Before pamphlets, radio, or television, the Neo-Assyrian kings learned to work on the mind. They turned fear into an instrument. They staged scenes of victory in palace halls. They put captives on display. They wrote annals that made enemies feel small before a single spear was raised. The result was a style of rule that pushed beyond swords and chariots. It was theatre, message discipline, and calculated cruelty. If you want an early blueprint for psychological warfare, you find it in the stone walls of Nineveh, Nimrud, and Khorsabad.

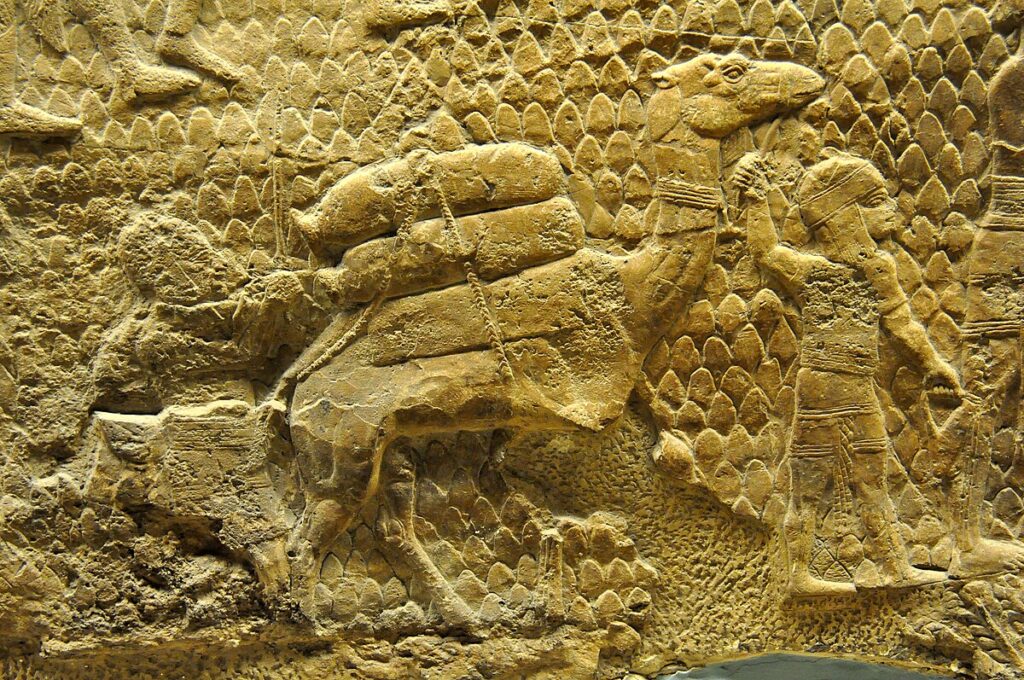

Assyrian armies did not simply win. They made sure everyone knew they had won, how they had won, and what would happen to the next city that hesitated. Reliefs show siege ramps creeping up walls, defenders tumbling, then processions of deportees. Inscriptions boast of kings “treading down like locusts,” shutting rulers “like a bird in a cage,” and hanging the skins of rebels on gates. The point was not subtle. Yield and live. Resist and learn why resistance was a bad idea.

Empire built on memory

Fear fades quickly if you cannot bottle it. Assyrian palaces solved that problem. Long galleries carried carved narratives of conquest so that visiting envoys, governors, and petitioners walked through a lesson in power. Each slab repeated the same message in different clothes: this is what happens when you cross us. The halls worked like permanent press briefings. Courtiers absorbed details. Messengers carried them outward. Local rulers saw their own future in the figures of other defeated kings.

The carvings are precise. Engineers raise earthen ramps while archers and slingers cover them. Battering rams press shields against walls. On the edges, officers count spoils, take hostages, and catalog tribute. After the fight, lines of families trudge away under guard, hands lifted in supplication, ox-carts loaded with goods. A few scenes record the ugly end of captured leaders. None of this is accidental. It is choreography for the mind.

