Ask what made Hannibal’s legend so durable and you will hear about Trasimene’s fog, Cannae’s encirclement, and a column threading the high passes of the Alps. But the image that refuses to fade is simpler: a mahout perched behind a great ear, a goad in hand, and a massive grey shoulder pushing through the snow. Elephants gave Hannibal shock power, spectacle, and—perhaps most importantly—a reputation for doing the impossible. Yet the animals themselves were not myths. They were particular species, captured in particular places, trained with particular methods, and supported by a supply chain that had to work every single day or all the romance in the world would collapse in a heap of unwatered, unfed reality.

This is the story behind the spectacle: what kind of elephants Carthage actually fielded, how handlers made them battle-ready, and why the Romans eventually learned to blunt a weapon that once sent cavalry squadrons scattering. Along the way, we will meet a coin that shows a rider’s tools, a painting that made a generation believe, and a temple far to the south where Africa’s own elephant culture left its mark in stone.

Which elephants marched with Hannibal?

Older books often speak confidently of a “North African elephant,” smaller than the savanna giants further south and supposedly easier to manage. Modern zoology describes this animal as a now-vanished regional population or subspecies; numismatic and literary hints place it in the Maghreb and across the Nile’s upper reaches. What matters for Hannibal is practical: Carthage drew on elephants that were accessible by trade or capture, and those animals were African. They stood lower at the shoulder than their largest Indian cousins, but they were imposing, quick to rally a rout, and capable of shattering a nervous cavalry line with a single rush.

Did Carthage ever field Asian elephants? One name keeps the possibility alive: Surus, “the Syrian,” remembered as Hannibal’s favourite mount in Italy. The nickname suggests an animal acquired through eastern connections—perhaps a gift, a purchase, or a prize that ultimately reached the Barcid camps. If Surus truly came from Syria, he may have been an Asian elephant, larger in frame and longer in tusk than his African peers. Either way, Surus is remarkable for being singled out; the bulk of Hannibal’s force still came from Africa, even if a prestigious outlier trod beside them.

Species and size: what matters on a battlefield

Elephants are not interchangeable. African savanna types carry bigger ears and a taller shoulder; forest elephants are stockier, with straighter, thinner tusks; Asian elephants have a domed forehead and a different temperament under pressure. But size alone does not decide a battle. Visibility, nerve, footing, and training do. The historical record—especially when it turns on a single encounter—can be skewed by numbers, terrain, and luck. The Seleucid success with Asian elephants at one famous clash, for instance, owed as much to deployment and mass as it did to species. Far more often, the advantages that mattered were basic: whether the animal would hold a straight line when slingers worked the flanks; whether it trusted its handler enough to keep moving into a wall of noise; whether it could pick its way through mud without losing a shoe that it never wore.

In Hannibal’s hands, elephants were not blunt instruments. They were flexible tools: screens for skirmishers, wedges for breaking cavalry, and psychological weapons aimed at morale as much as flesh. To use them well required knowledge that could not be invented on the march. Carthage had that knowledge, and had it before Hannibal was born.

Where Carthage found its elephants

The Mediterranean did not breed elephants, but the routes into Africa reached deep. Carthaginian traders and allies moved along the coast and inland corridors. Kingdoms to the south and west captured or bought calves; hunters followed watering points and riverbanks before leading the young back to holding pens. To the east, along the Red Sea and into the Horn of Africa, royal hunts are recorded in inscriptions and echoed in temple scenes. Armies do not conjure elephants out of thin air. They inherit networks of capture, care, and training. Carthage lived within that network and, for a time, mastered it.

Coinage quietly confirms the point. Silver pieces struck for Carthaginian forces in Iberia show an elephant striding with a cloaked rider on its neck, goad in hand. The message is not subtle: we have these animals, we know how to direct them, and we will bring them to your gates if need be. Numismatics is never neutral propaganda. It reflects what an issuer wants remembered and what an audience already understands.

How do you train a two-ton soldier?

Begin long before a battle. Calves captured young learn human voices, smells, and hands. The first months are routine: feeding, grooming, and touch without fear. A handler’s tools are simple—voice, stick, and food—backed by time. Once trust is set, cues come next: move, kneel, turn, back. None of it is magic. It is repetition layered on patience. The rider’s position, forward of the shoulders, matters; from there the handler’s weight shifts and taps communicate through the neck muscles with surprising precision.

After cues, distractions. Cloths flutter; horns blare; boys rattle bronze in skins. A good elephant must learn that din is not danger. Trained animals then work in pairs and files, because a column holds its nerve better when each beast can see the next one staying calm. Only after months of this do the dangerous lessons begin: how to push through wicker screens, how to lift a man with a tusk and toss him, how to step over a trench without breaking stride. Armour—if fitted at all—stays light; thick hides are armour enough, and heat is always the enemy.

