The Dogon of Mali live along a dramatic sandstone wall that runs for more than a hundred kilometres across the Sahel. Villages cling to ledges, granaries rise on stilts, and mask dancers turn courtyards into theatres of dust and song. For many readers, though, the first thing they hear about the Dogon is not the cliff or the masks. It is a claim about a star. The story says the Dogon knew that Sirius, the brightest point in the night, has an invisible companion and that the pair move around one another in a long, orderly cycle. That sounds impossible for a society without telescopes. It also makes for headlines. What happens when we slow down, read the sources, and listen to Dogon voices today.

Two paths run through this subject. One follows cosmology and ritual in a West African community that has held on to distinct practices for centuries. The other follows an argument in twentieth-century anthropology about field methods, interpretation, and how outsiders handle knowledge. Walk them together and the “Sirius mystery” turns from a simple puzzle into a fuller story about how ideas travel and change.

The land and the people

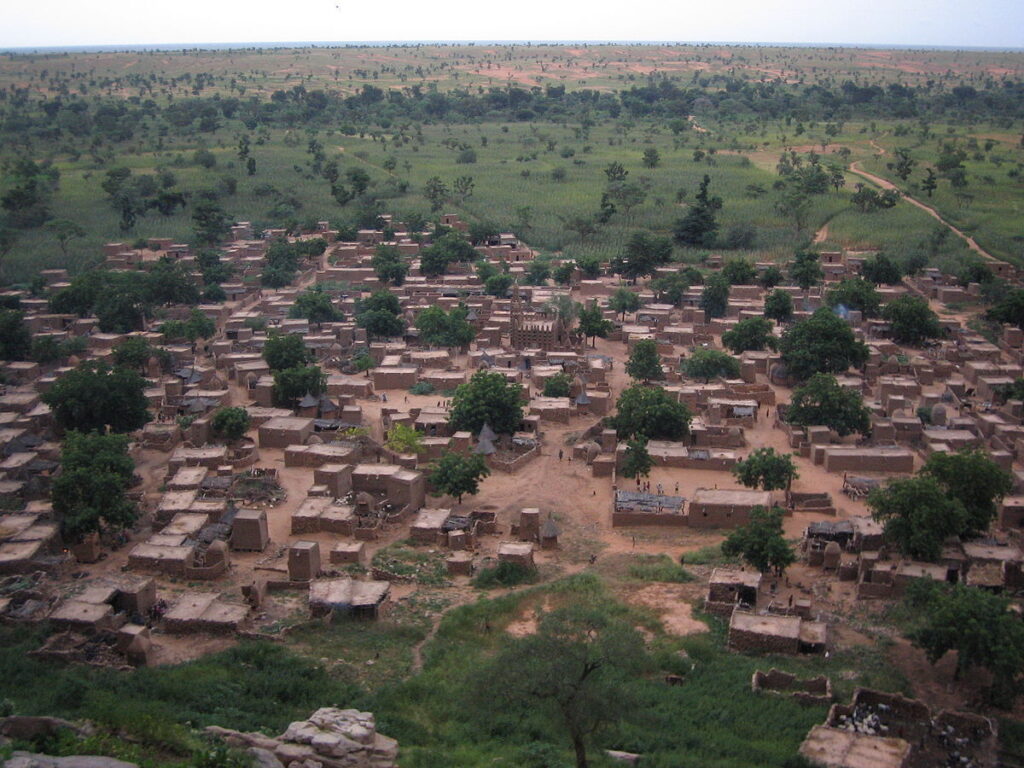

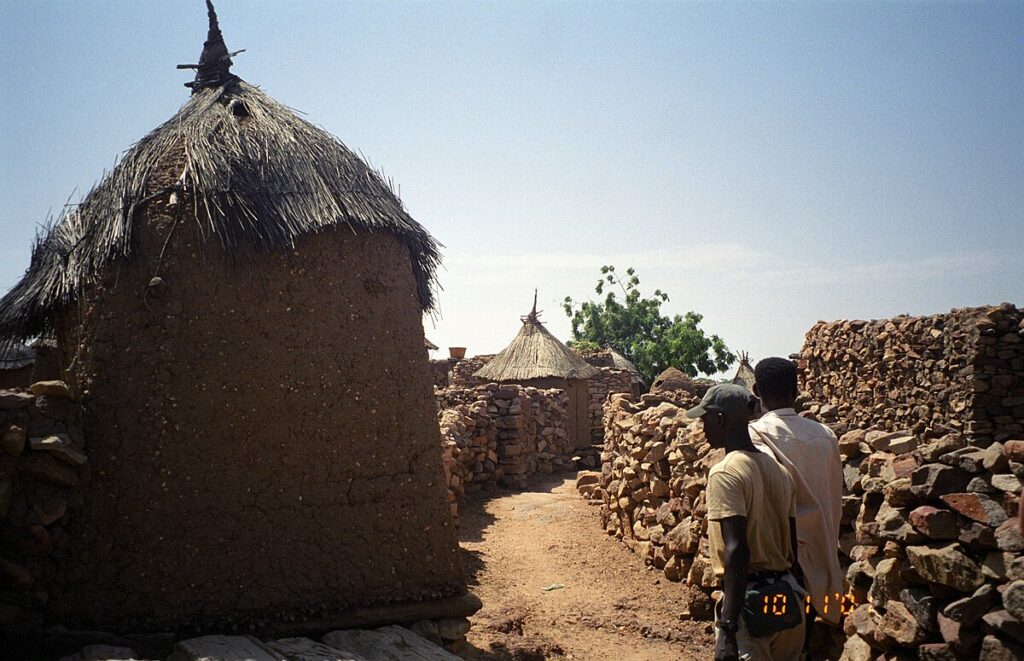

The Bandiagara escarpment sets the stage. It is a long cliff with shelves, caves, and high plateaux. It shelters villages from wind and gives easy watch over the plains below. Earlier peoples, the Tellem and the Toloy, left traces high in the rock. The Dogon moved into the area centuries ago and shaped a cultural landscape of houses, shrines, toguna meeting halls, and storage towers for millet. UNESCO lists the escarpment for its combined geological, archaeological, and living heritage, noting the continuity of ritual, architecture, and craft across the region. The site’s scale and depth make it one of West Africa’s most striking cultural terrains. :contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}

Daily life here carries strong rhythms. Farming follows the rains. Masks appear at funerals and large cyclical rites. Family compounds grow around courtyards. Granaries, male and female, store grain and personal goods, and their forms declare status and care. Houses and shrines use local earth, wood, and fibre, so the villages feel rooted in the cliff from which they rise. This setting frames the cosmology. Stars, seasons, and ancestors all belong to a single fabric of practice.

