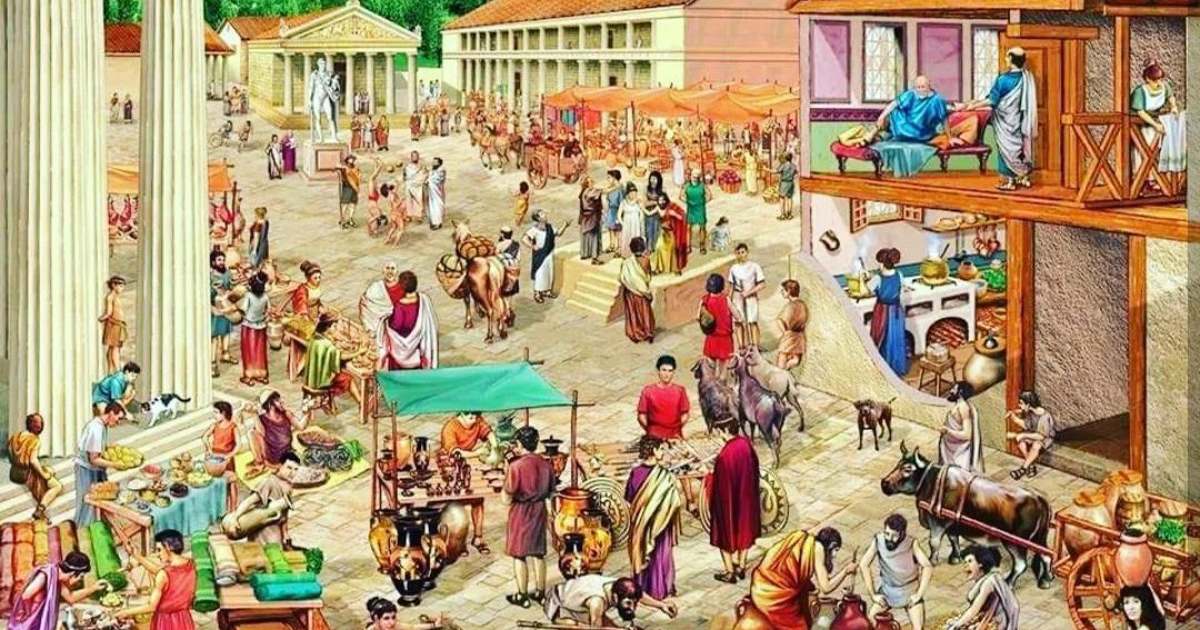

Everyday users, not just royal sponsors

Inscriptions love kings. Ruins show the hands of many more people: the woman who swept a shop threshold to keep grit out of scales; the muleteer who propped a wheel track with a stone; the stevedore who chalked a tally on a jar; the mason who cut a small drain to stop puddling near a doorway. These are the acts that make grand designs practical. Without them, bridges stand over empty roads.

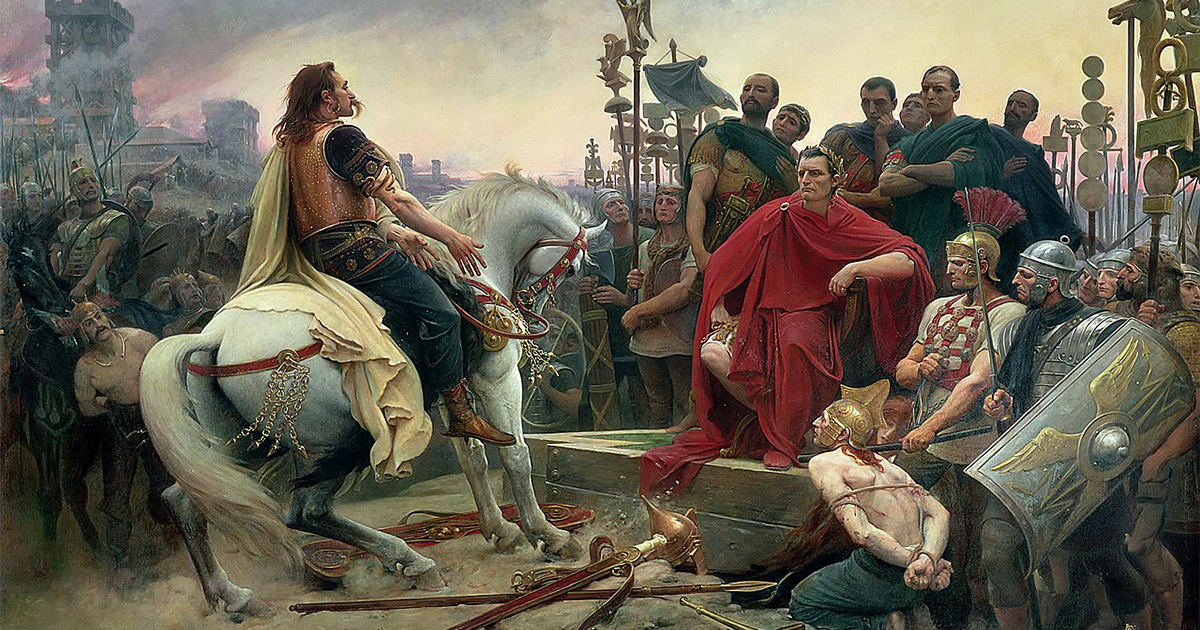

Rituals and rules at thresholds

Gates, bridges, and harbours attract ceremony because they sit where obligations change. A traveller leaves one jurisdiction and enters another. Priests bless crossings; officials stamp papers; toll-keepers tally bales. The ritual comfort helps traffic obey rules without constant force. Public works do political work quietly at every threshold.

How climate and geology shape design

Design follows the ground. In floodplains, engineers emphasised levees and raised causeways. In karst country, sinkholes demanded deep foundations and flexible routes. Along windy coasts, breakwaters took the brunt so inner basins stayed calm. Mountain passes asked for hairpins, stone revetments, and winter closure plans. There is no single ancient way to build; there is a library of local answers arranged by rock, wind, and water.

Materials and their limits

Stone endures but cracks; timber flexes but rots; brick balances cost and control. Lime mortar breathes and heals hairlines; pozzolanic additives set under water and resist the sea. Builders picked what the landscape offered and the budget allowed. You can often see the economy in the joints. Tight fits and even courses signal plenty of labour and time; rougher work points to haste or poverty.

Infrastructure and power

Order grows where movement is predictable. Governors gain reach if messages arrive fast; merchants invest if theft is rare; farmers plant if water arrives when promised. That is why proclamations about roads, canals, and ports so often sit beside tax reforms and legal codes. Ancient Infrastructure turned claims into realities. A ruler who neglected it ruled on paper only.

Why this still matters

Modern networks look different, but the logic holds. Fair standards make strangers legible. Regular maintenance beats grand openings. Projects fail when security strangles trade or when prices ignore season and ground. The ancient record is not a museum of marvels; it is a notebook of workable habits. When we study it closely, we inherit a toolkit: measure honestly, publish rules, plan for repair, and keep the water moving.