Words as weapons

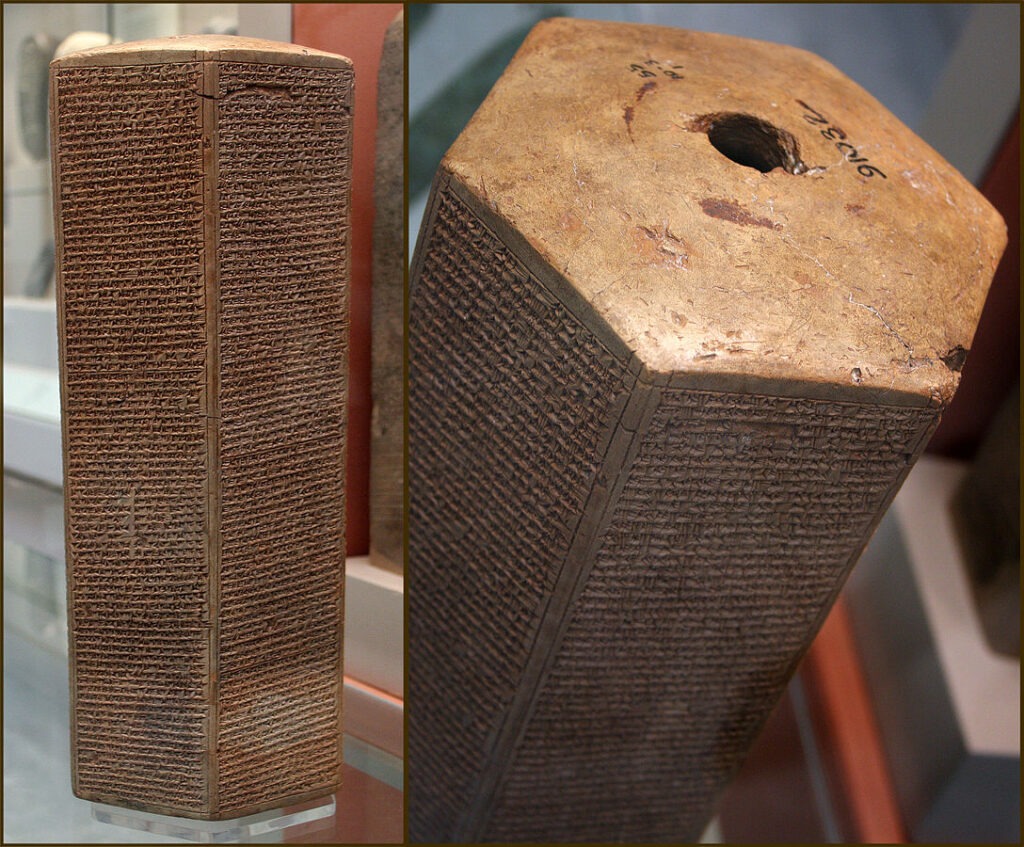

Stone spoke; clay spoke louder. Royal annals, etched in tidy wedges on hexagonal prisms and clay cylinders, travelled as copies to temples and provincial centres. They announce campaigns, list cities flattened, and dwell on punishments for rebels. One record famously claims to have shut Hezekiah of Judah “like a bird in a cage.” The phrase is not just brag. It is a hook designed to lodge in a ruler’s thoughts when the next Assyrian envoy appears. If a king in Jerusalem felt caged, what hope did a smaller city have?

These texts also display a careful balance of terror and order. The king punishes the stubborn, but he reinstates the compliant and returns fields to those who bow. There is always a door back to safety—if you accept terms. Mercy appears, but only on the empire’s terms. That contrast does its own work: fear motivates; the promise of stability closes the deal.

