Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths is a flexible way to read Greek, Roman, Norse, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian stories without flattening their voices. Think of it as a toolkit of moves—call, crossing, trials, descent, ordeal, reward, return—rather than a rigid checklist. Used well, it helps you trace how communities turn disruption into meaning and private courage into public good.

Older scholarship sometimes treated the “monomyth” as a single universal pattern. That view is handy but risky. Greek epic is not Roman civic theology; Norse poetry is post-conversion and winter-haunted; Egyptian myth folds heroism into daily maintenance of Ma’at; Mesopotamian poetry turns loss into care for walls and people. This guide honours those differences while showing genuine overlaps you can use in teaching, research, and writing.

Below you’ll find clear stages, archetypes that travel well, cultural accents that change the rhythm, descent scenes that teach, and practical reading tools. You’ll also get object-based anchors—vases, reliefs, tablets—so the Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths stays tied to things you can actually see.

What the Hero’s Journey Is (and Isn’t)

The model names familiar steps: a call interrupts ordinary life; a threshold forces commitment; trials build skill; descent extracts truth; an ordeal tests it; reward and return spread the gain. But ancient evidence varies. Some heroes never come home. Others win by restraint, law, or speech rather than force. Treat the model as a vocabulary of moves, not a cage.

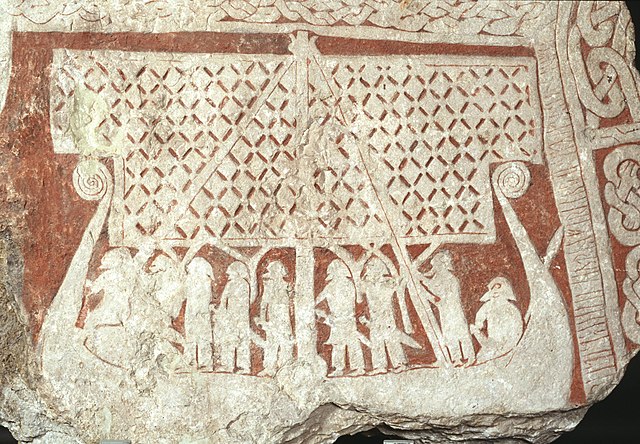

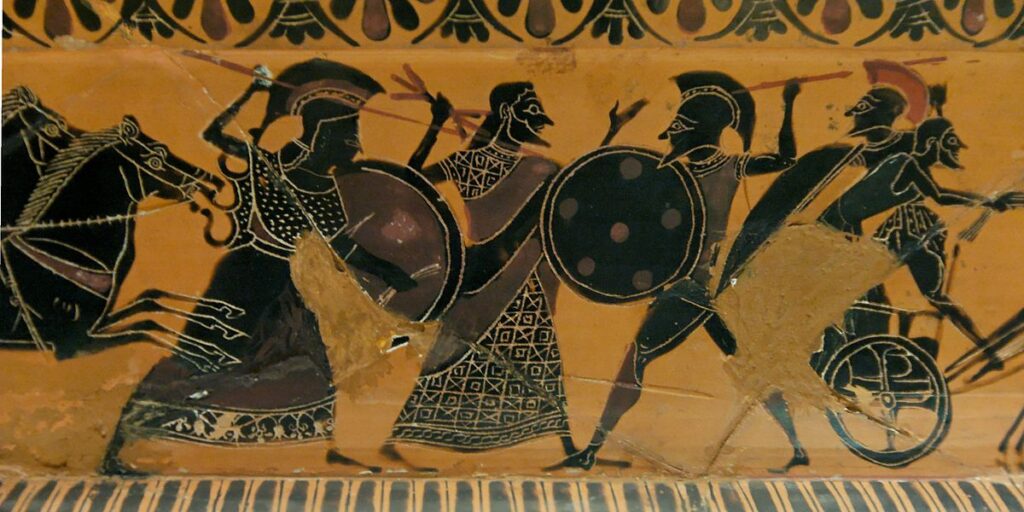

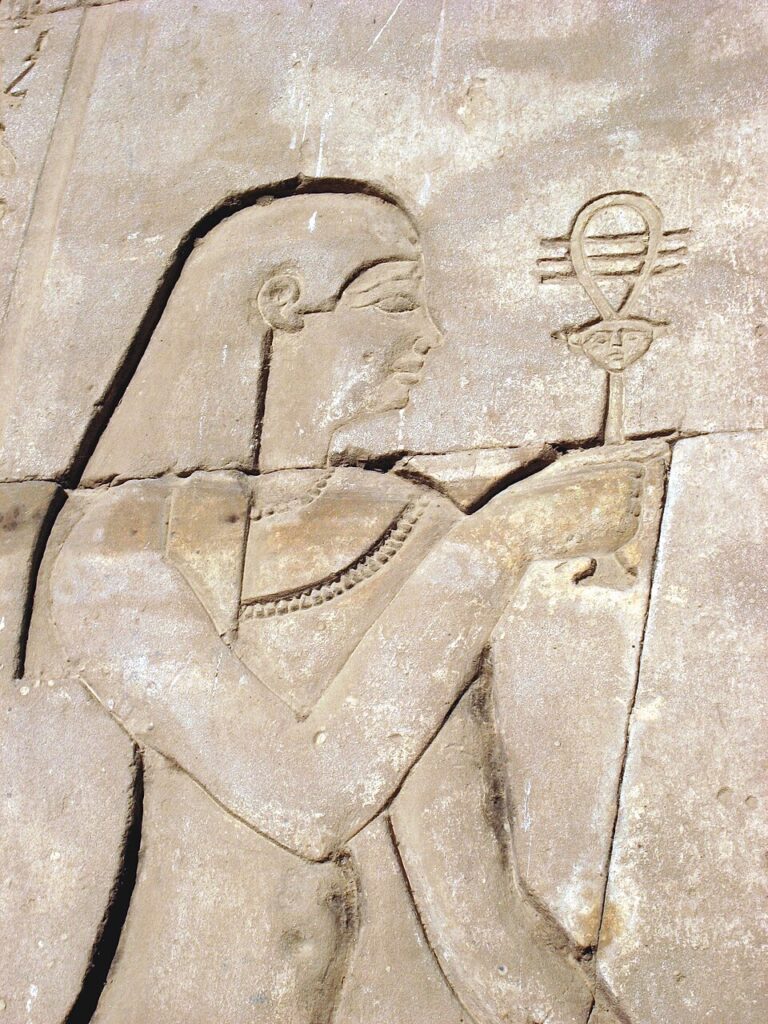

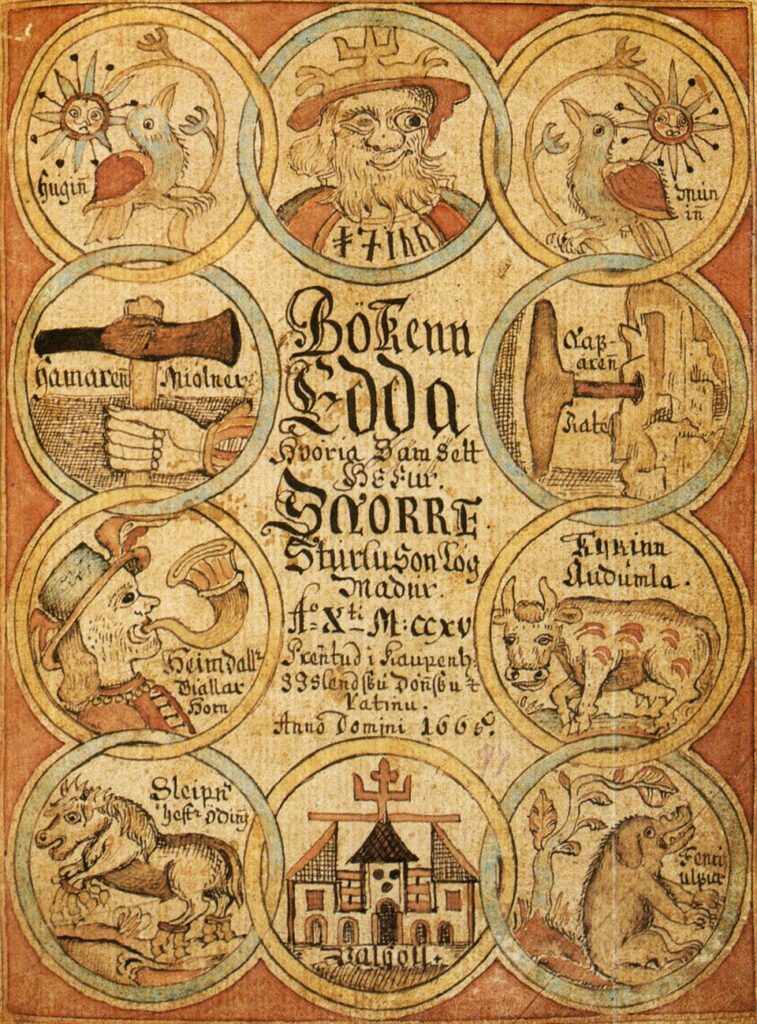

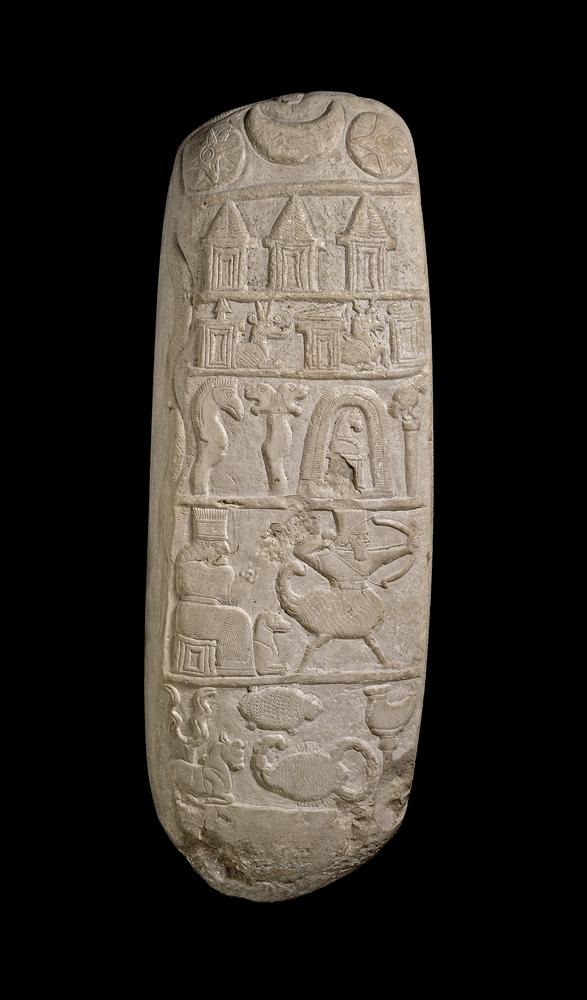

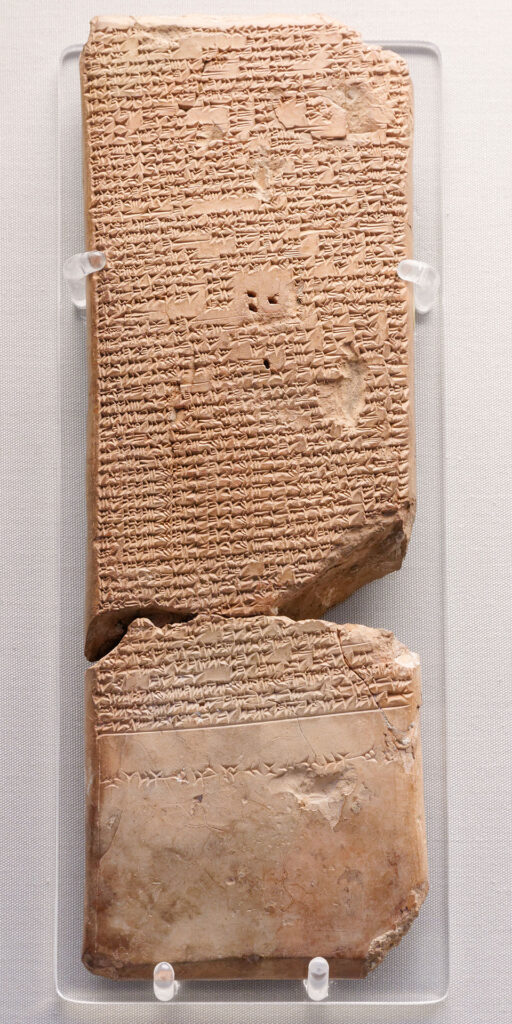

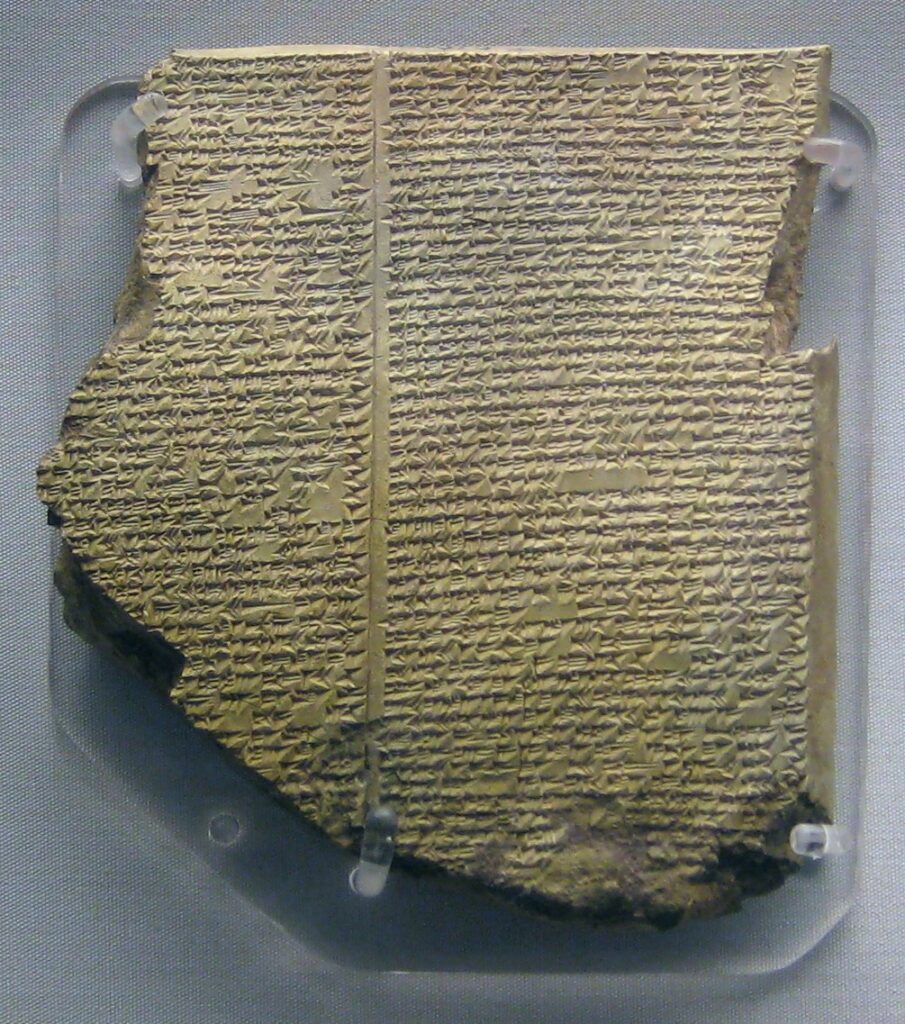

Sources to keep in view: Greek epic and tragedy, Roman epic and history, Norse Eddas and picture stones, Egyptian temple reliefs and funerary papyri, and Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets. Genre and date matter. When in doubt, start with the object or text, not with the pattern.

Core Stages Across Cultures

1) The call to adventure

The call names a public need. Theseus hears of a deadly tribute and sails for Crete. Aeneas flees Troy with father and household gods—duty packed into a bundle. Sigurd inherits a task knotted to a cursed hoard. Horus must restore lawful rule after Osiris’s murder. Gilgamesh, split open by grief, seeks limits. Calls in the Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths are more than dares; they summon service.

