Tyr and Ares stand at opposite ends of the ancient imagination about war. Both are called war gods, yet the similarities end quickly. In Norse myth, Tyr is the trusted hand of law and honour, the one who makes and keeps oaths, even at great cost. In Greek myth, Ares is the raw storm of battle — fearless, loud, and often unwelcome in polite company. The contrast says as much about the cultures that shaped them as it does about the gods themselves.

By setting them side by side, you see how two warrior ideals can take entirely different forms. Tyr’s courage is quiet, bound to duty and self-sacrifice. Ares’ power is noisy, tied to bloodlust and the thrill of combat. Both are formidable. Both inspire. But the reputations they hold in their own pantheons could hardly be more different.

Who Tyr is in Norse myth

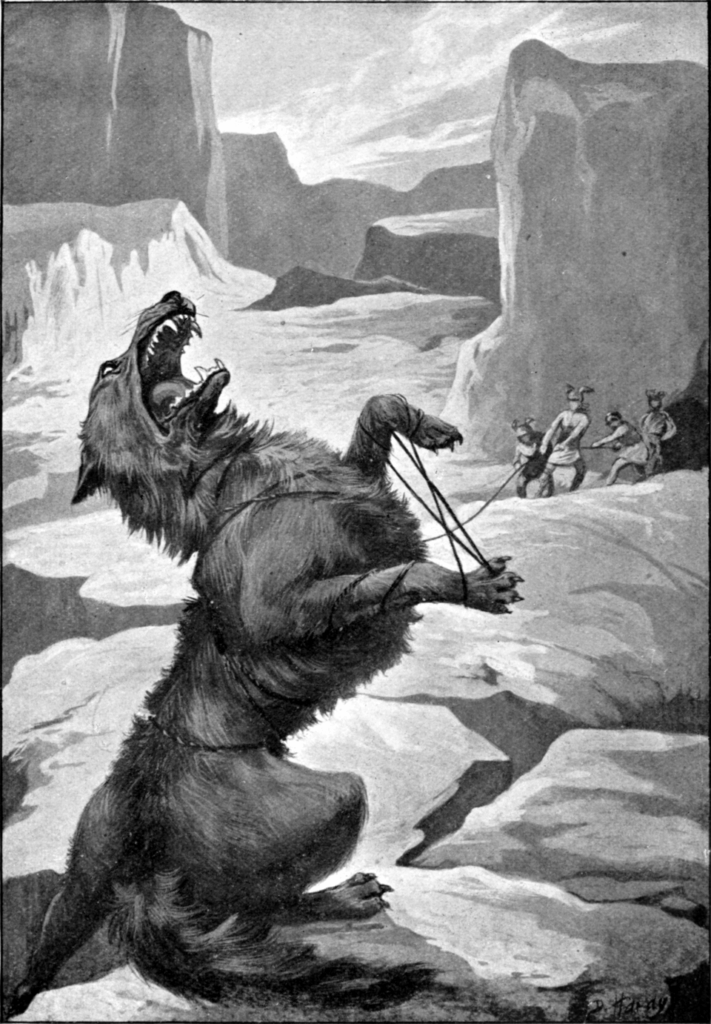

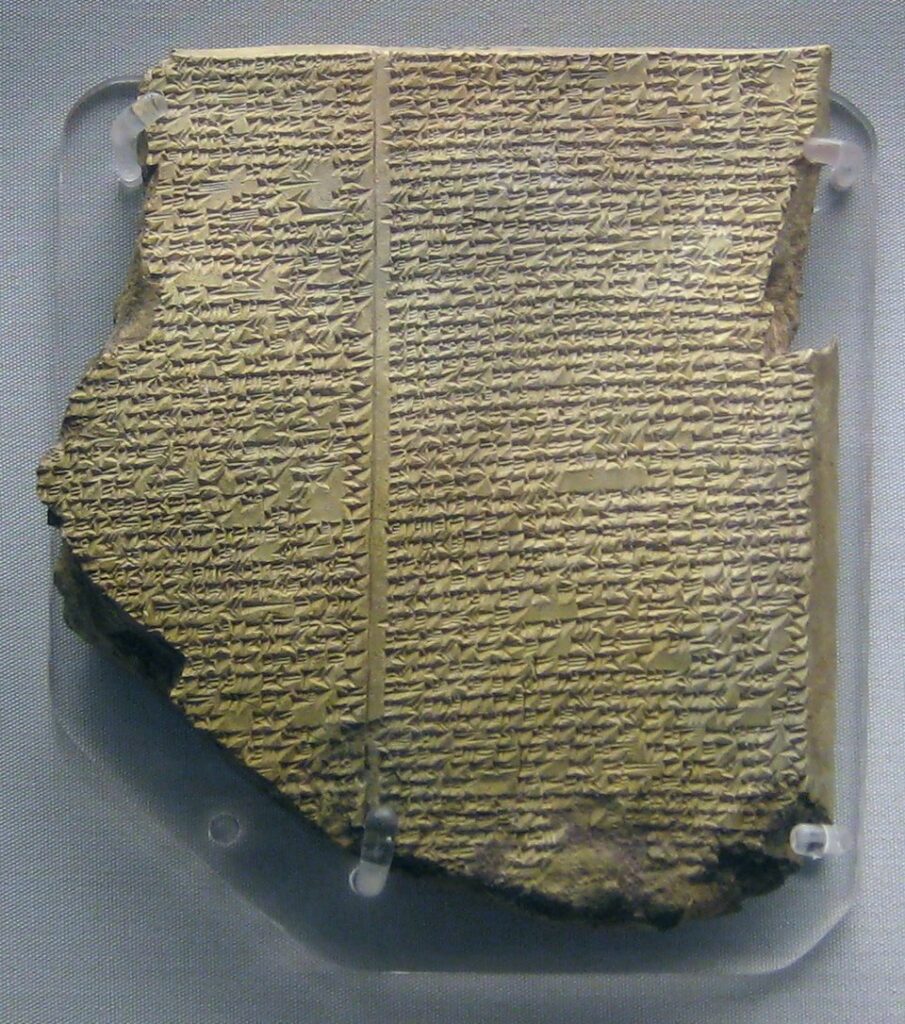

Tyr’s name survives in Tuesday — Týr’s day — a reminder of his status in the old Germanic pantheon. In the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda, his defining act is the binding of the monstrous wolf Fenrir. The gods raise Fenrir among them but fear his strength. They try to bind him with chains, all of which he breaks. Finally, they commission a magical fetter, Gleipnir, woven from impossible things. Fenrir grows suspicious and demands a pledge of good faith: one god must place a hand in his mouth while the binding is tested.

Tyr volunteers. When Fenrir finds he cannot break Gleipnir, he bites off Tyr’s hand. The loss marks Tyr forever, not as a victim but as the god who kept his word even when the cost was personal ruin. In battle, this sense of oaths and rightful war defines him. He is not the loudest or most violent among the Æsir, but he is the one they trust to stand in the breach when honour is on the line.