A case study carved in gypsum: Lachish, 701 BCE

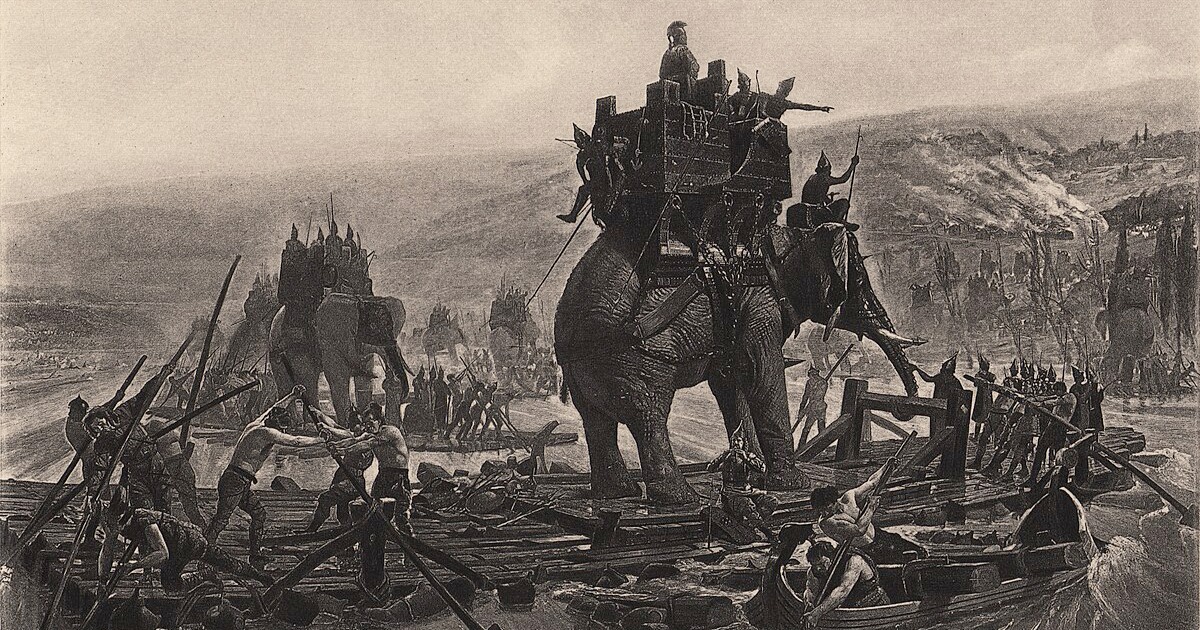

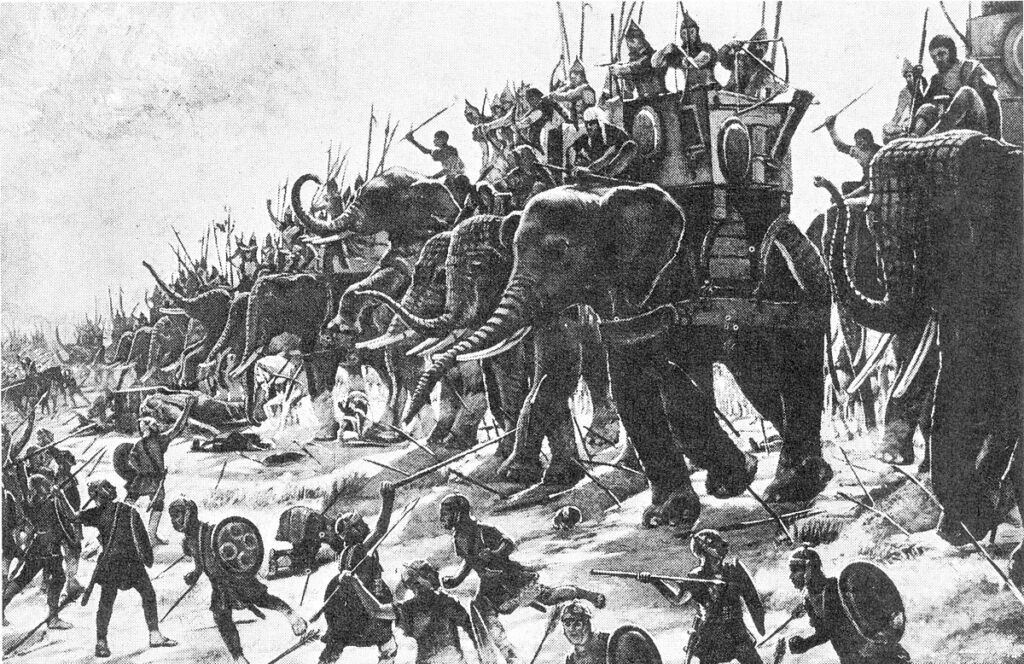

Walk the Lachish reliefs and you watch psychological warfare step by step. First comes the approach: troops in ranks, wicker shields interlocked, rams inching forward, engineers piling the ramp. Siege is a performance. The defenders are meant to see each stage arrive, and to feel their options narrow.

Then the breach: archers lay down fire; the rams bite the wall; soldiers climb ladders. Assyrian artists make sure we read the confidence on the attackers’ side—orderly rows, disciplined posture. On the other side, chaos. Figures fall from towers. Torches tumble.

Finally, the lesson: prisoners file past the king on his throne; scribes count booty; deportees trudge away. A few panels show what happens to selected men who made the wrong call—pinned to stakes, flayed, or beheaded. You see the carrot and the stick in the same corridor. Sennacherib did not need to hang posters. He built a hallway that did the job.

Cruelty with an audience

Assyrian kings were not the first to execute rebels, but they turned punishment into stagecraft. The timing mattered. Executions often happened within sight of city walls or on the route used by deportees. The props mattered. Heads stacked in piles, skins hung on gates, stakes raised in lines—these are signs meant to be read from a distance. Even the decision to spare some groups served the message. Mercy looked like a royal gift, and gifts must be repaid with obedience.