What the “Sirius mystery” claims

The popular version runs like this. The Dogon hold a complex cosmology that includes Sirius A, the bright star in Canis Major, and a hidden companion, sometimes called po tolo. According to the claim, po tolo is small, heavy, and moves in a long orbit, which modern astronomy describes for Sirius B, a white dwarf. The story links this to a grand festival, the Sigui, said to recur on a cycle connected to Sirius. Some writers add further details, or suggest a second unseen body, and a few leap to fantastical conclusions about extraterrestrial visitors. Those leaps often sell books, yet they do not help us understand Dogon thought on its own terms.

To unpack the claim, we need to ask where it came from, how it was recorded, and what later work found. That means meeting a handful of anthropologists and the debates their work sparked.

Where the idea comes from

French ethnographers Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen spent many seasons with Dogon communities in the mid-twentieth century. They published major studies of masks and ritual and, in 1950, a short paper titled “Un système soudanais de Sirius.” That piece set out a cosmological scheme in which Sirius and associated terms played roles in Dogon thought. Later publications elaborated this material, presenting an intricate chain of symbols, star names, and cycles. These texts shaped how outsiders talked about Dogon astronomy for decades.

In time, the work met scrutiny. Some astronomers and sceptics questioned whether the details were recorded accurately, or whether observers brought their own expectations to interviews. Others pointed to the risk of contamination. News about Sirius B had been public in Europe for years, and educated West Africans moved through trading towns and missions where such talk travelled. The question was not whether the Dogon looked at the sky, which they obviously did, but whether the specific claims about an invisible companion and its orbit truly belonged to Dogon tradition before outside contact.