Ares in Greek myth

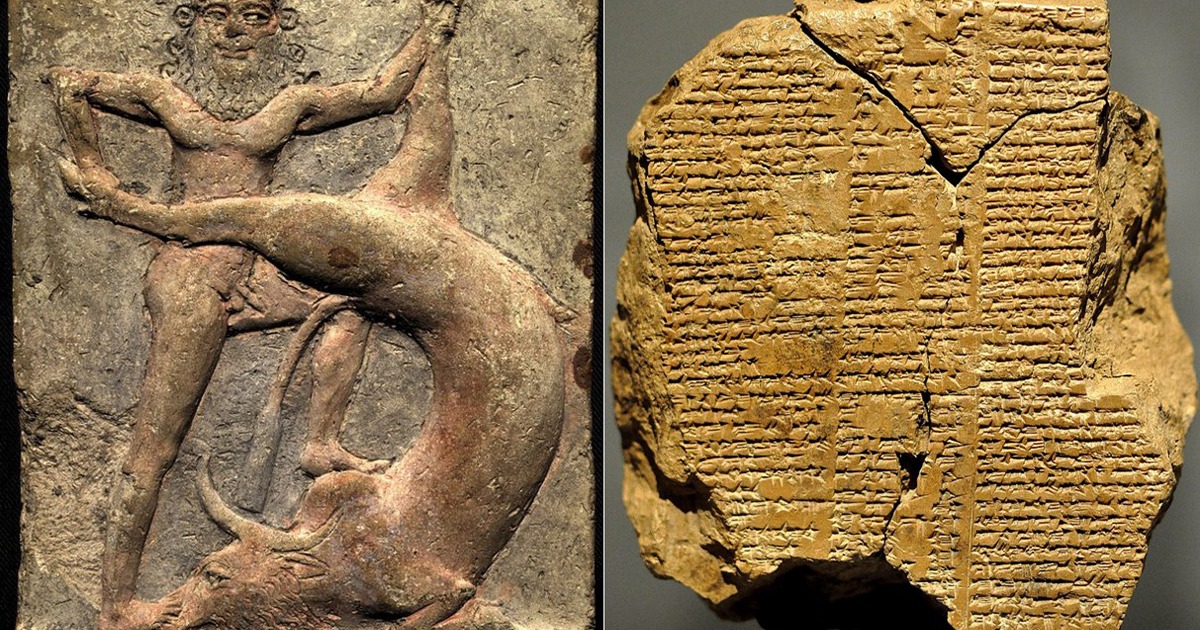

Where Tyr commands respect, Ares inspires mixed feelings. The Greeks honoured him as a god of war but rarely celebrated him in peacetime. In Homer’s Iliad, he takes the field with eagerness, yet even other gods complain about his recklessness. Zeus calls him “most hateful” among the Olympians for his constant delight in strife. Ares represents the chaos and bloodshed of battle, the side of war that leaves cities smouldering and families broken.

