Rome did not rise by accident. From the monarchy to the late Empire, each generation layered new tools on top of older foundations: universal military service, roads that pierced every province, written law flexible enough to absorb local custom, and a habit of granting citizenship faster than rivals could grasp the implications. The result was less a patchwork of territories than a network of interlocking systems able to absorb shock after shock yet keep functioning.

Citizen‑Soldiers: Rome’s Original Engine

The earliest legions drew on farmers who served a campaigning season before returning to fields. Victory and plunder justified the sacrifice; popular assemblies even debated whether booty should be sold or allotted. After the Gallic sack of 390 BC exposed flaws in the hoplite phalanx, Rome reorganised into maniples—smaller units that could flex on broken hillsides. Drill manuals carved onto bronze tablets standardised formations, while veterans tutored raw recruits at practice grounds called campi Martii. The payoff came at Sentinum in 295 BC, where manipular spacing allowed reserves to flow through gaps in the line and smash a Samnite wedge. Each battle won by citizen‑soldiers reinforced a bargain: fight for the state, and the state will guard your property and political voice.

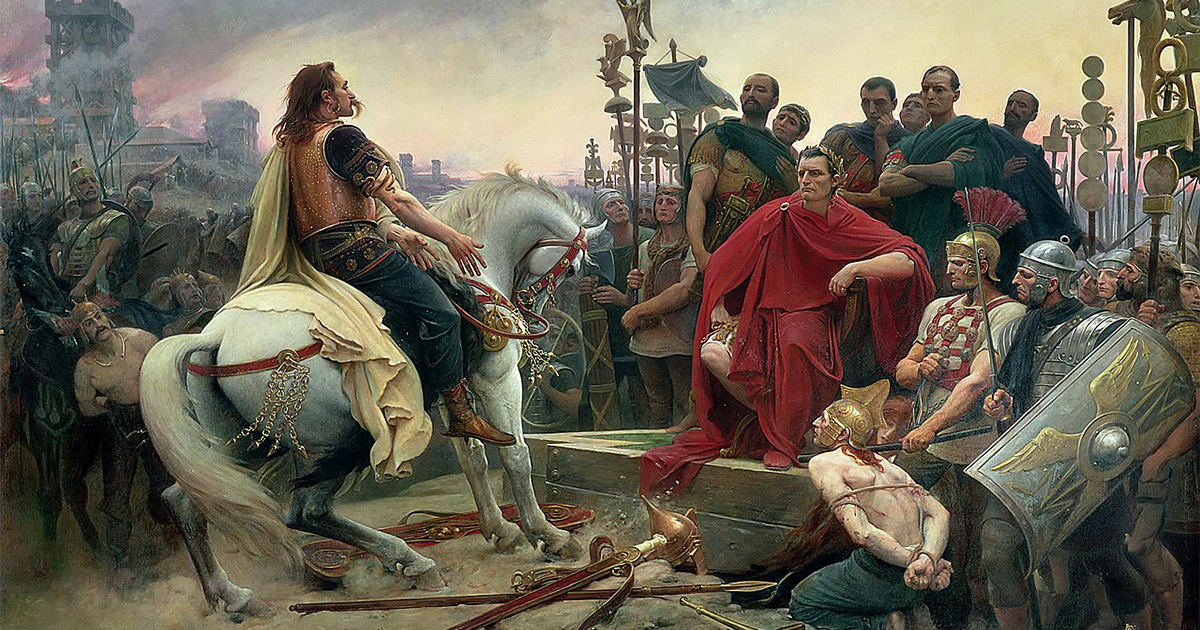

Marius and the Professional Turn

By the second century BC Italy’s smallholders were vanishing, victims of cheap slave grain from Sicily. Gaius Marius solved the manpower crisis by opening enlistment to the capite censi—the head‑count poor who owned no land. In exchange he promised retirement plots in conquered territory. This apparently small reform re‑wired the empire’s sociology: men from Numidia to the Po Valley now viewed military service as a ladder out of poverty. Standard packs, identical shields, and mass‑produced pila replaced the mismatched kit of earlier days. A single legion’s march sounded like a giant metronome, iron hobnails ticking on the road. Discipline fused with opportunity, forging units that could dig ramparts at sunset and assault fortresses at dawn without complaint.