There is a second audience: the Assyrian court. Reliefs flatter the king’s command of order. Captains keep ranks, engineers finish their ramps, scribes control the paperwork. The system works. That reassurance was part of the psychology, too. Fear outside; confidence inside.

Deportation as policy

Mass resettlement appears again and again in the art. It breaks rear-guard resistance. It creates mixed populations that cannot easily coordinate revolt. It also lets the king reward loyal allies with skilled labour moved from captured cities. Families march under guard, oxen pull carts of household goods, soldiers carry spears at intervals. The rhythm on the wall is deliberate: step, step, step—across the empire, across generations. For subject kings, the sight bites deeper than any execution. Lose, and it is not just your life. It is your people’s map that gets redrawn.

Crucially, deportation carried a promise. If you settled and paid, you could farm again under Assyrian protection. That mix—fear for the present, a usable future if you comply—kept tribute flowing.

Architecture that intimidates

Walk through the gates of Dur-Sharrukin or Nineveh and you pass under winged bulls with human heads, colossal lamassu carved with muscles and curls. They are beautiful, yes; they are also warnings. The threshold is guarded by more than soldiers. Inside, the first rooms narrow, then widen into long halls whose walls tell you what happens to fools. Architecture guides behaviour. It also compresses you into the king’s story before you meet the king.

The scale matters. Size is a message. Reliefs at human height draw you in; lamassu at multiple tons push you down. Either way, the body gets the point before the mind finishes the caption.

Royal boasts, crafted for effect

Annal entries are not diary scribbles. They are scripts. The formula repeats: the king sets out, lists cities stormed, names rulers who fled, notes how many chariots and horses were taken, and spells out punishments. The pattern is easy to remember and easy to retell. Scribes produced copies. Priests read them in temples. Officials kept them in archives for visiting rivals to find.

One record—on a famous hexagonal prism—delivers the line every petty king remembers: a rival “shut up like a caged bird.” The wording is ruthless and tidy. It leaves room for survival and humiliation in the same breath. As a phrase, it travels well. As a policy, it boxed rulers into choices they were meant to hate.

Mind games before a single arrow

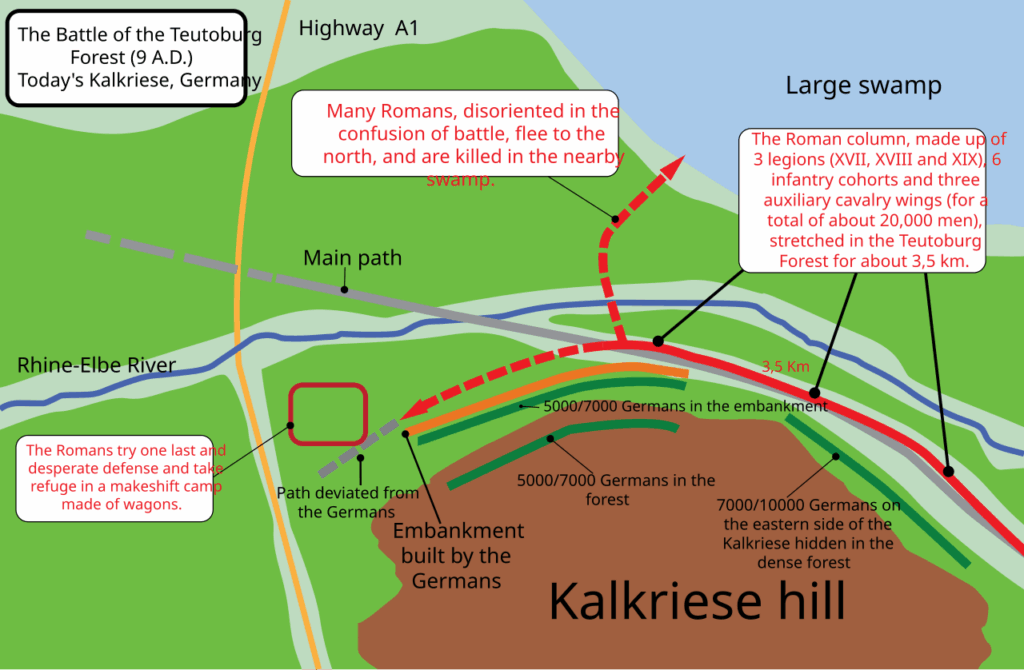

The Assyrian playbook starts long before the first siege tower rolls. Envoys arrive with letters and lists. They demand hostages and tribute. They recite what happened last year to cities with doubtful loyalty. They display exotic booty stripped from other kings. The message lands before the army does: we know your walls; we know your allies; we know your price. When the vanguard finally appears, nerves are already frayed.