Handlers, commands, and the little details that matter

Who taught Carthaginian elephants these habits? The inscriptions do not give us names, but the coin’s rider with a goad and cloak looks like any professional mahout: compact, balanced, and steady. The vocabulary of commands may have varied by region, yet the grammar—short vocal cues, reinforced by taps—stays recognisable from India to North Africa. Group drills create an instinct to keep alignment even when the air is full of missiles. If the animal bolts, the best answer is often another elephant drawn alongside, shoulder to shoulder, so that the pair steadies by contact and returns to the lane set for them.

Food and water are the real constraints. An army can skimp on comfort; an elephant cannot. Routes had to hug rivers or known springs. Grass, browse, and grain were gathered from nearby estates, with foragers riding ahead to buy, barter, or seize. The beast that makes a Roman cavalry horse rear at the sight will, in turn, turn sulky if a handler lets it go thirsty. Logistics often decides what tactics merely suggest.

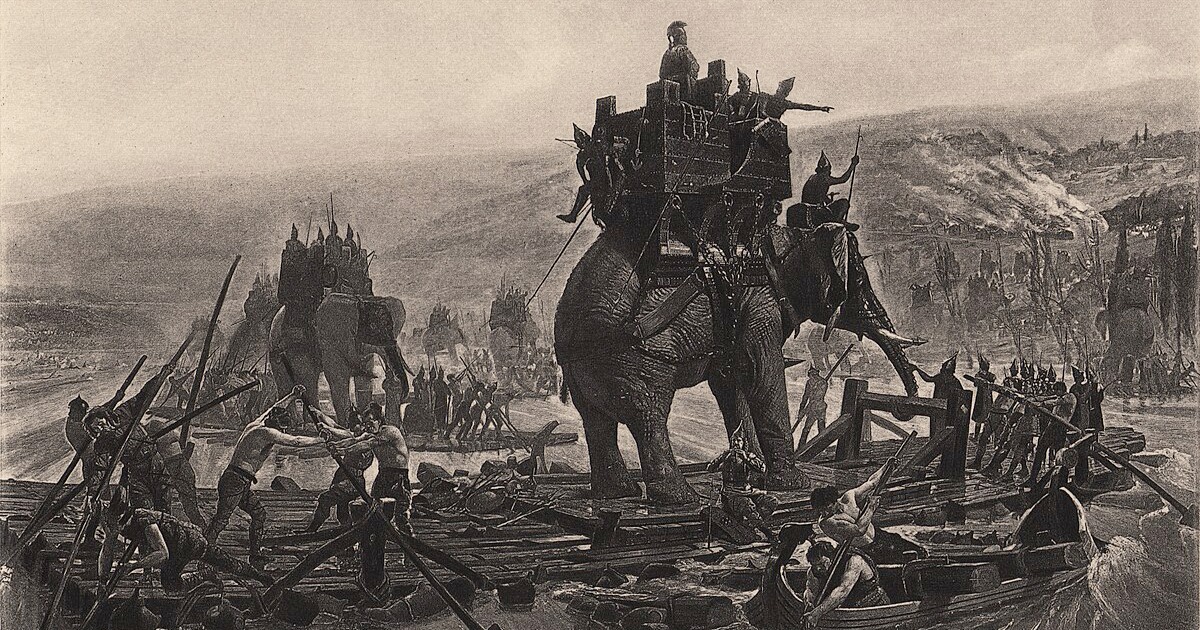

Across rivers and over mountains

Stories of floating elephants on rafts sound like tall tales until you remember how buoyant an elephant is and how calmly a trained animal can be coaxed into water. There are several ways to manage a crossing. One is to rig pontoons with earth on top so that a skittish beast believes it is still on land as it walks. Another is to swim them alongside boats with ropes to guide and rest them. None of this is easy; all of it is possible if you have handlers the animals trust. On mountain tracks, the trick is spacing, not speed. Hooves do better than a casual observer would expect, but ice is unforgiving, and one panicked elephant can knock three more off their feet. That Hannibal brought any across those passes says more about his staff work than about their appetite for heroics.