What later fieldwork reported

In 1991, Walter E. A. van Beek published a long restudy that compared his years of fieldwork with the earlier French accounts. He found no general Dogon knowledge of the Sirius scheme as presented by Griaule and Dieterlen. Informants did not link the Sigui festival to an astronomical period for Sirius, and terms like po tolo appeared with other meanings, including a seed used as a symbol of smallness and density. The paper argued that the earlier system likely resulted from a unique field situation, particular informants, and strong guiding questions. The debate is sharp, but it remains the key reference for anyone writing about the Dogon and Sirius today.

Van Beek returned to the topic years later, reflecting on method and memory in Dogon studies. He described how prestige, translation, and the dynamics of a long research relationship can shape what ends up on the page. The result is a cautionary tale. Beautiful systems can emerge when an eager scholar meets a willing expert, yet community-wide knowledge may look different. For readers, this means treating the “mystery” as an argument about sources rather than a proof of secret science.

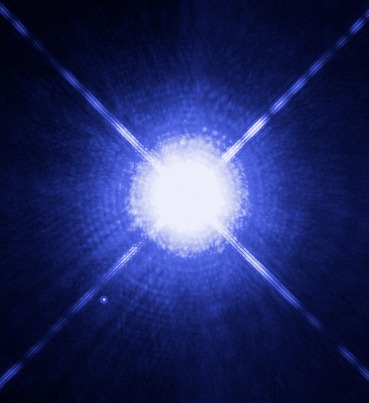

What astronomy actually says about Sirius

Sirius A is bright enough to fix its place in navigation and myth across continents. Sirius B is a white dwarf. The pair move around a common centre roughly every fifty years. Modern images, including those from the Hubble Space Telescope, show the faint companion near the glare of the main star. That is a difficult observation without instruments, so popular accounts often jump from “hard to see” to “impossible,” which is not quite the same thing as “unknown.” People can hear about things they cannot observe. Traders, teachers, and radio carried such talk across West Africa in the twentieth century.

None of this denies that the Dogon pay attention to the sky. It simply draws a line between a community’s sky-lore and a very specific scientific picture that belongs to modern astronomy. The two can meet. They can also pass by. Careful writing shows where each kind of knowledge stands.

The Sigui festival and the problem of cycles

The Sigui is a vast ritual cycle with processions, masked dances, and renewal of social roles. Outsiders often compress it to a single number, then map that number onto an orbital period. Real life is messier. Communities adjust timing to social and historical needs, and the festival can run over several years. Linking it cleanly to a precise astronomical clock looks neat on paper. It does not match the full range of practice reported on the ground. This is exactly where long fieldwork helps. It records variation and keeps us from forcing ritual life into tidy graphs.

Dogon cosmology on its own terms

Dogon thought is rich without any appeal to impossible knowledge. Myths remember a first world that fractured, a creative word that shaped matter, and the difficult task of keeping order. Ancestors and masks fold those themes into daily life. Crafts carry meaning. Carved doors and posts tell stories in short, repeating signs. Divination tracks the pale fox, whose prints mark chance and choice. In this frame, stars matter as part of a whole. They join winds, animals, and seeds in a network of correspondences that tie the cliff to the sky.

Consider the granary. Its round plan and thatched cap have clear functions, yet people also read it as a model of the world. Seed inside suggests potential. The door carries signs that speak of protection, fertility, and time. A cosmology that uses grain and sky together is not naïve. It is practical poetry, built from things at hand.

How myths travel and shift

Knowledge is social. Traders, soldiers, teachers, and tourists pass through the Dogon country. Mission schools once taught European astronomy. Radios carried news in French and Bambara. A striking idea can land in a village and find a welcome place within an existing myth. Over time, borrowed details settle into local terms. The result is not fraud. It is culture at work. This is how myths everywhere grow and bend, whether in Rome, Benin, or Bamako.

That is why scholars care about dates and contexts. A detail recorded in 1931 carries different weight from one taped in 1970. A statement from a single expert differs from one confirmed across several elders from different villages. These distinctions feel fussy to casual readers, but they protect against turning a conversation into a creed.

Reading popular books with care

The “Sirius mystery” jumped from scholarly journals to mainstream shelves in the 1970s. Popularizers joined the dots in dramatic ways, sometimes bringing in extraterrestrials or ancient visitors. Reviews at the time noted how much of this rested on the early ethnographies and how little cross-checking had been done. For students, these episodes are useful. They show how fast a neat diagram can outrun the footnotes. The lesson is simple. Read the field reports. Then read the rest with curiosity and caution.