2) Thresholds and gatekeepers

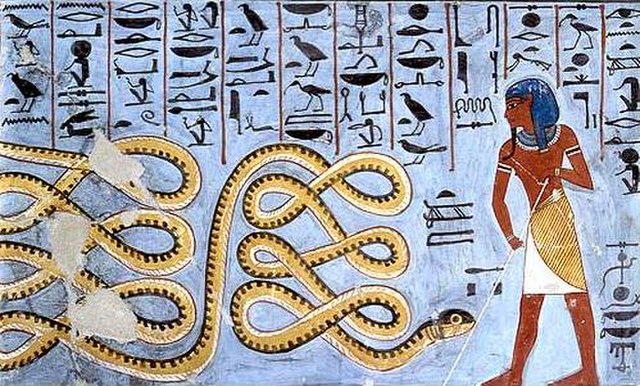

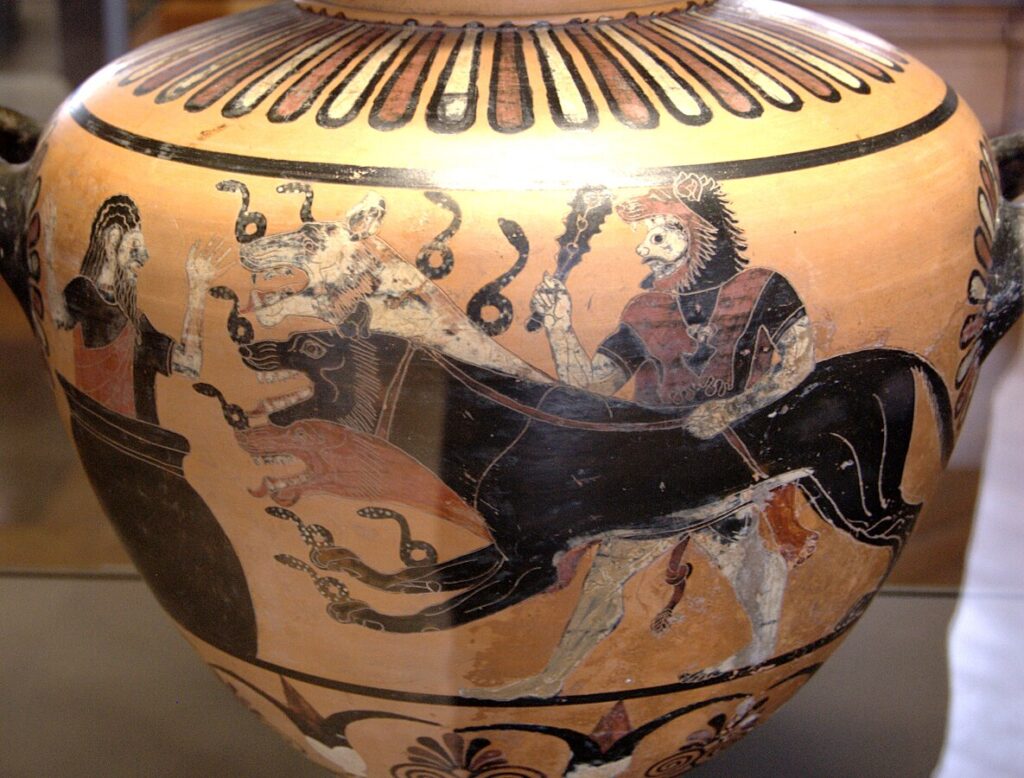

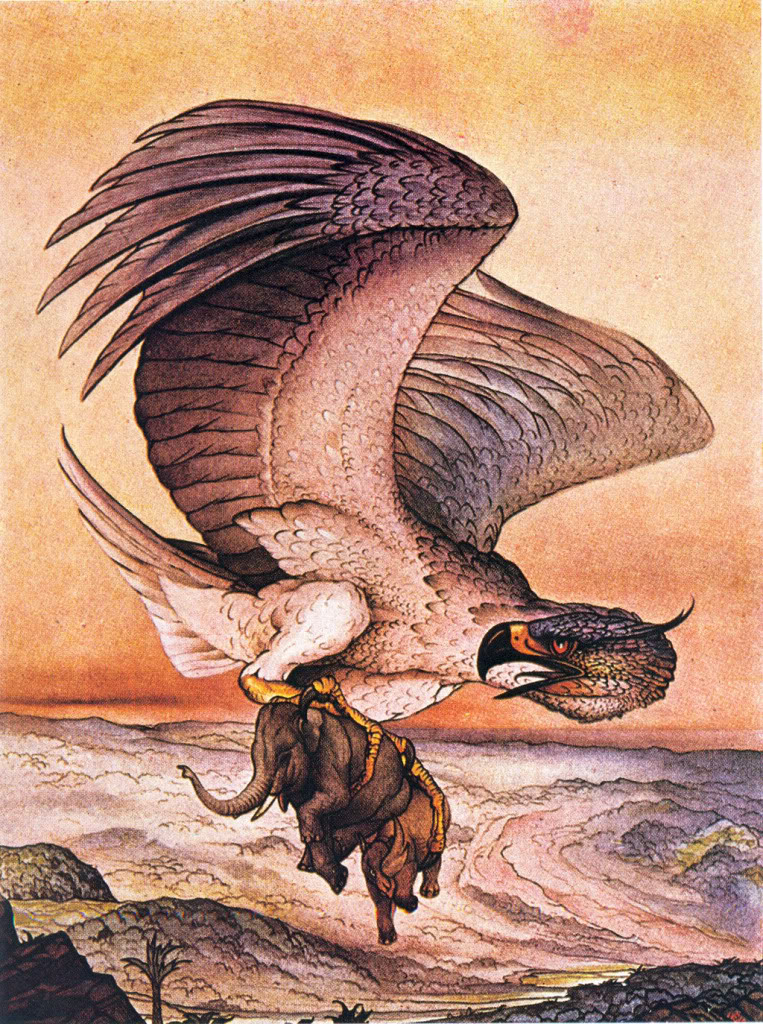

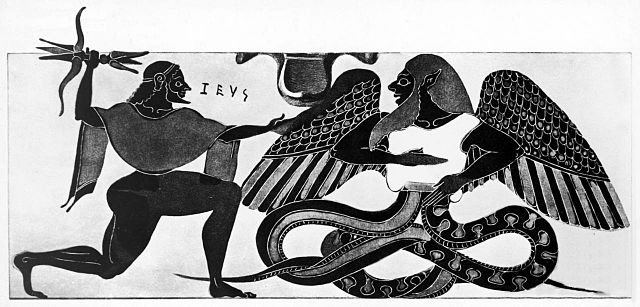

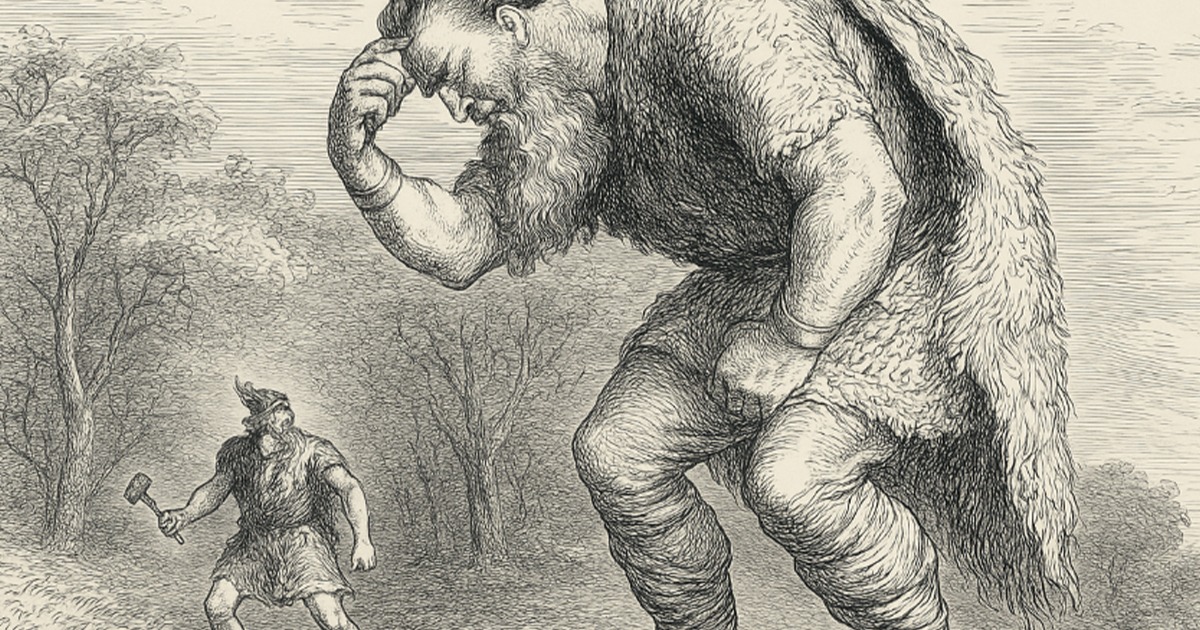

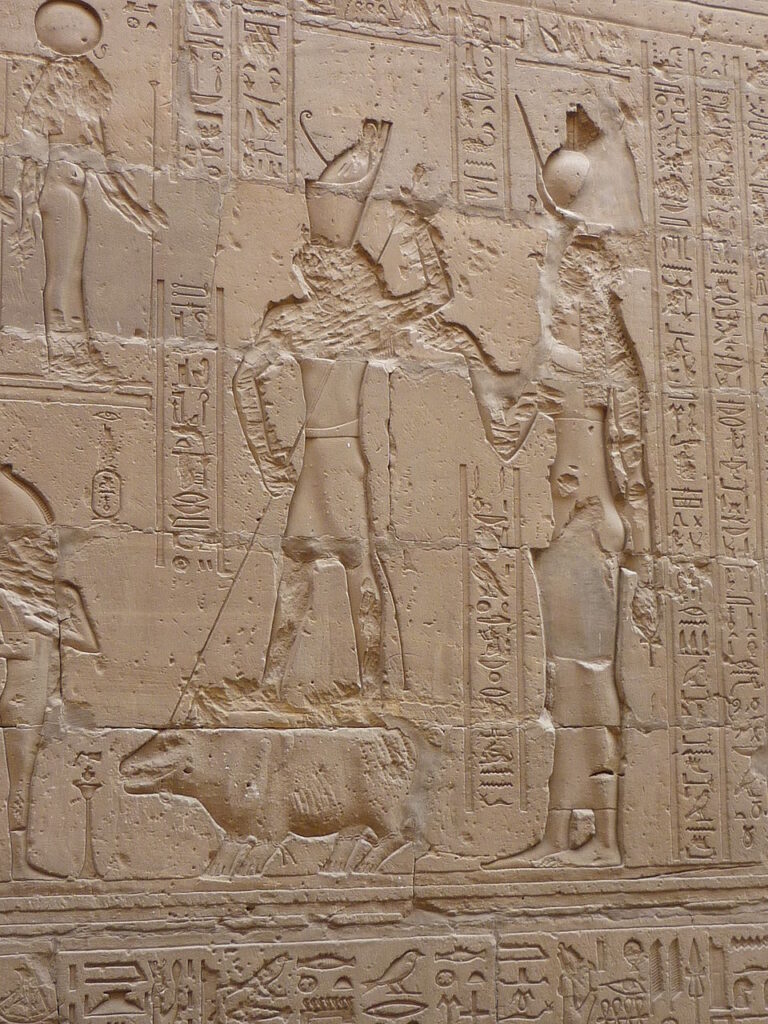

Crossing makes intention real. Odysseus meets winds, witches, and the sea’s slow tests. Norse heroes face geographies with teeth—fens, lairs, winter roads. At Edfu, Egyptian reliefs show Horus spearing Set-as-hippopotamus, a ritual threshold between chaos and order. Gatekeepers tempt, judge, or simply wait at the door to test fitness.

3) Trials, helpers, and tools

Trials shape skill and character. Helpers arrive with gifts or counsel: Athena’s steady advice, Ariadne’s thread, a smith’s blade, a true