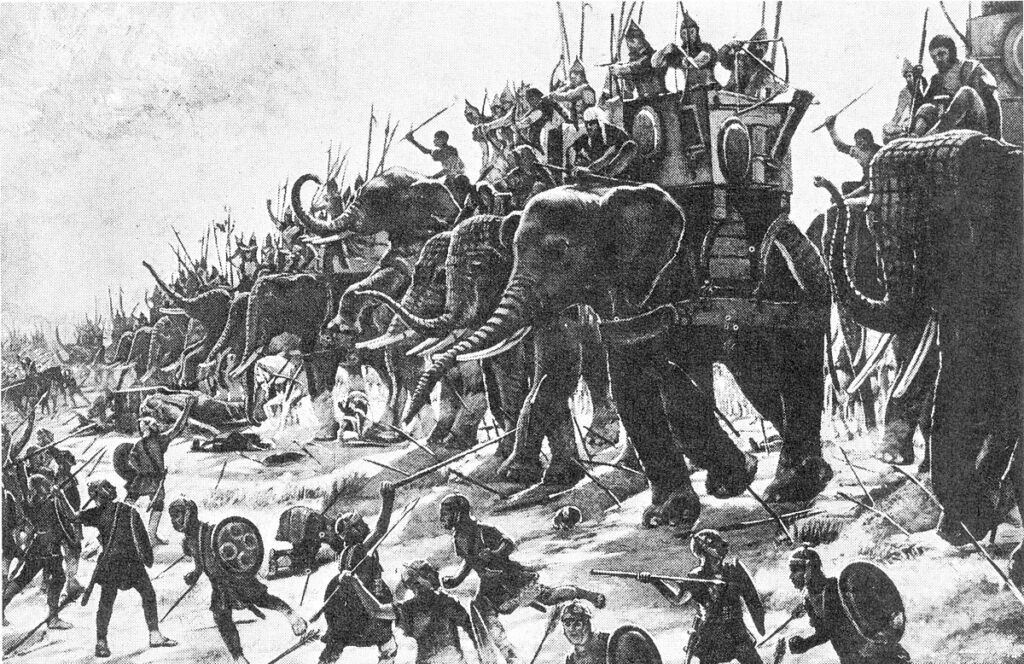

What elephants actually did in battle

On their best days, elephants were a cavalry problem first. Horses unused to their smell and bulk balk, wheel, and bolt. Hannibal knew this and drove his animals at Roman horse to tear open the flanks before the infantry lines fully bit. Against raw troops, a close thunder of feet and the rattle of howdah bells could be enough. Against veterans, the trick was to threaten and screen at once—keeping skirmishers busy behind the moving wall while javelins and slingstones probed gaps.

Roman answers improved with time. Skirmishers learned to target eyes and the soft skin behind the foreleg. Trumpets and horns blared to disorient. Manipular lines opened lanes at the last moment so that elephants, presented with a gap, rushed along it rather than into shields. Once through, men with hooks and blades followed to hamstring or isolate. At Zama, those practices mattered: much of the damage elephants caused fell on Carthage’s own rear as frightened beasts careened back into their support. It was not that elephants had become useless; it was that the Romans had learned.

Why the species question still matters

If you care about tactics, you might shrug. A tonne of momentum is a tonne of momentum. Yet the choice of animal shapes training time, water needs, and temperament under stress. It also ties Hannibal’s story into a broader African context. Elephants were not imports glued onto Mediterranean warfare; they belonged to an older, deeper tradition running through Nubia and the Kushite kingdoms. Reliefs and sanctuary walls in Sudan record a culture that knew these animals closely—hunting them, honouring them, and, at times, corralling them for human purposes. Set Hannibal against that backdrop and the Alps look less like a stunt and more like a daring extension of established practice.

Seeing the training hidden in the art

Look again at that campaign coin with the elephant and rider. The mahout sits forward on the neck, not high in a howdah; his right arm extends with a goad; the animal strides, not charges. This is a handler in control of a drilled mount, not a showman. When painters later imagined the great battles, they added thunderheads and rearing teams. The coin gives you something else: the quiet competence that makes thunder possible. On a wall relief from far to the south, elephants appear in processions of power where kings and gods share space. In both cases the detail that catches the eye is technique—the calm alignment of legs, the measured turn of a head, the way a rider’s weight centres over the spine. Art is documentary if you know where to look.

Why the Romans changed the terms

After the first shocks wore off, Rome brought cold discipline to an emotional problem. Officers wrote down what worked against elephants and drilled it. Engineers cut stakes and laid pits on likely approaches. Quartermasters learned to starve enemy beasts of calm by sending skirmishers to harass their foragers. The army that once scattered at the first sight of a trunk eventually led hamstrung animals in victory parades. Some were even turned to Roman use—not often, not always well, but enough to make the point that there is no monopoly on technique.

That change reveals something larger. Where an elephant charge had once been a hammer, it became a test. If you held your nerve, opened your lanes at the right moment, and let the fleshy wall thunder into the space you offered it, their power bled away. The moment commanders fully trusted their men to do this on command, the age of the Mediterranean war elephant had already begun to end.

Legacy and lessons

Hannibal’s elephants live on because they carry good stories. They also carry good lessons. First, logistics beats theatre. If you cannot feed and water an elephant, you do not have an elephant, you have a liability. Second, training defines the weapon. A column of nervous beasts is a hazard; a drilled file is a tool. Third, the enemy adapts. Rome did, and once it did, the value of the elephant slipped from necessary to situational. Even so, the animal left a stamp on tactics, art, coinage, and memory. A single silver piece with a tiny rider can make a case as eloquently as a room-sized canvas with rumbling clouds.

As for the species question, the neat answer does not exist, and that is fine. Carthage fought with the elephants it could get, mostly African, possibly with the occasional eastern outlier. The real wonder is not which exact skull shape loomed over the Roman lines, but that handlers could persuade any elephant to walk, calmly, into a hail of iron and noise—and that those who faced them could learn, in time, to stand still and let the storm pass through.