Scouts and informants have done their work, too. Letters in cuneiform archives show the crown receiving field intelligence and asking for exact numbers of troops, horses, and rams. Psychological warfare is administrative. It is files and memoranda as much as drums and trumpets.

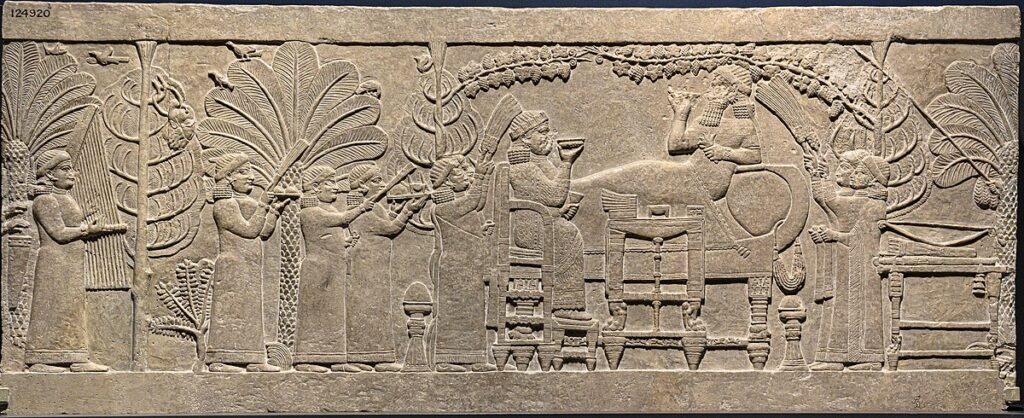

The spectacle of victory

Even banquets were propaganda. In one famous relief the king reclines with his queen beneath vines. A severed head dangles from a nearby tree—the head of an enemy king. Music plays. Attendants fan. The scene is leisure with a sharp edge: we are comfortable because our enemies are not. Anyone ushered into that room would understand without a single word from the throne.

Hunts work the same way. Lions charge; the king draws the bow and stands firm. The subtext is simple: if he tames the wild, he can tame you. Poetry and annals add gloss, but the relief does the heavy lifting. It is a silent sermon on power.

When terror fails

Psychological warfare is never total. Some cities hold; some coalitions form; some campaigns stall. Assyria knew setbacks and, eventually, collapse. But while it lasted, the mix of spectacle and punishment saved time and blood—Assyrian blood, at least. Cities that opened their gates avoided the worst. Those that wavered found themselves looking at stakes, ramps, and rams in the same dreadful frame.

The system demanded constant performance. New victories had to refresh the gallery; new annals had to update the boast. When the current king weakened, the spell faltered. Without fresh fear, the stories in the walls looked like history instead of the present. Enemies tested limits. The empire learned what every propagandist learns: you must keep the message moving.

Lessons that outlived an empire

Later states copied pieces of the Assyrian kit—monumental gateways, public inscriptions, staged victory parades, managed deportations, and idealised scenes of the ruler in control. They adjusted the cruelty for their own sensibilities, but they kept the structure. To rule a large territory with limited manpower, you persuade the many with what you do to a few. You show outcomes in advance. You tell the story of tomorrow today, loudly, in stone.

We often meet the Assyrians through biblical or classical passages that hate them. Yet the reliefs let the kings speak for themselves. The voice is chilling and clear: I defeated, I dismantled, I relocated, I rebuilt, I installed. A modern reader does not have to admire the voice to recognise how effective it was. That is the point of studying it. Techniques travel even when empires do not.

How to read the pictures

Stand close. Look for the details that carry the message. A prisoner’s hands clutching a child’s wrist. A scribe’s stylus resting at the line that counts captives. A soldier pausing to drink while a stake rises behind him. Then step back. The hall becomes the scene. You are walking through the city’s future if it says no.

Then find the exit and imagine being an envoy from a small hill town asked to wait for an audience in that space. Every slab you pass is an argument. By the time you bow, the answer may already be forming in your throat: “We will pay the tribute.” That moment—before you speak, when the mind has already moved—is where Assyrian psychological warfare lived.