name that opens a gate. Roman stories weigh pietas—duty to family and gods—so Aeneas’s “tools” include ancestors and household cults. Egyptian spells and names work like passports. Each helper reveals how a culture believes power should grow: by learning, loyalty, sacrifice, or sacred knowledge.

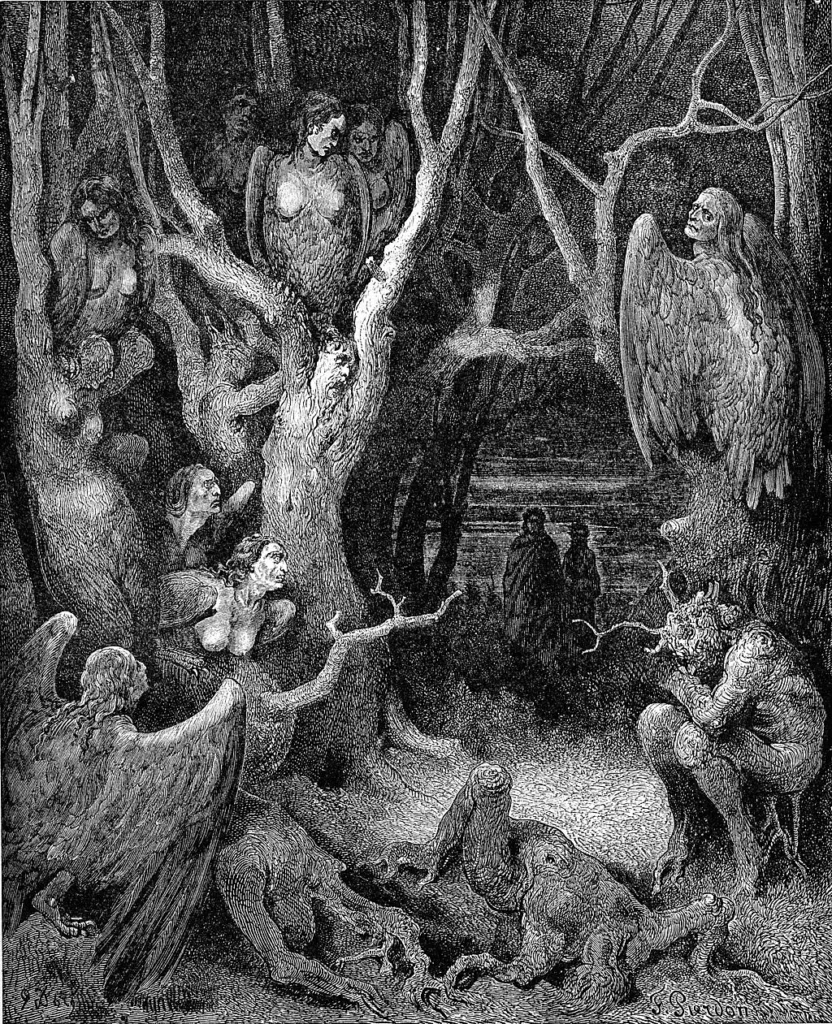

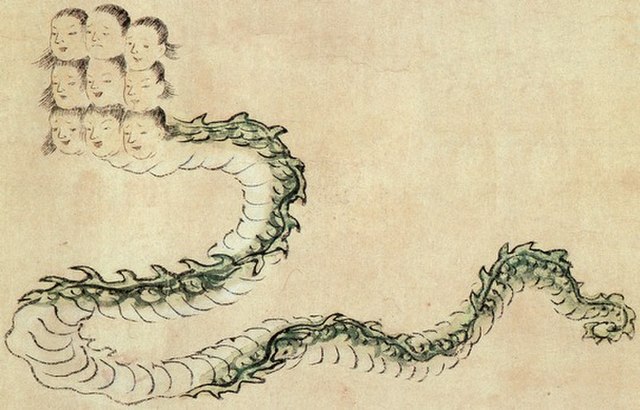

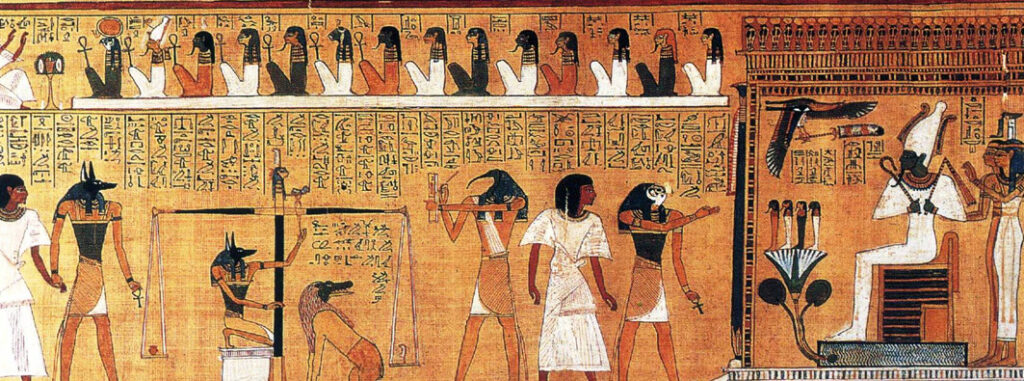

4) Descent to the underworld

Descent teaches what weapons cannot. Odysseus seeks counsel from shades; Aeneas learns the weight of Rome’s future; Egyptian judgement scenes weigh the heart; Norse endings turn descent into preparation for a brave stand. In the Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths, the underworld is where fear becomes clarity.