The Road Grid: Concrete Lines of Control

Roman roads began as dirt military spurs but soon carried merchants, couriers, and pilgrims. Surveyors armed with the groma laid out perfectly straight lines until terrain forced a turn. Bridges used volcanic pozzolana cement that hardened under water, allowing spans such as Pont Fabricius to endure twenty centuries. The Via Appia, opened in 312 BC, cut the journey from Rome to Brundisium from three weeks to nine days for a fast courier. Emperor Trajan extended the idea with the Via Traiana, shaving an additional thirty coastal kilometres. By late antiquity the imperial road ledger listed roughly 400 000 kilometres—enough to circle Earth ten times—every one marked by stone milestones noting distance from the Golden Milestone in the Forum.

Aqueducts and Bridges: Water and Movement

Infrastructure served more than armies. The Pont du Gard carried forty million litres of spring water to Nemausus daily, its three‑tiered arches standing 49 metres above the Gardon River. Engineers cut channels with a gradient of barely 34 centimetres per kilometre, ensuring a gentle flow that resisted clogging. In Rome eleven aqueducts poured into cisterns on the Esquiline; gravity and lead pipes fed bath complexes able to wash 6 000 bathers on a summer afternoon. Clean water reduced disease and stoked an urban population that topped one million by the reign of Augustus—an industrial‑scale market that attracted traders from every Mediterranean shore.

Grain, Garum, and the Politics of the Belly

Feeding the capital required logistics worthy of a modern nation‑state. Annual grain demand hovered around 200 000 tonnes. Contracts bound navicularii (ship owners) to deliver Egyptian and North‑African harvests each autumn. In return they gained tax exemptions and the right to wear a gold ring—status markers normally limited to equestrians. At Portus two massive hexagonal basins could anchor 200 vessels. Cargo shifted into river barges, passed through the Porta Trigemina customs gate, and unloaded into the Horrea Galbae, brick warehouses whose concrete vaulting kept grain dry. A weekly ration—originally grain, later baked loaves—reached 320 000 adult citizens. Bread on the table translated into social peace and a voter base loyal to emperors able to keep the wheat ships sailing.

Law: From the Twelve Tables to the Corpus Juris

The Twelve Tables of 451 BC wrote down procedure for wills, debts, and homicide so plebeians could see the rules once monopolised by patrician priests. Over time jurists like Gaius sketched universal concepts—good faith in contracts, strict liability for dangerous animals—that transcended local superstition. Governors received edicts summarising permissible taxes, court fees, and appeal paths. A merchant from Massilia could sue a partner in Antioch under familiar forms. Even emperors bowed to procedure: Hadrian returned property to a widow after jurists proved a confiscation order misapplied precedent. Justinian later sorted centuries of opinions into the Digest, creating a code that would guide Byzantine, Islamic, and eventually Napoleonic legislation. Uniform law lowered transaction costs across three continents, knitting markets together as securely as mortar binds stone.

Citizenship as Grand Strategy

Rome’s genius lay in its willingness to share status. After the Social War, Italian allies gained full rights; their grandsons seated themselves in the Senate. Claudius admitted Gauls to the purple‑striped benches, arguing that ancestors of contemporary Romans had once been Etruscan newcomers. By 212 AD Caracalla’s Constitutio Antoniniana made every free provincial a citizen. The edict expanded the inheritance tax base but also broadcast a message: the empire belonged to all who paid its levies and kept its peace, regardless of tongue or birthplace. That promise undercut rival identities and gave former subjects a stake in defending imperial order.