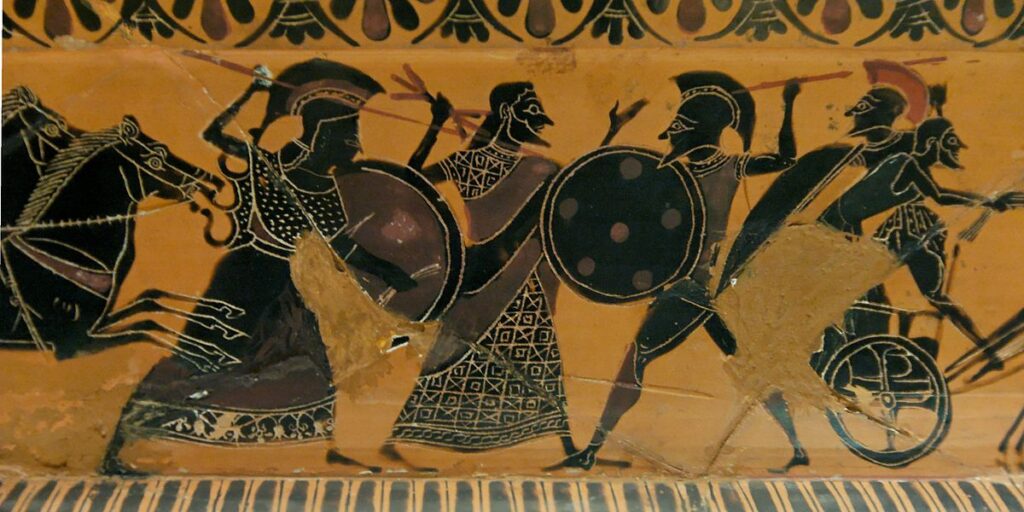

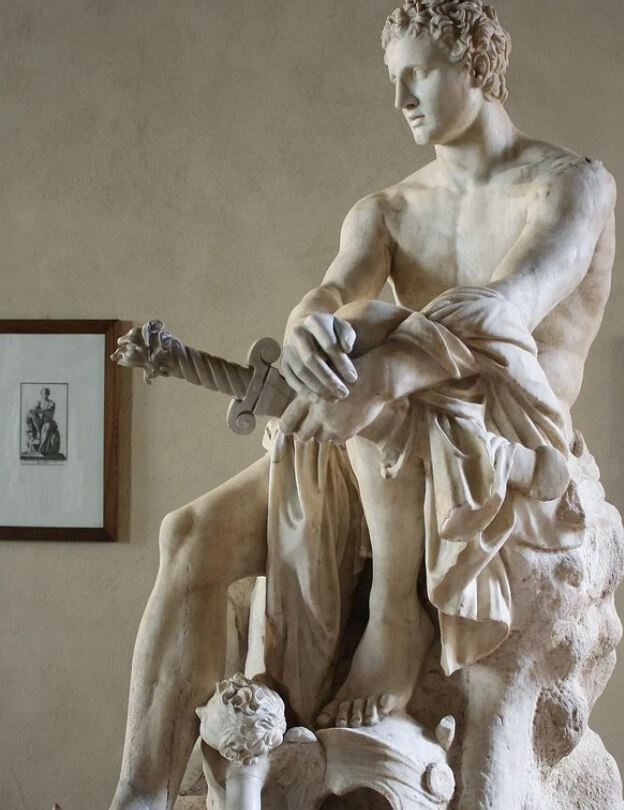

Yet his power is real. He charges into conflicts without hesitation, often accompanied by his children — Phobos (Fear) and Deimos (Terror) — who ride ahead to unnerve foes. In Greek art, he is the well-armed warrior, helmeted and ready, sometimes shown with his lover Aphrodite. The myths do not hide his defeats; Athena, goddess of strategic war, bests him more than once. The lesson is clear: raw force has limits, and without discipline, it can be turned aside.

Different cultures, different war

The reputations of Tyr and Ares grow from the values of the societies that worshipped them. Norse myth developed in a world of shifting alliances, where oaths and honour could mean survival. A god who safeguarded contracts and punished oath-breakers would be central. Greek myth took shape in city-states often in rivalry, where war was frequent and could be both a source of glory and a destructive curse. Ares embodies the dangers of unrestrained violence, a warning alongside his role as a patron.

In practical terms, Tyr is invoked before legal assemblies as well as in battle. He is tied to the thing, the gathering where disputes are settled. Ares, by contrast, presides over the field of battle itself — his sacred site in Athens, the Areopagus (“Hill of Ares”), later became the city’s court for homicide trials, but even that role kept his link to blood and vengeance.

Symbols and worship

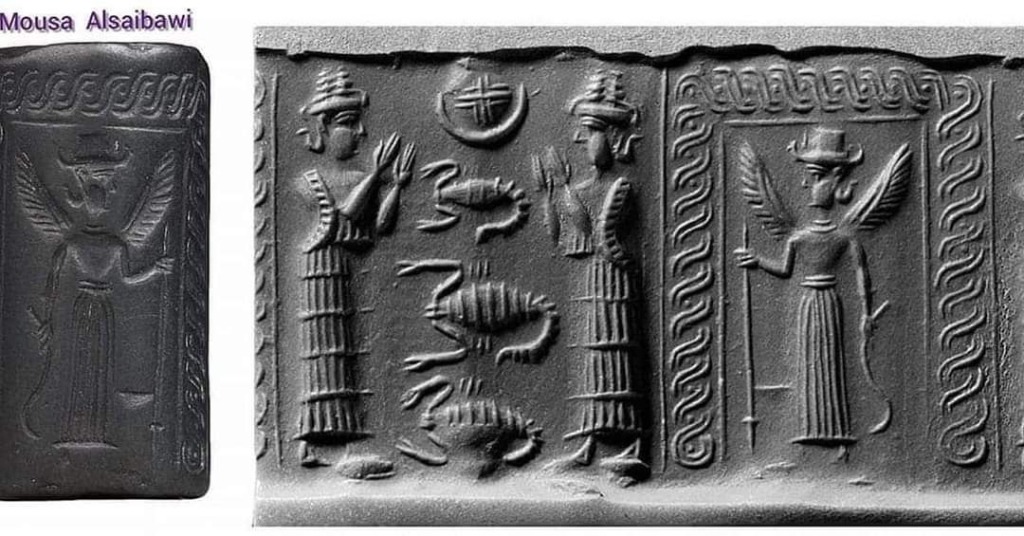

Tyr’s symbols include the spear and the scales of justice. He is sometimes shown with only one hand, a visual shorthand for his sacrifice. There are fewer surviving images of Tyr than of Thor or Odin, but runic inscriptions bear his name, and his role is felt in the legal oaths sworn in his name. In the wider Germanic world, he may have been even more prominent in earlier centuries, possibly once the chief sky god before Odin rose in importance.

Ares’ symbols are easier to trace: the spear, helmet, shield, and sometimes a chariot drawn by four fire-breathing horses. Temples to Ares were rarer than to other Olympians, but he received offerings from warriors before campaigns. In Sparta, where military life was central, he was more honoured than in other Greek cities. His presence on armour and shields acted as a talisman, calling for courage in the clash.

War as honour vs war as chaos

Tyr’s mythology frames war as something that can be just or necessary, but always bound by rules. His most famous act is not about killing an enemy but about keeping faith with one — even a dangerous one — to maintain order. In a society where betrayal could shatter alliances, this image mattered.

Ares’ myths lean into the heat of battle: sudden charges, blood on the ground, the scream of warriors. He is the surge of adrenaline, the loss of restraint, the momentum that can turn a fight. That energy can win a day, but it can also destroy more than it saves. Greek storytellers made this point by showing him wounded, humiliated, and even chained by giants — power checked by those who can outthink him.

Encounters with other gods

Tyr does not dominate Norse myths in the way Odin or Thor do, but his presence is steady. He fights beside the Æsir against the giants, joins councils, and in the end, is fated to face the monstrous hound Garmr at Ragnarök. They kill each other, an ending that matches his life: sacrifice in the line of duty.

Ares interacts with many Olympians, but his relationship with Athena defines his arc. In Homer, she wounds him and drives him from the battlefield. The contrast is sharp: she plans, he charges. The tension between them is less about personal dislike and more about their roles — strategy versus impulse, order versus passion.

Lessons they embody

From Tyr, the lesson is that strength is hollow without integrity. War, in his world, is a last resort to defend the law, uphold an oath, or protect the community. The glory comes in doing the hard thing for the greater good, even when it costs dearly.

From Ares, the lesson is double-edged. Courage and fury can carry a warrior far, but without restraint, they can ruin the very cause they fight for. Ares’ defeats are as instructive as his victories, showing the need for balance between force and foresight.

Why the comparison matters now

Comparing Tyr and Ares opens a window into two philosophies of conflict. The Norse tradition values the binding word; the Greek tradition recognises the danger of unbound force. Together, they sketch a spectrum that still matters in thinking about power, leadership, and the ethics of war. In modern terms, Tyr is the disciplined commander who follows the rules of engagement; Ares is the shock troop leader whose ferocity can win or waste a battle.

Enduring images

Neither god vanished with the decline of their worship. Tyr lives on in language and in revived Norse-inspired practices. Ares walks through art and literature, sometimes merged with Mars, his Roman counterpart, who was more disciplined and civic-minded. They surface in novels, games, and even political commentary, their traits mapped onto modern figures.

The persistence of their images speaks to the universality of their archetypes: the honour-bound warrior and the untamed fighter. Both are necessary in different moments. Both can be dangerous if misplaced. That tension keeps their stories alive and relevant, long after the last formal sacrifices were offered in their names.

A closing thought

Set Tyr and Ares on the same field, and the outcome is hard to call. Tyr’s strategy and trustworthiness might outlast Ares’ fury, but in the first clash, Ares’ sheer force could overwhelm. The more interesting point is not who would win, but how each would fight — and why. In that difference lies a whole world of cultural values, ancient yet recognisable, still shaping the way we think about war and those who wage it.