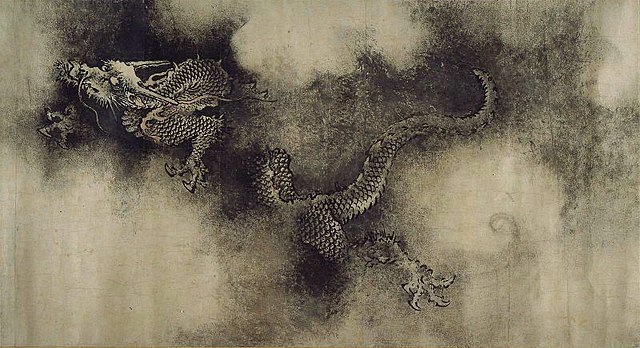

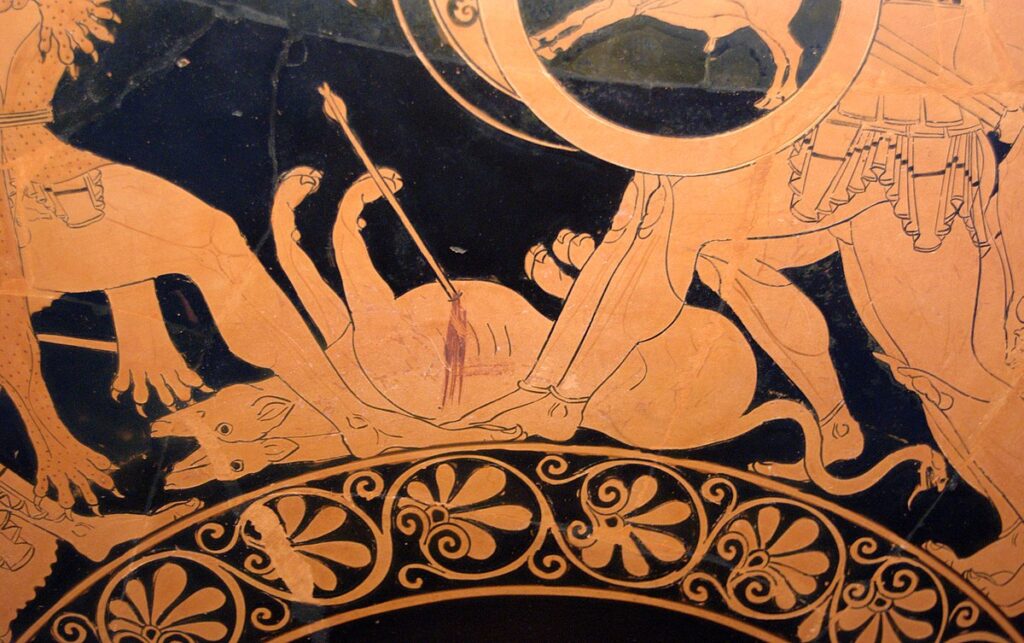

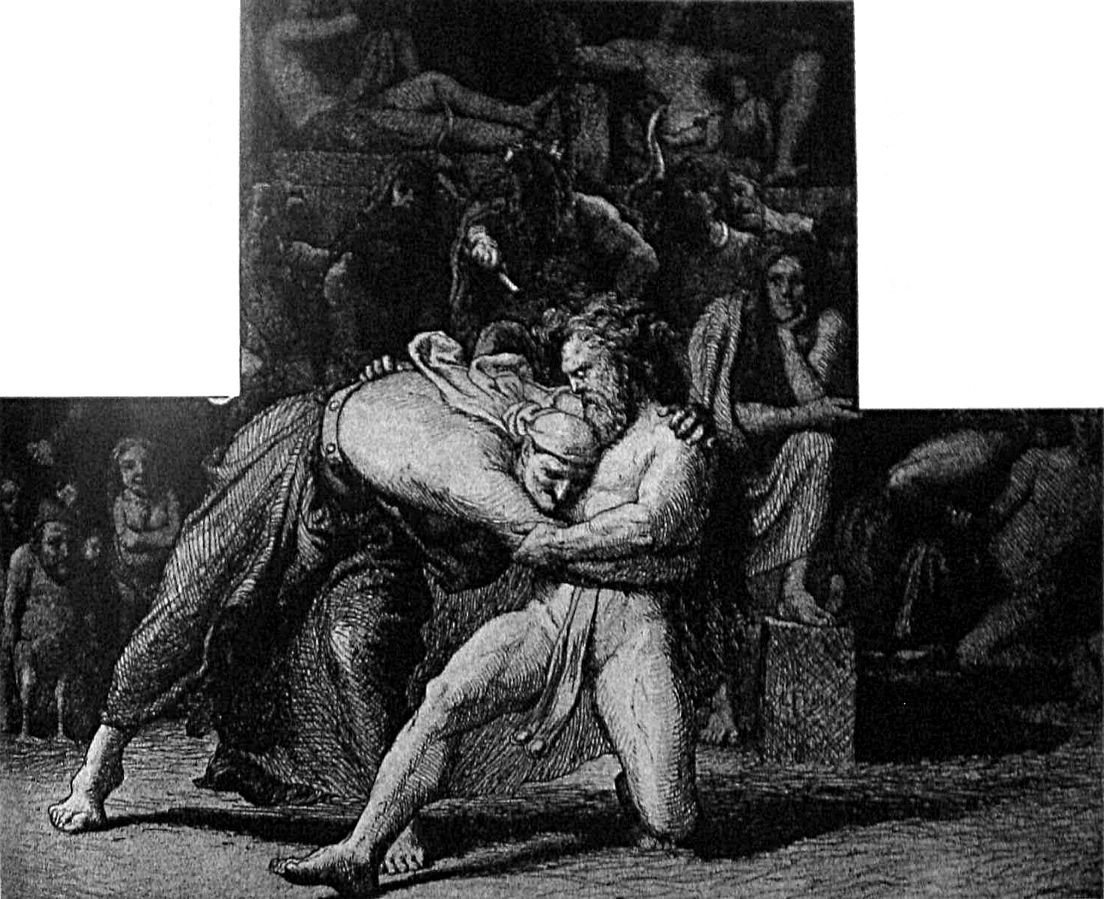

5) Ordeal and recognition

After descent, the ordeal makes insight concrete. Theseus meets the Minotaur in close quarters. Sigurd kills a dragon and learns dangerous speech. Horus proves rightful rule against a clever rival. Gilgamesh meets mortal limit. Recognition follows—by the world, and by the hero. Change is visible and costly.

6) Reward, return, and change

Rewards vary: a city, a lawful throne, knowledge, seasonal balance. Some stories return home; others return with a mission. Roman cycles bend toward founding; Egyptian cycles restore Ma’at; Norse cycles heighten courage within fate. In every case, return tests whether the new self can serve the community that sent the hero out.

Archetypes That Travel Well

The hero

The hero accepts a burden others refuse. Herakles shoulders unglamorous labour. Aeneas carries his father. Sigurd listens when birds speak. Horus embodies rightful succession. Strength matters; so do patience, loyalty, and judgement. In the Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths, the hero is the one who keeps going for others.

The mentor

Mentors turn talent into durable skill. Athena advises without stealing agency. Roman elders model pietas. Norse mentors pay for knowledge, so advice feels earned. Egyptian guides teach names and forms that guard against chaos. Good mentors hand over tools, not orders.