The landscape that holds the story

It helps to step back and look again at the cliff. Villages and shrines draw a line between rock and plain. Paths thread along the base. Granaries, male and female, punctuate the skyline. UNESCO’s listing remarks on the interplay of architecture, ritual, and landform, which is exactly what a visitor feels. In recent years, conflict in Mali has strained local life and damaged heritage. International projects have worked with communities to stabilise buildings and safeguard ceremonial objects. Cultural survival needs both peace and patient repair.

When people discuss the Dogon, they often jump straight to the star. The place itself deserves the first look. A cosmology grows in a setting, and the Bandiagara landscape explains much about Dogon priorities. Grain must be safe from mice and rain. Paths must manage steep ground. Meeting halls must shade speech. In that daily work, myth breathes.

What we can say clearly

First, the Dogon have a deep, layered cosmology that runs through craft, ritual, and story. Second, the most dramatic claims about secret knowledge of Sirius come from a specific strand of mid-century ethnography and do not appear widely in later field reports. Third, modern astronomy confirms that Sirius has a white dwarf companion with a long orbit, and modern images make it visible near the glare of the bright star. Fourth, it is sensible to keep the categories straight. Sky-lore and science meet at points, but they answer to different rules of evidence.

These points leave space for wonder without short-cuts. They also leave room for Dogon knowledge to stand as Dogon knowledge, not as proof of an exotic theory. Respect shows in details, and in patience with sources.

Why the story endures

It endures because it is tidy, dramatic, and flattering to readers who want mystery in every corner. It also endures because the Dogon are genuinely compelling. Their masks, architecture, and rites have power. A star gives outsiders an easy way in. Our job is to make sure the path leads to the people and their place, not just to a talking point.

Besides, the real questions are interesting enough. How do communities anchor memory over centuries. How do rites absorb change and still feel old. How do crafts teach children what a myth means. These questions connect the Dogon to everyone else. The answers are written in wood, fibre, millet, and song.

Seeing and reading the Dogon well

Good visits begin with local guides and time. A morning at the base of the cliff teaches more than a week of headlines. Granaries tell their own stories. Masks come alive when you hear the rattle and feel the ground jump. A quiet hour in a toguna explains how shade and short roofs keep tempers cool. Photographs are welcome in some places and not in others, and permission is key. Even from afar, open collections and museum catalogues offer strong images and careful notes that help readers see the difference between temper and fact.

Once you have that foundation, the sky talk becomes easier to place. Sirius is a bright point with a well-understood companion. The Dogon see the same sky the rest of us do. Their cosmology makes different use of it, binding star and seed into a single fabric. That is not a failure of science. It is the mark of a culture that knows how to think across domains.

Putting the “mystery” back in context

Strip away the hype and you have a useful case study in how research works. One team records a complex system. Another team returns and finds a different picture. The community itself changes as decades pass. Global media lift a few lines and make them carry more weight than they can bear. Readers step in at different points and pick the version that suits their taste. The antidote is straightforward. Compare field reports. Note dates. Weigh methods. Keep the landscape and the people in the frame.

When you do, the Dogon look even more impressive. The question is no longer, “How did they know a white dwarf orbits Sirius.” It becomes, “How did they hold a living ritual system together across hard seasons and hard years.” That is a real achievement, and it belongs to them.

Granaries, stars, and the scale of meaning

One last image helps. Imagine a farmer unlocking a granary at dawn. The roof keeps out rain and heat. The walls keep out mice. Inside lies the next month’s food and seed for the next season. For the Dogon, that small tower also holds meanings that reach beyond the village. A seed can stand for beginnings. A door carving can fix a promise. A pattern can remember a story. Stars enter that field of signs and lend it a wider horizon. The meeting of the intimate and the immense is not strange here. It is the way the world holds together.

A measured ending

Call it a mystery if you like, but do not stop at the slogan. The Dogon give us a chance to see how people build meaning from land, craft, and sky. They remind us that stories travel and that careful listening matters. They also invite us to enjoy a night under the Sahel stars with good company, where the bright point of Sirius rises over the cliff and the village settles into quiet. The sky is old. The questions are too. The answers are richer when we let the people who live with them speak first.