Tenea has always felt like a rumour that refused to die. Ancient writers spoke of it with the ease of people pointing to a place on a map, yet for generations no one could put a spade in the ground and say, “Here.” The story runs that Trojan captives, spared after the fall of their city, were allowed to settle on Corinthian soil and build a new life. It is a tale of people carrying memory across the sea and planting it in foreign earth. For a long time that was all we had—fine words, a name, and a landscape that kept its secrets.

The name itself nods across the Aegean. Tenedos, the small island off the Troad, offered the founders a link to home; Tenea echoes it like an aftersound. Over time, that echo mixed with the rhythms of the Peloponnese. The settlement joined the orbit of Corinth while keeping a personality of its own, much like a younger sibling who shares a roof but insists on different tastes and friends.

A Refuge with Trojan Roots

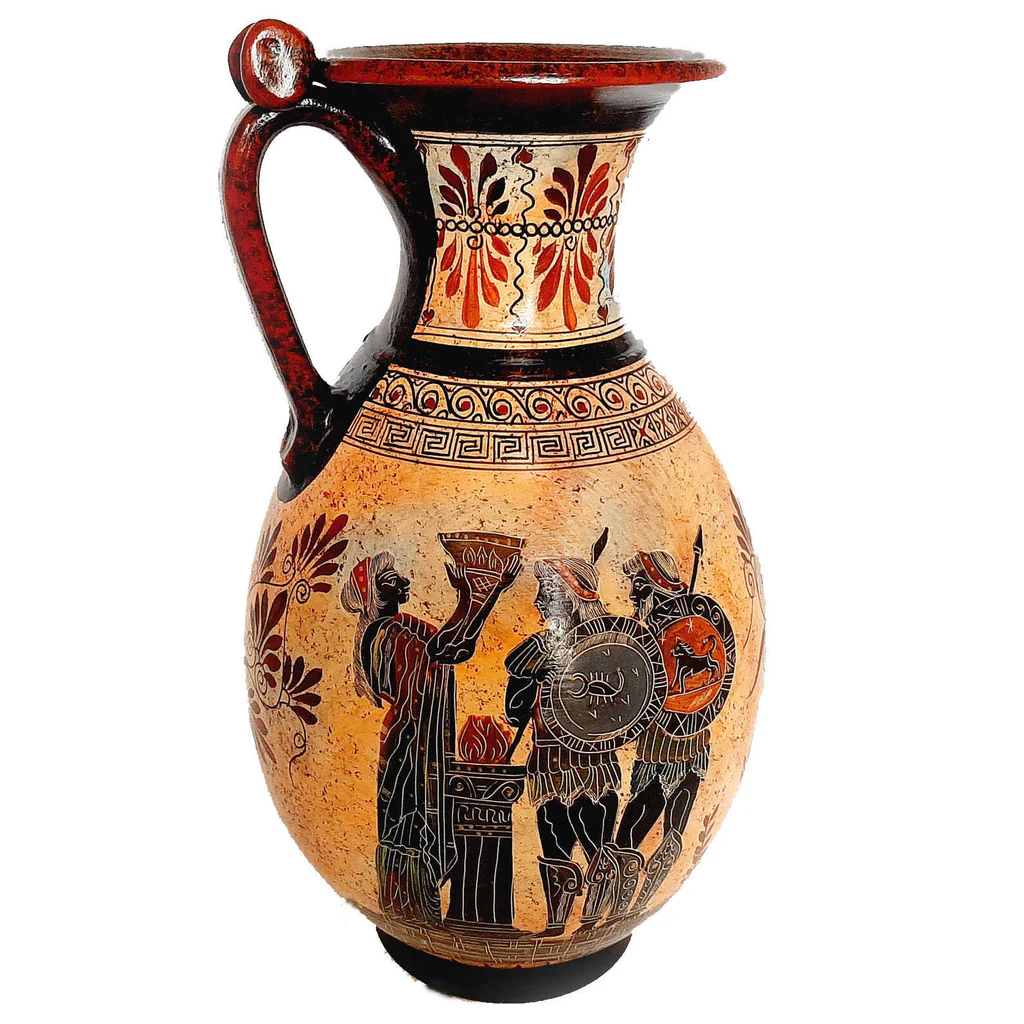

Strip away the poetry of the epic cycle and you still find a world reshaped by movement—families displaced, crafts carried in memory, gods given new addresses. The people who made Tenea did not arrive empty-handed. They brought skills in masonry, metalwork and trading; they brought a way of speaking and a way of honouring the divine; they brought the stubborn wish to belong somewhere again. Out of those ingredients a community formed, and then a city, and eventually a reputation.

Tenea’s fortunes rose early. It sat in a good neighbourhood: close enough to Corinth to tap into its commerce, and near routes that pushed westward towards the Ionian and south towards the Argolid. Ancient tradition even credits Tenea with supplying people for the expedition that founded Syracuse in the eighth century BC under the Corinthian Archias. Whether each detail holds up under strict scrutiny matters less than the theme: Tenea looked outward. It sent young men and ambitions abroad; it was not a backwater watching the world pass by.

An Unusual Friendship with Rome

Centuries later, when Roman armies reduced Corinth to ashes in 146 BC, Tenea appears to have avoided the same fate. Why a small city should be spared while its famous neighbour burned has long intrigued historians. A neat explanation is available: the Romans traced their mythical ancestry to Aeneas, a Trojan survivor. Sympathy for a city with Trojan roots would have been politically convenient and culturally pleasing. It may also be that Tenea had simply learned the art of timing—knowing when to step aside, whom to flatter, and how to weather a storm by keeping one’s head down.

Whatever the reason, survival altered the city’s trajectory. Tenea adapted to Roman administration, minted and handled coins with imperial faces, and fitted itself into a new world order. In the layers of soil left to us, the Roman period supplies pottery, glassware and architectural fittings that tell of households managing well enough under distant rule.

A Statue Emerges from the Soil

Long before anyone could point to streets or house-walls, one object fired the imagination. In 1846, farmers near the present-day village of Chiliomodi pulled from the ground a marble youth—the piece now known as the Kouros of Tenea. The statue’s proportions and calm, faint smile belong to the sixth century BC, that moment when Greek sculptors learned to coax lifelike presence from stone. If a city could afford such work, someone there had money and taste. The kouros travelled north and today stands in Munich, but its very existence left a breadcrumb trail: there was something here worth the attention of great sculptors.