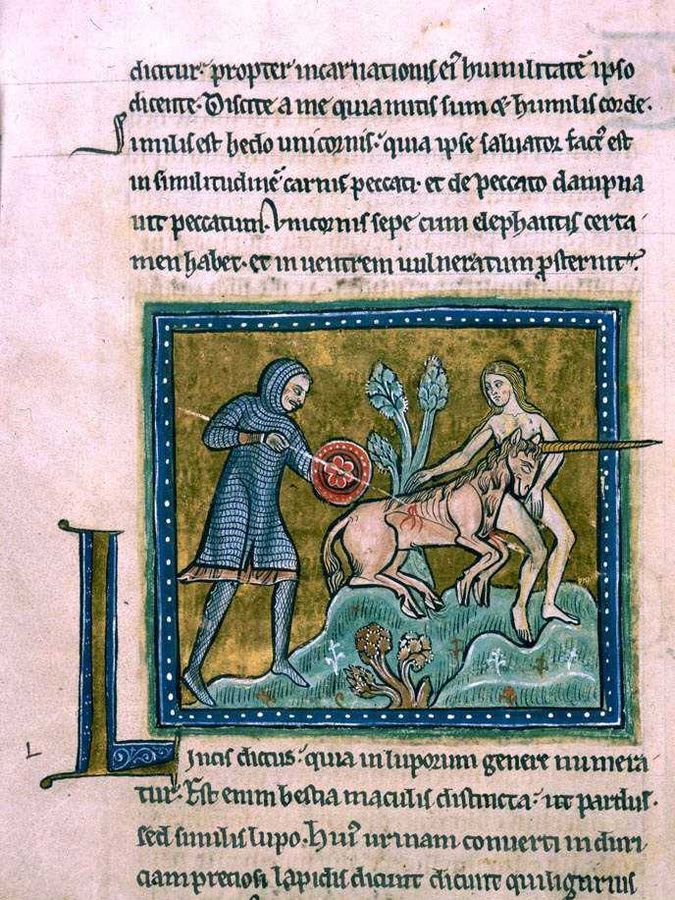

Threshold guardians

Gatekeepers test truth, courage, and proportion. Sirens tempt; Minotaur threatens; Set litigates and fights. Guardians make sure the journey belongs to someone ready for risk with measure.

Shapeshifters and tricksters

Changeable figures stress-test values. Medea’s help complicates success. Loki’s wit exposes brittle pride. Egyptian magic serves intent—good or ill. Tricksters force heroes to choose with care.

The shadow

The shadow is an enemy and a mirror: hubris, despair, hunger for power. The best fights are inward as well as outward. Conquering the mirror matters as much as surviving the day.

The ally and the herald

Allies make the work possible—loyal crews, faithful friends, households that hold steady. Heralds bring the call: omens, messengers, dreams, signs. Together they move a private wish into public duty.

How Cultures Shape the Cycle

Greek and Roman frames

Greek stories prize excellence within limits; hubris brings ruin because it denies scale. Trials often test measure and intelligence, not just force. Roman stories bend the arc toward duty and founding. Aeneas is brave, but the lasting image is burden and care. The Roman Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths reads as public service shaped by law and memory.