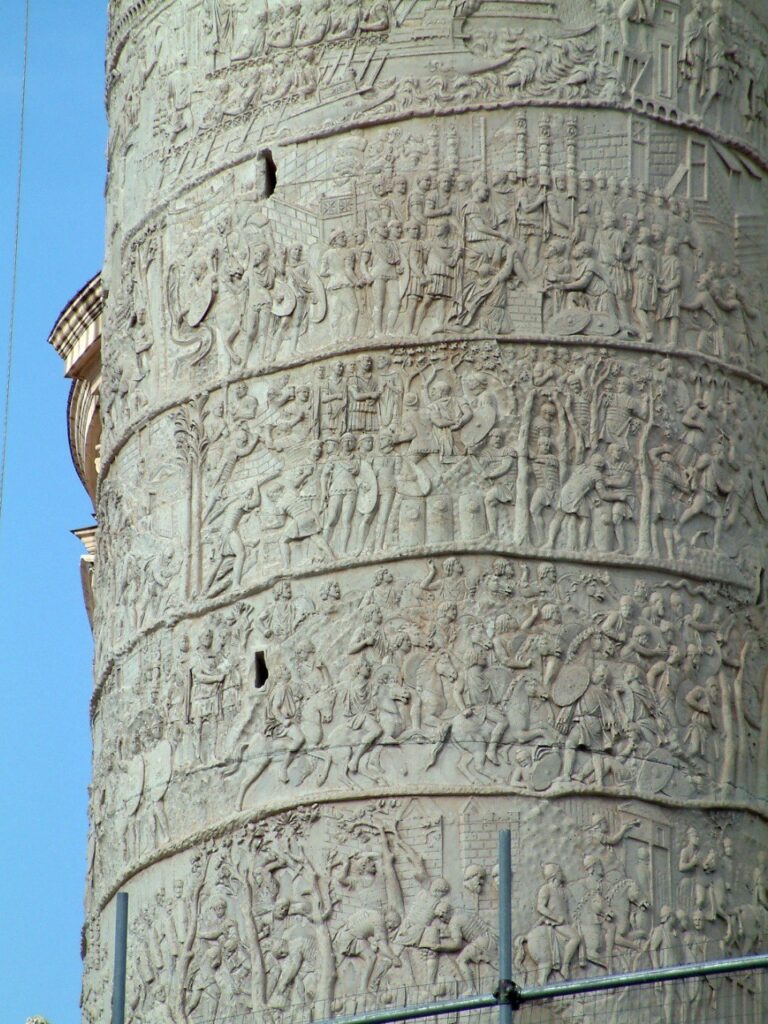

Cities in Imperial Image

Colonies acted as radiators of Roman habit. Timgad, founded by Trajan in 100 AD, followed a textbook grid of right‑angled streets converging on a central forum, basilica, and Capitolium. Theatre seating echoed the political hierarchy—broad marble steps for decurions, narrow wooden benches for freedmen—teaching newcomers how rank mapped onto space. Aqueducts poured through arched gateways bearing the imperial eagle, while bath complexes hosted business deals with more efficiency than any boardroom. Archaeologists have mapped nearly forty amphitheatres outside Italy, proof that civic spectacle traveled with engineers and masons who carried architectural blueprints rolled beside their survey poles.

Frontiers: Walls, Diplomacy, and Depth

Rome seldom relied on a single line of stone. Along the Rhine and Danube, a forward belt of forts screened patrol zones patrolled by auxiliary cohorts recruited locally. Behind them lay towns whose markets sold wine, pottery, and salted fish to soldiers paid in imperial coin. A third belt consisted of client kingdoms subsidised to absorb the first wave of invasion. Hadrian’s Wall in Britain marked one variation: an 118‑kilometre curtain punctuated by milecastles and gatehouses that taxed traders even as it impeded raiders. Subsidies to northern tribes bought further breathing space. This layered defense minimised the need for massive garrisons, freeing legions for offensive thrusts when opportunity beckoned.

Economic Integration and the Denarius

Monetary uniformity matched the legal and logistical web. The silver denarius introduced in 211 BC weighed 4.5 grams, stamped first with Roma’s helmeted head, later with portraits of emperors. Merchants in Lusitania trusted the coin’s weight and purity as much as bankers in Antioch did, enabling long‑distance contracts without barter risk. Periodic debasements—most notoriously under Nero and again during the third‑century crisis—triggered price spikes, yet each reform that restored silver content also restored confidence. Diocletian fixed tax liabilities in kind, reducing exposure to currency swings, while Constantine’s gold solidus stabilised imperial finances for centuries. Hard money kept building projects funded and legion payrolls punctual, reinforcing the perception that Rome was synonymous with order.

Cultural Flexibility

Rome absorbed gods as readily as provinces. Syrian merchants brought Mithras; Egyptian priests carried statues of Isis; Greek settlers re‑interpreted Jupiter through the lens of Zeus. Rather than eradicate foreign cults, emperors folded them into a mosaic of public religion, demanding loyalty to the imperial genius more than theological uniformity. Latin spread as the bureaucratic language of law and command, yet Greek retained prestige in medicine, philosophy, and commerce. Bilingual inscriptions in Lepcis Magna list imperial edicts first in Latin, then in neo‑Punic or Greek, ensuring comprehension without coercion. This multilingual pragmatism fostered loyalty where forced homogeneity might have bred revolt.

Government by Adaptation

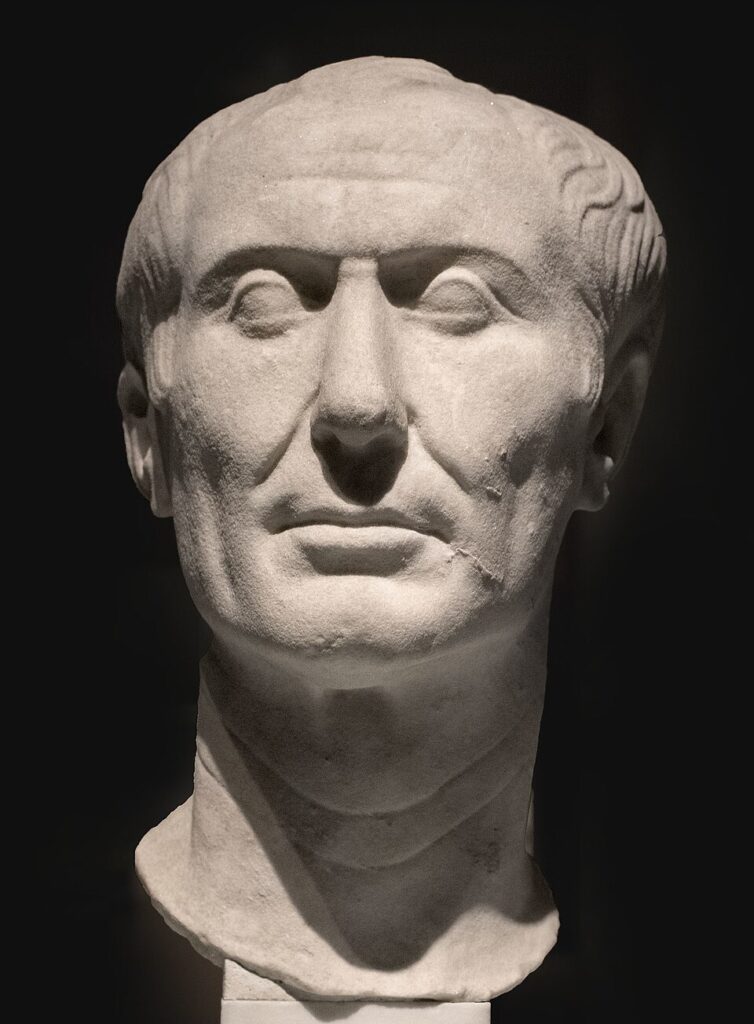

The Republic proved unable to police an empire, prompting Augustus to fuse autocracy with republican ritual. Later emperors tweaked the blueprint rather than scrap it. Hadrian abandoned expansion in favor of consolidation, ordering the first empire‑wide census since Augustus. Septimius Severus raised legion pay and allowed soldiers to marry, stabilising garrisons blighted by desertion. Diocletian’s tetrarchy split command among four co‑emperors, making civil war less tempting by dividing spoils. Constantine legalised Christianity, aligning imperial authority with a rapidly growing moral network that crossed ethnic lines. Each pivot kept the old skeleton—law, roads, legions—while shedding political skin that no longer fit.

Crisis and Renewal

Pandemics, mutinies, and economic shocks hit hard in the third century. The Antonine plague may have halved some provincial populations; coinage debasement drove inflation to dizzying heights; breakaway states emerged in Gaul and Palmyra. Yet Aurelian marched 8 000 kilometres in five years, restoring the map and erecting the massive Aurelian Walls around Rome. Diocletian followed with tax reforms pegged to land surveys and head counts. Constantine’s founding of Constantinople exploited eastern wealth when the western Mediterranean faltered. Each recovery bought the system another century of life, showing that restoration, not mere resilience, lay at the heart of Roman strategy.

The Eastern Thread

When Odovacer removed the last Western emperor in 476 AD, provincial governors in Antioch and Alexandria continued to date edicts by the reigning emperor in Constantinople. Justinian’s reconquest of Italy and North Africa in the sixth century briefly restored the old boundaries, while his legal commission edited the Corpus Juris that still underpins civil law from Québec to São Paulo. Byzantine coinage carried the Latin word CONOB (“Constantinopolitan standard gold”) until the eleventh century. The eastern half finally fell to the Ottomans in 1453, nearly 1 700 years after the first bricks of the Servian Wall were laid. Few polities can match such continuous institutional memory.

Legacy Beyond Borders

Modern highways shadow Roman roadbeds; European civil codes echo Latin maxims; American senators convene under a title borrowed from a plebeian assembly. Concrete that resists salt water carries container ships through global harbours—a recipe first perfected by Roman engineers lining docks at Caesarea Maritima. The empire’s genius lay not in any single innovation but in the synergy of many: citizenship policies that co‑opted talent, infrastructure that shortened distances, and law that bound strangers into predictable relationships. These components formed a self‑reinforcing loop that endured a millennium and still threads through daily life across continents.