Systematic Excavation Begins

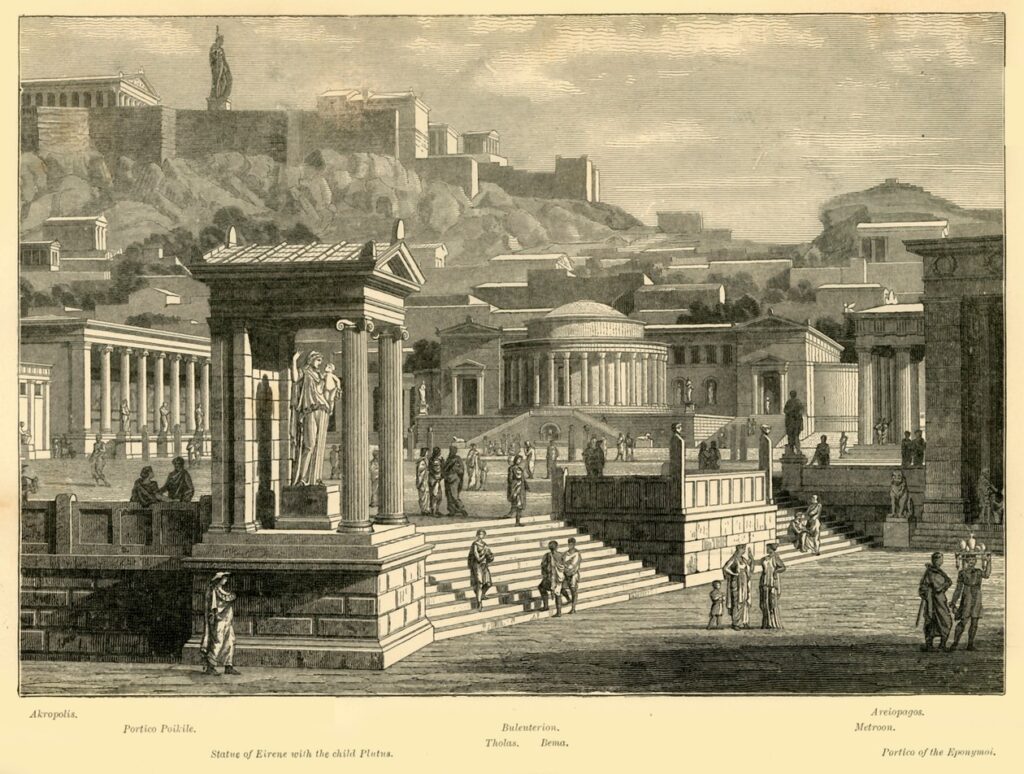

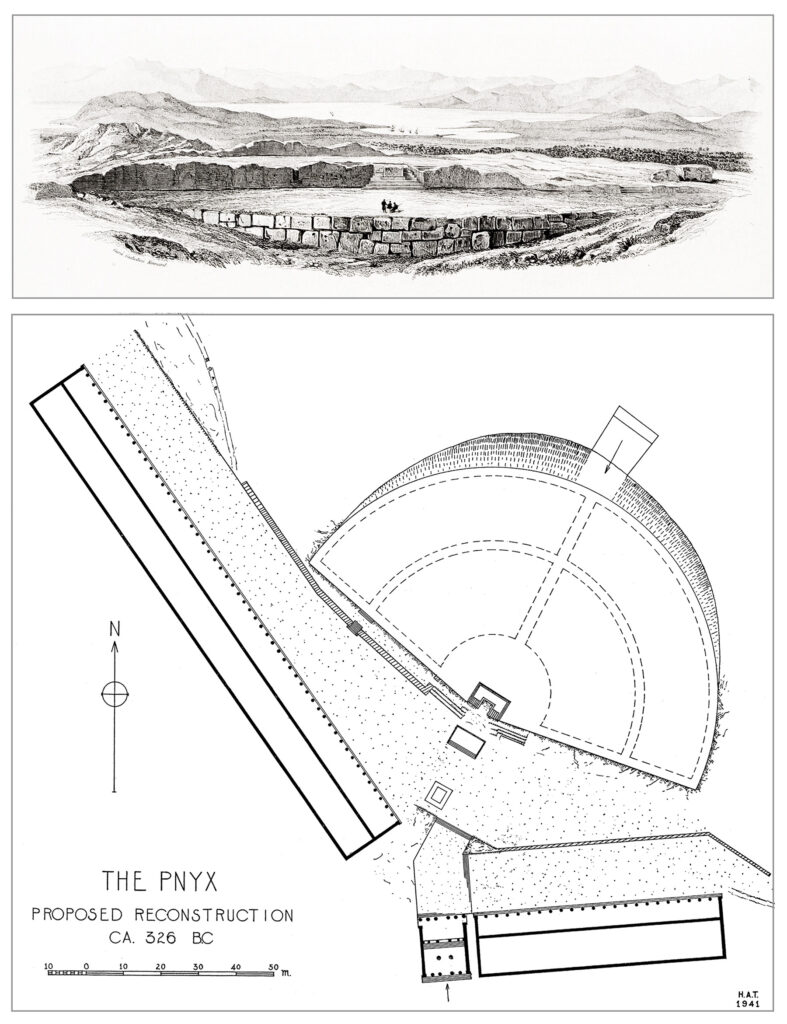

Rumour only gets you so far. What finally changed the conversation was steady, careful archaeology. In recent decades, teams directed by Dr Elena Korka mapped the ground around Chiliomodi, opened trenches and followed walls. Out came domestic floors stitched together with pebbles, the lines of streets with drains set along their edges, and courtyards where broken amphorae piled up in the corners. These are not the theatrical finds that dominate front pages; they are the stubborn facts of urban life. A street, a drain, a threshold: put them in sequence and a neighbourhood appears.

The city’s cupboards were stocked from far afield. Sherds of fine tableware point to trade links across the Aegean; coarse cooking pots speak about taste closer to home—stews simmered slowly, bread baked daily, wine decanted from heavy jars. Coins slipped from fingers and turned up again with the spade, marked with designs that travelled from other poleis. Even fragments of glass—the luxury plastic of the ancient world—show that Tenea kept an eye on style as well as function.

Daily Life in Ancient Tenea

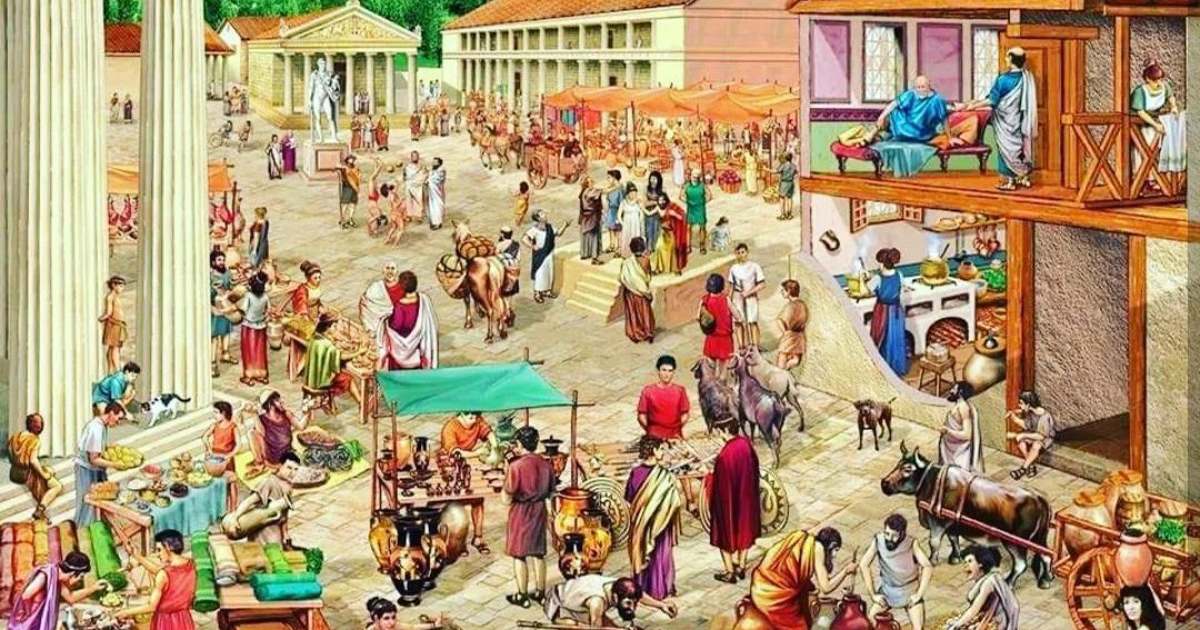

Picture the place on a market day. Farmers walk in from the olive groves with baskets of fruit and jars of oil. A potter leans out of a workshop doorway to check the kiln’s heat. Children weave through the crowd, collecting gossip and pebbles with the same enthusiasm. In the shade of a colonnade a pair of elders argue about a boundary stone, one waving a chipped cup for emphasis. That is the tone set by the archaeology: not palaces and pageants, but the steady thrum of ordinary life carried on for centuries.

Public amenities matched this rhythm. A bathing complex—pipes, basins, the works—shows the city participating in a Mediterranean habit that was part hygiene, part social theatre. You went to the baths to wash, to listen, to be seen. Politics often starts in such places, with wet hair and a towel over the shoulder.

A Monumental Tomb Changes the Picture

Recent seasons produced something grander: a sizeable funerary complex on the city’s edge, laid out in a branching plan that recalls the monumental tombs of northern Greece. Inside lay sarcophagi and stone coffers, grave goods of bronze and glass, pieces of jewellery, and offerings of animal bones placed with ritual care. One ring bears Apollo and a serpent, a pairing that speaks of prophecy and healing. If you needed proof that some families in Tenea could stage their farewells with style, this is it.

The tomb also changes scale. Domestic finds tell you about cooking and shopping; a structure like this speaks to status and memory. It signals that people with means lived here long enough to build for the ages and expected descendants to keep the lamps trimmed. The complex seems to have served more than one generation, perhaps even switching styles as fashion shifted from Hellenistic to Roman. Cities that manage that kind of continuity do so because their institutions—formal or informal—can absorb change without losing themselves.

Religion and Cultural Identity

On the matter of gods, Tenea lived as Greeks did—sacrifices at the right times, processions with music, small offerings tucked into niches at doorways. Yet there is reason to think the city kept a special tenderness for stories of survival. Apollo had obvious appeal: healer, archer, patron of order. A ring from a grave is no catechism, but it gestures towards a household looking to the god for help. We can also imagine household shrines where the founders’ journey from the Troad was recited at festivals, an old tale retold to make sense of the present.

Materially, religion appears in modest ways: a terracotta figurine with the paint just clinging on, a libation channel scored into a stone threshold, ash where a small altar burned a little too hot. Add them up and you hear the background music of devotion that never quite stops.

Why Tenea Captures the Imagination

Part of the appeal is scale. Great capitals dominate textbooks; places like Tenea make history legible. Here you can watch ideas and goods circulating through a middling city that refused to be dull. Another part is the origin story. Refugees do not usually get to write the first draft of history, yet this community took root and, by patience and luck, left us enough to trace its outline. Tenea reminds us that the aftermath of famous events often matters more than the events themselves.

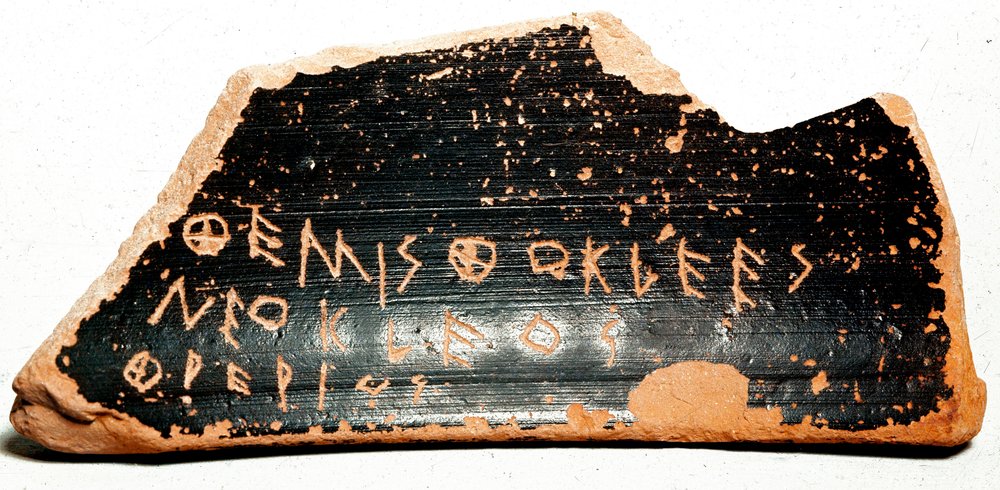

There is also the simple pleasure of seeing text meet earth. A line in Pausanias gains weight when a street line runs exactly where he implies; a stray remark by Strabo feels different when a drain appears to carry water the way he suggests. Not every claim will match neatly, and not every trench gives an answer, but the conversation between word and find is lively here.

Tenea in the Wider Context of Lost Cities

Some ancient places ended with a crash—earthquakes, fires, invasions that leave jagged signatures in the layers. Tenea’s story looks quieter. Populations shift; a road falls out of use; roofs collapse after one too many winters; fields creep back over foundations. Silence gathers. That kind of ending can be harder to notice and, oddly, easier to preserve. Streets sleep under a thin blanket of soil, waiting for a survey team with patience and a trowel sharp enough to shave a hair.

Set alongside other rediscovered towns, Tenea shows how resilient a modest urban centre can be. It thrived by not overreaching, by trading widely, and by investing in the durable pleasures of public life—baths, markets, festivals. Even its fading seems to have been a drawn-out negotiation with time rather than a single catastrophe.

Visiting Tenea Today

The modern visitor meets two landscapes at once. There is the countryside of Corinthia—vineyards running up gentle slopes, dust on the boots by midday, the smell of thyme drawn out by the sun. And there is the grid of the ancient city, faint but real, traced by low walls and the patient pegs of excavation. Chiliomodi serves as a friendly base: coffee on the square, a short drive to the trenches, and museum rooms where glass, jewellery and everyday pottery sit quietly under good light.

It is not a theme park, and that is its charm. You need a little imagination and a willingness to let small things carry weight: a door pivot worn smooth, a shard of a red-figure cup with a musician’s hand still visible, a coin no bigger than a fingernail that passed through a dozen palms before it slipped into the soil. If you stand there long enough, the modern traffic fades and you can hear the faint murmur of a town going about its business.

The Ongoing Story

Archaeology rarely offers a final word. Each season on the site adds a sentence—sometimes a paragraph—to a book still being written. Questions remain on the table. How far did Tenea’s civic institutions differ from those of Corinth? Did its Trojan inheritance shape marriage customs, burial choices or the names parents gave their children? Was there a moment when the city tried to step onto the regional stage and then thought better of it, choosing steadiness over glory?

Answers will come in fragments: a stamped amphora confirming a trade lane; a set of loom weights gathered in one room hinting at cottage industry; a cluster of inscriptions that clear the fog around a local magistrate’s title. That is the pace at which the past usually walks towards us. The lessons are oddly modern. Communities last when they balance memory with change, and when they invest in the humdrum structures—drains, roads, rules—that let ordinary lives proceed with dignity.

Tenea, once a whisper on a page, now has streets you can trace with your finger and houses you can step around. It is not grand in the way of marble-clad capitals, but it is intensely human. A handful of families, the courage to start again, a talent for trade, a readiness to adapt, a stubborn pride in origin: out of that recipe came a city that endured. If you want to meet the ancient world at eye level, not on a pedestal, this is as good a place as any to begin.