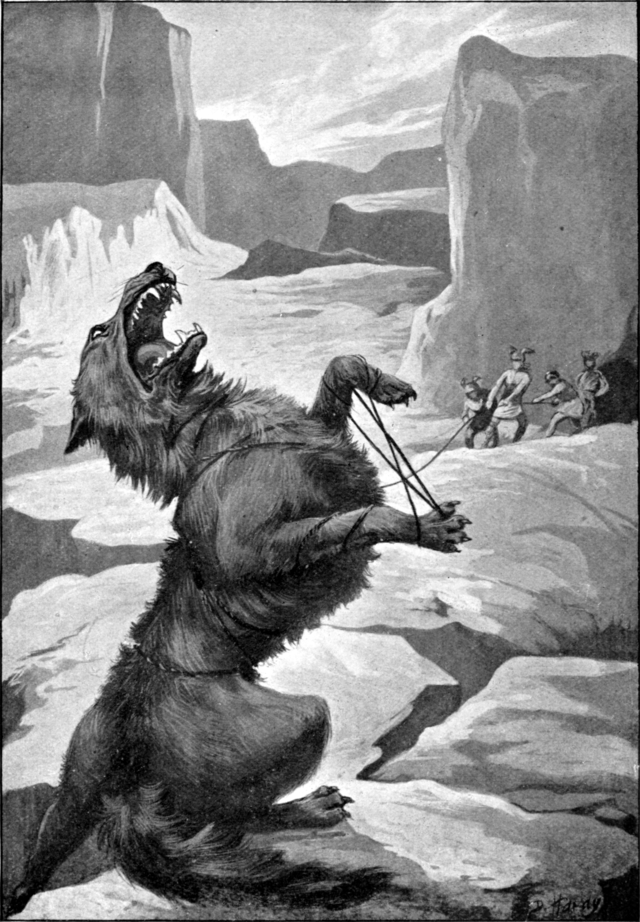

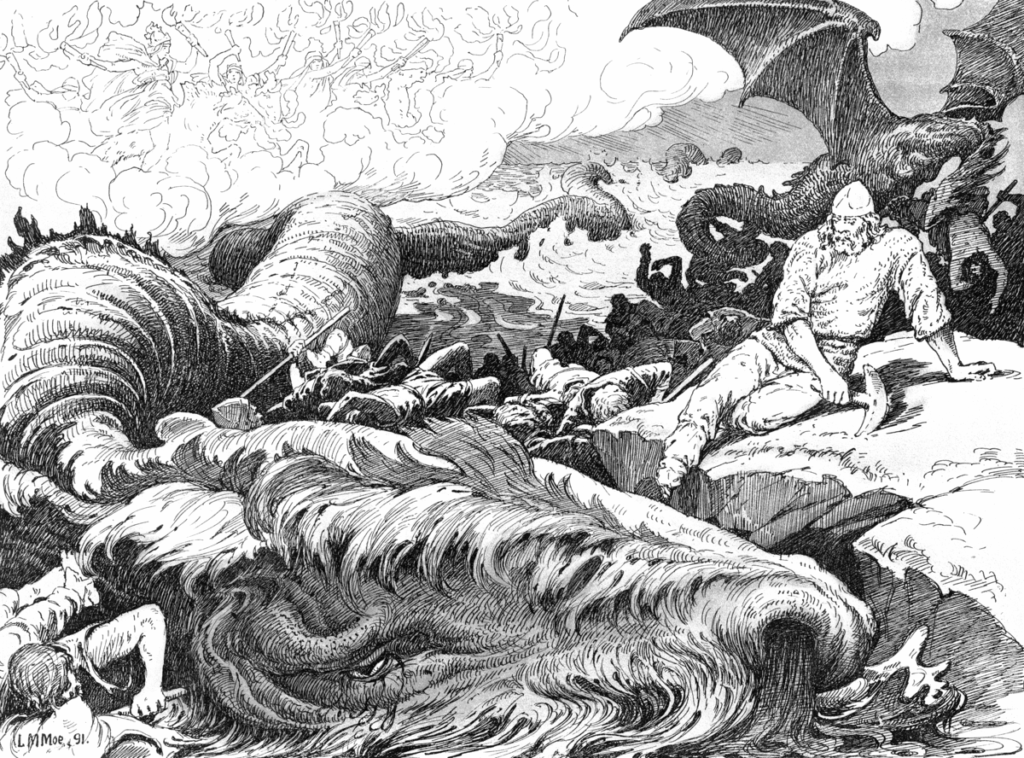

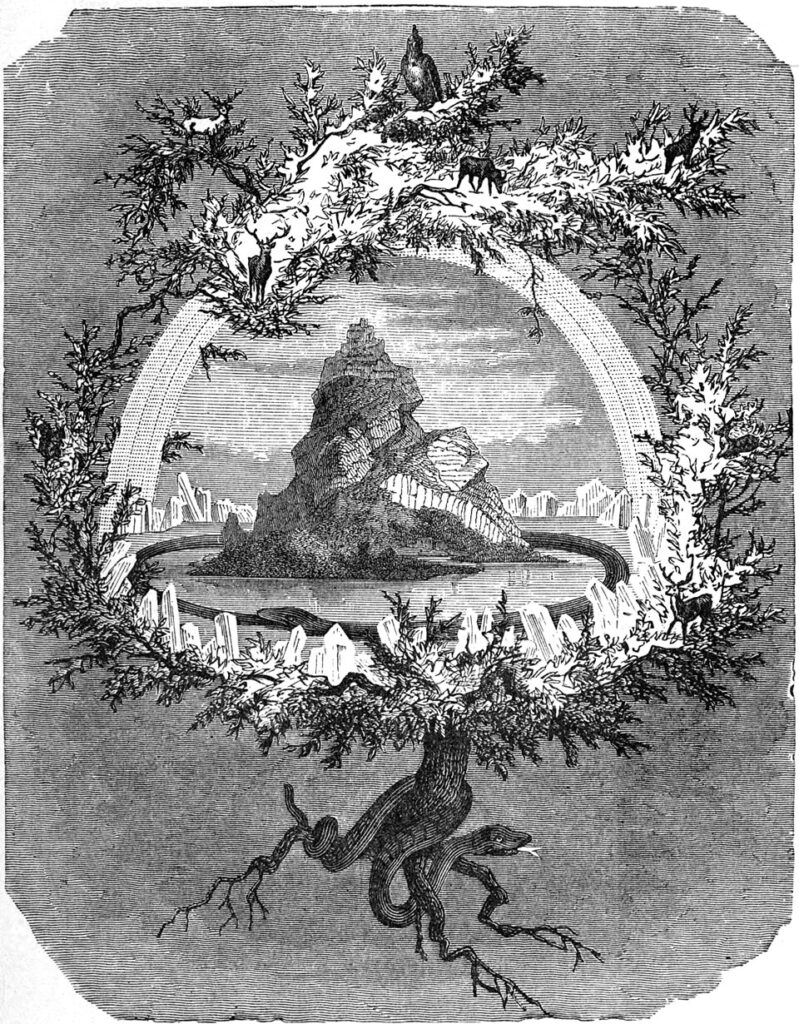

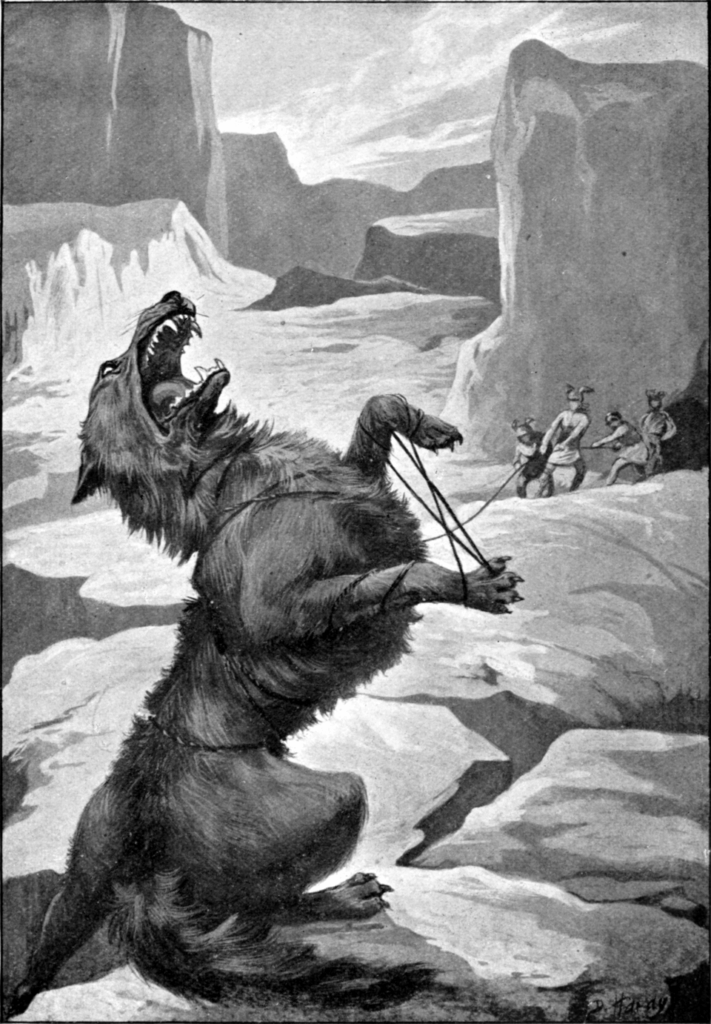

Norse textures

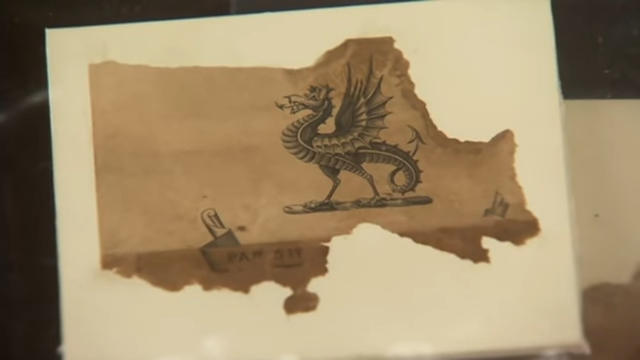

Norse material lives with risk. Winter and feud sit close. Trials feel like holding a line more than conquering forever. Knowledge is costly; courage endures; fate sets boundaries even gods respect. That tone gives Norse journeys a stern beauty and a pedagogy of steadiness.

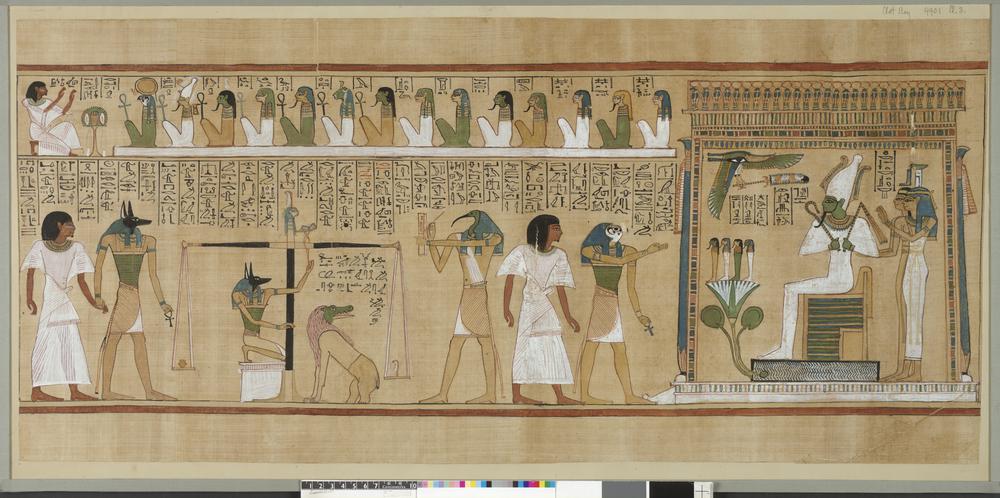

Egyptian logic

Egyptian myth locates heroism inside daily maintenance of balance. Horus versus Set is a fight and a lawsuit. Priests and kings renew order with precise acts. Reward is Ma’at restored, not private glory. The cycle is seasonal: the sun rises, the Nile floods, ritual repeats with meaning.

Mesopotamian depth

Gilgamesh widens the cycle into a search for limits. The call is grief; the trials are friendship and monsters; the descent meets a flood survivor; the return accepts mortal time and cherishes city and walls. It’s a civic ending with private wisdom, surprisingly modern in its tenderness.

License: CC0.

Descent Scenes That Teach

Descent gathers truth with a cost. Odysseus hears blunt warnings from the dead. Aeneas sees his people’s future and the grief it contains. Egyptian hearts meet a scale, turning ethics into a picture anyone can grasp. Norse tales look straight at endings and ask for steadiness. These scenes persist because they face fear rather than decorate it.

License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Motifs You Can Track Quickly

- The helpful gift: thread, sandals, true name, enchanted blade. Gifts carry obligations—service, silence, gratitude.

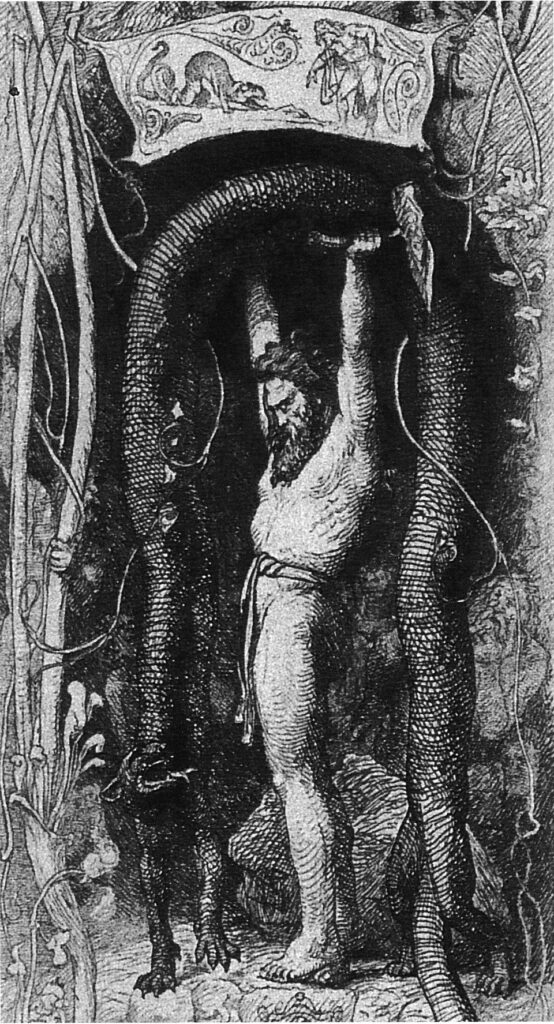

- The binding: Odysseus tied to the mast—discipline over appetite; oaths that bind warriors; vows that shape returns.

- The centre beast: a problem made flesh—lawlessness, famine, grief—rather than pure evil. Kill the beast and you still must repair the world around it.

- The return gate: re-entry tests whether the hero can live well at home and teach without pride.

- The name: knowing a true name changes the map—Egyptian spells, Norse runes, Greek divine epithets.

- The wound: a scar that marks cost and memory—Odysseus’s thigh, Sigurd’s hard knowledge, cities rebuilt on ashes.

Travel, Tools, and Geography

Geography writes structure. Island chains make looping sea-journeys with pauses for counsel and temptation. River plains build cycles that mirror flood and sowing. Mountain frontiers write marches, sieges, and winters. Tools matter too: a ship enables community on the move; a legal scroll solves a different problem than a sword; a ritual formula quiets panic better than a boast. Watch gear and map and you’ll predict the next scene before it arrives.

Case Snapshots

Theseus and the Labyrinth

Call: end a cruel tribute. Threshold: foreign court and maze. Helper: Ariadne with thread. Ordeal: close work in tight turns. Reward: lives freed. Return: complicated costs—guilt, abandonment, civic memory. The pattern pairs courage with craft and warns that success still needs wisdom.

License: CC BY 2.5 (Marie-Lan Nguyen/BM).

Odysseus and the long sail home

Call: war’s end. Threshold: a perilous sea. Trials: monsters, islands, a home full of threats. Descent: counsel among the dead. Ordeal: justice in the hall. Reward: a house set in order. Return: restraint crowned with mercy as the cycle closes on a bed built into a tree.

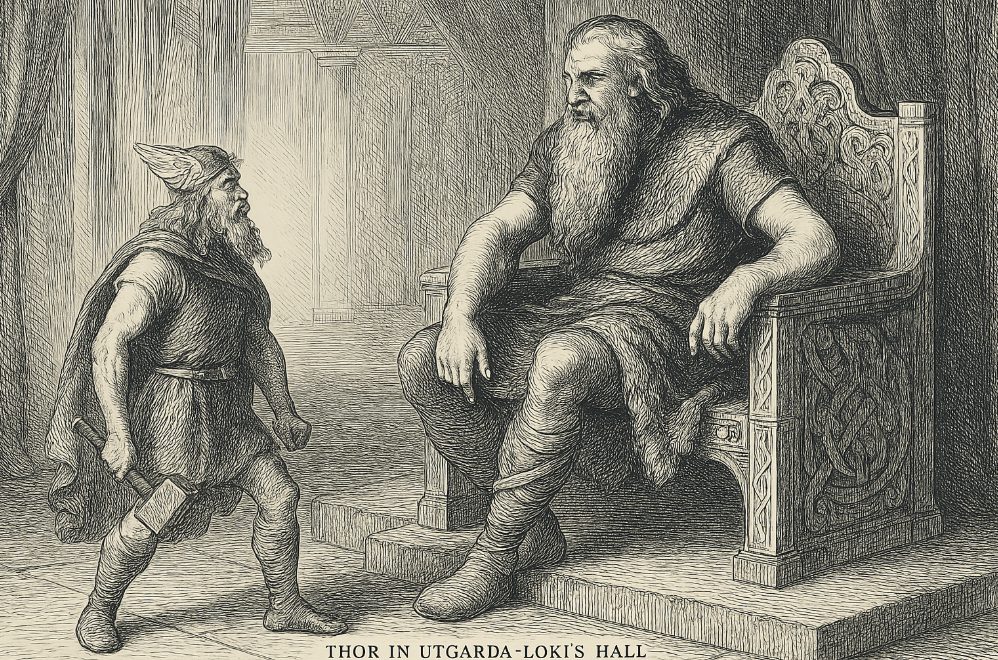

Sigurd and the dragon

Call: oath and obligation. Threshold: a lair that demands nerve. Helper: smith and counsellor. Ordeal: the kill that changes the killer. Reward: treasure and truth that burns. Return: fragile; knowledge weighs families down. Lesson: power without wise speech ruins households.

License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Horus and rightful rule

Call: restore order after a royal murder. Threshold: court and combat. Helper: Isis—care and skill. Ordeal: a rival who is clever and strong. Reward: legitimate kingship. Return: the land steadied. The Egyptian journey blends battle with justice, aligning personal victory with public balance.

Aeneas and the burden of founding

Call: Troy burns. Threshold: sea, storms, foreign shores. Helper: elders and gods. Descent: a tour of truth that sets a civic aim. Ordeal: war in Italy. Reward: a future people. Return: not to old walls, but to a new duty. Roman journeys turn courage into institutions.

License: CC0.

Women and the Journey

Women are not only prizes or portents; they are mentors, judges, guides, and heroes. Isis models patient, expert care that stabilises a kingdom. Ariadne’s thread is not decoration; it is engineering. Penelope’s weaving is strategy under siege. In Roman literature, women’s counsel often sets the ethical temperature. Norse Völur speak fate; communities listen. If you track the Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths without counting women’s labour, you will miss how success actually happens.

Non-Linear, Failed, and Anti-Hero Journeys

Not every arc returns cleanly. Some end in loss that teaches communities what to repair. Others spiral—revisiting calls and thresholds as families or cities learn the same lesson at higher stakes. Anti-heroes expose a culture’s fault lines: ambition without measure, power without service, knowledge without humility. Reading these “failed” journeys with care keeps the model honest and the moral world recognisable.

Influence and Practical Uses Today

Modern storytellers echo these moves because audiences recognise the rhythm. Teachers use the cycle to compare texts in a week. Curators map gallery routes from call to return. Writers outline with it, then vary the tune to fit their setting. The trick is simple: keep the heart of the pattern and the grain of each culture. Together they make durable work.

Related reading on this site: Nergal and Ereshkigal: The Mesopotamian Underworld Power Couple · Neanderthal Medicine Rediscovered · Fayum Mummy Portraits · Comparative Mythology: Greek, Roman, Norse, Egyptian.

Primary sources online: Browse the British Museum collection and The Met’s Open Access collection for objects that anchor these episodes.

FAQ

Is the Hero’s Journey the same in every culture?

No. The skeleton repeats; the muscles and skin differ. Each tradition tunes the cycle to local law, weather, and work.

Why do so many heroes descend to the underworld?

Because wisdom often requires looking at endings, not only hopes. Descent scenes turn fear into clarity, and choices improve after that.

Can a journey fail and still matter?

Yes. Failure can teach a community what to repair and how to carry grief together. Many ancient endings are useful for that reason.

How do I use the model without flattening stories?

Start with the source, map the structure, then compare. That order protects difference while revealing real patterns in the Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths.