Most readers meet the Epic of Gilgamesh through its central arc — the friendship with Enkidu, the defeat of Humbaba, the death that shatters the king’s confidence, and the long, hard search for immortality. But tucked at the far edge of the tradition is another piece, often labelled Tablet XII. It reads differently. Its tone is quieter, its plot stranger, and its place in the sequence is debated. Here the hero is not chasing everlasting life. He is trying to recover something small yet dear: a drum and drumstick lost to the underworld.

On the surface, it is a side story. Underneath, it is one of the clearest windows into Mesopotamian ideas about the land of the dead, the rules that bind it, and the thin, dangerous line between the living and those who have gone below. That makes Tablet XII both an oddity and a key, linking the famous episodes with older Sumerian tales and reminding us that epics are never static. They absorb, adapt, and carry pieces of the past forward in new frames.

Why it feels different from the rest

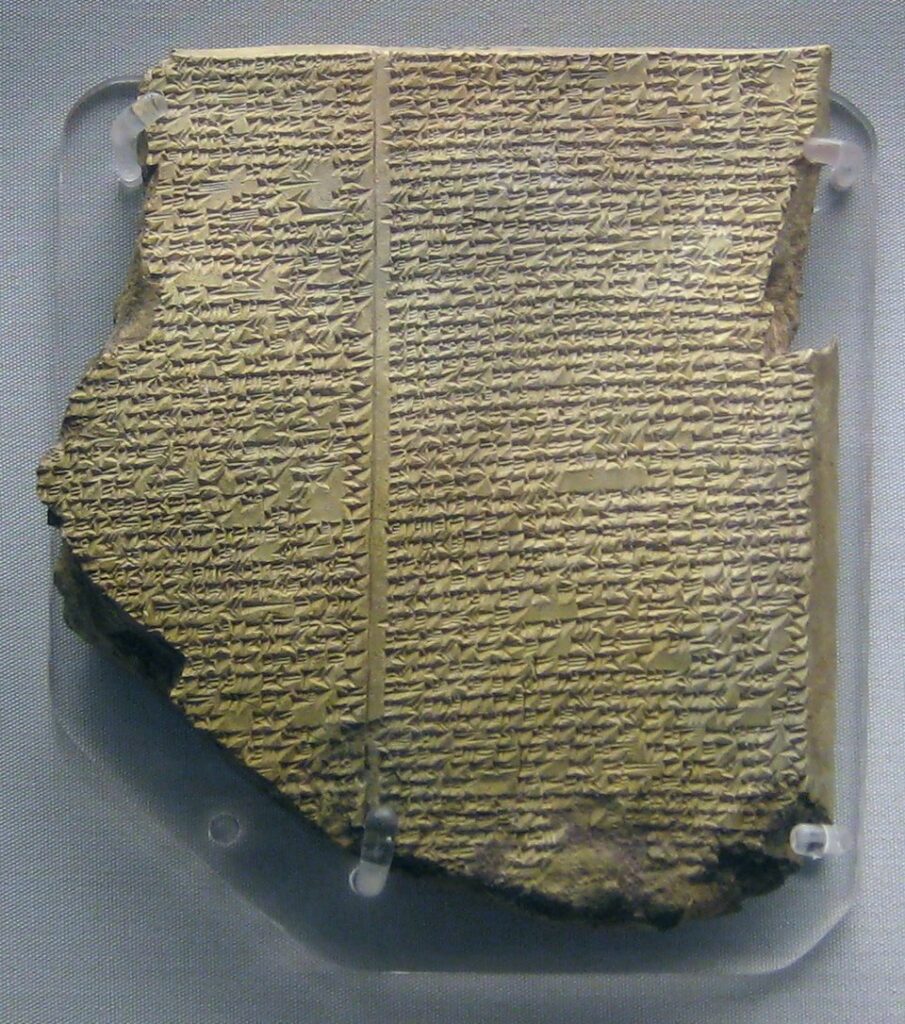

The main body of the epic comes from Akkadian compositions, blended and edited over centuries into a more or less continuous twelve-tablet cycle. The twelfth, however, is widely believed to be a later addition. It reworks a Sumerian story known as “Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld,” translating it into Akkadian while keeping much of its older shape. The language is more direct, the scenes less ornate, and the moral less tied to royal destiny. Scholars have long debated whether it was meant as an epilogue, a supplement, or simply an extra tale bound into the same set of tablets.

For readers, this difference is part of the charm. It opens a door onto the workshop where scribes linked older myths to newer frameworks. It also offers a glimpse of Gilgamesh in a domestic role, making music in his city before the plot tips into the uncanny.

The drum, the tree, and the loss

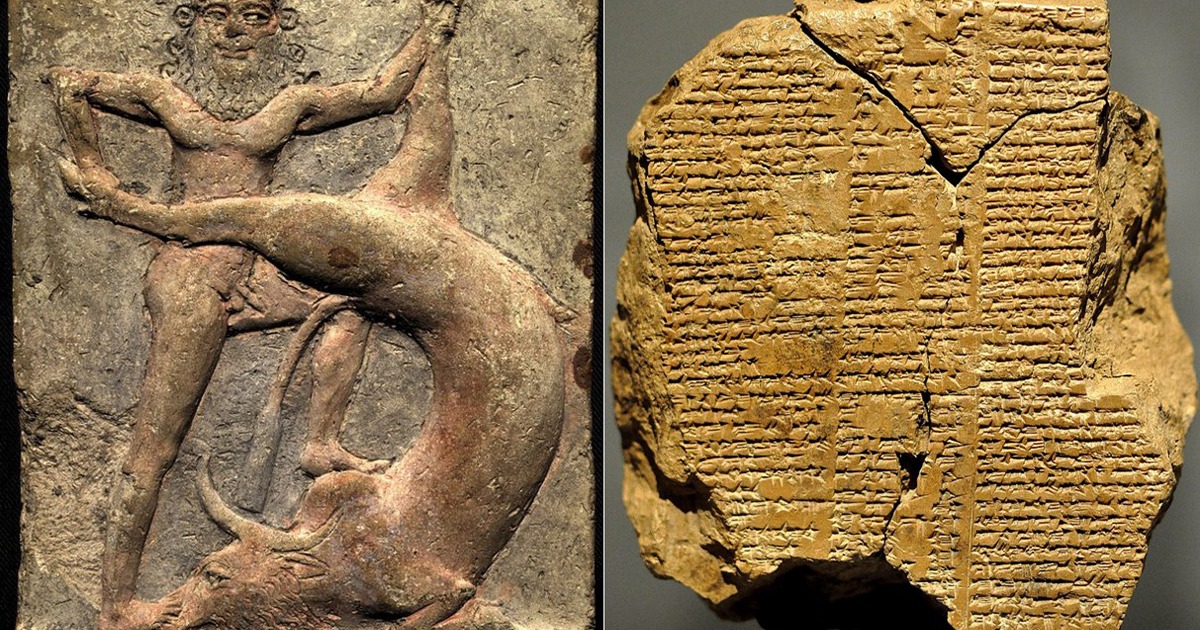

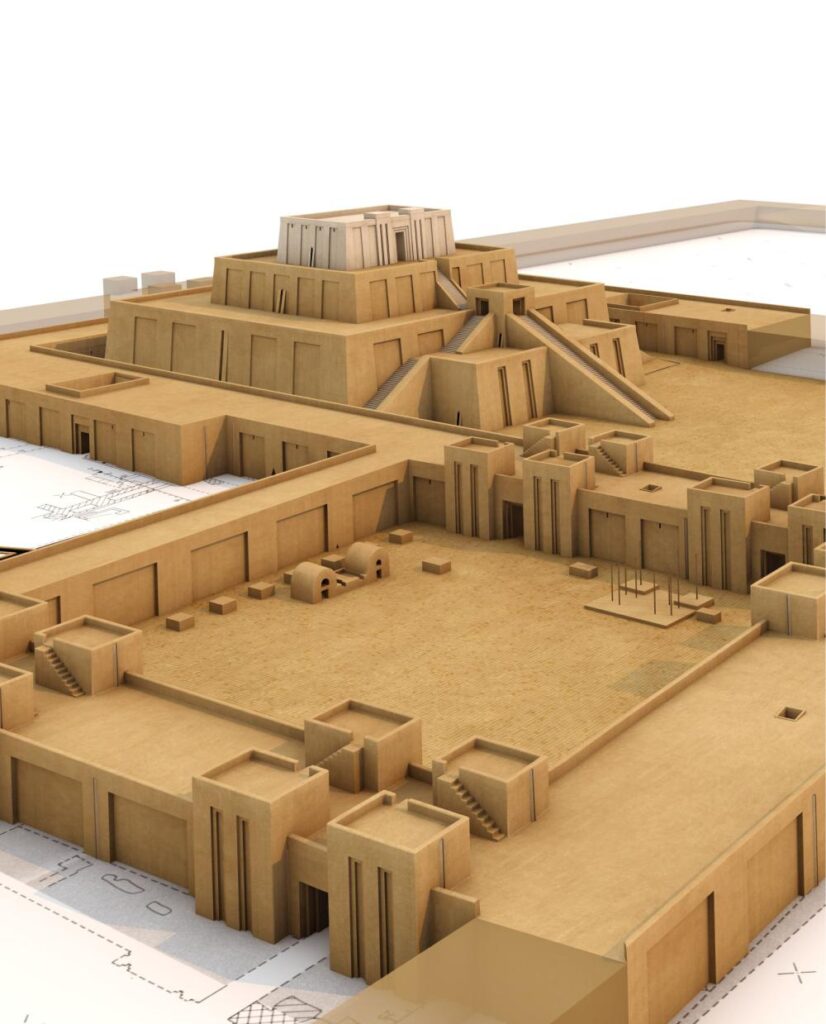

The story begins with a tree planted in Uruk. From its wood, Gilgamesh fashions a drum and its drumstick — instruments that call his warriors and mark the rhythm of the city’s life. But in a turn that seems almost casual, the drum and stick fall through a crack into the netherworld. Their loss is not only practical. In Mesopotamian thought, such items carry a trace of the owner’s essence. To lose them to the realm of the dead is to lose a part of one’s self.

Gilgamesh cannot go after them without breaking the laws that keep the living and the dead apart. So he turns to Enkidu. The friend agrees to descend and retrieve them, but Gilgamesh warns him: obey the underworld’s customs. Do not wear clean clothes. Do not anoint yourself with oil. Do not carry weapons. Do not kiss the loved or strike the hated. Above all, do not make a sound that draws attention.

The rules of the Great Below

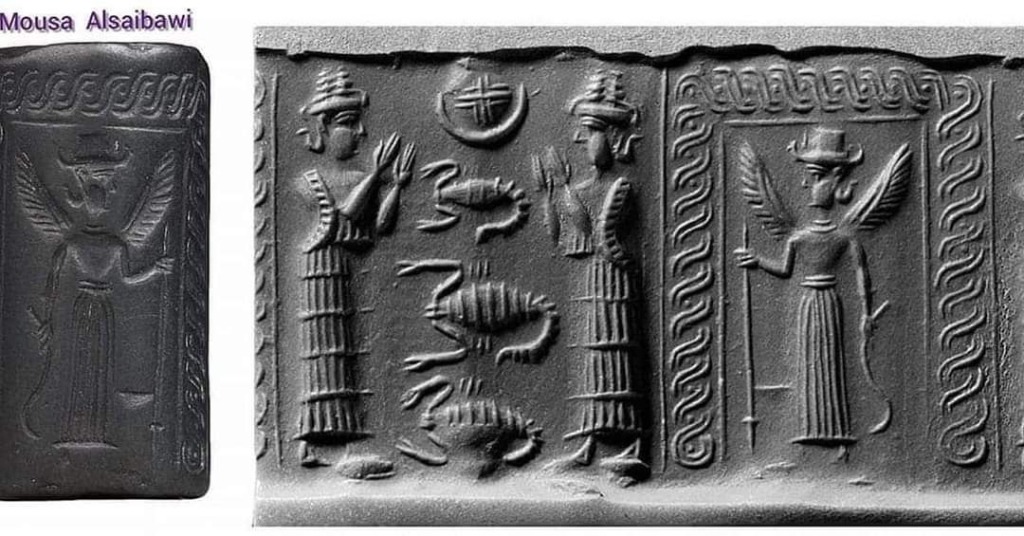

These instructions are not arbitrary. They are part of a consistent pattern in Mesopotamian descent myths. The Great Below is a place of strict etiquette. Clean garments, scented oils, and displays of affection mark one as living, out of place among the dust-eaters. Any breach risks attracting the gaze of the queen, Ereshkigal, or her servants. Once noticed, a living intruder is likely to be kept.

In the story, Enkidu ignores the warnings. He embraces those he loves, strikes those he resents, and uses the fresh clothes and oils of the living. The underworld notices. The gates close behind him. The drum and drumstick are lost to Gilgamesh for good, and Enkidu himself does not return in the flesh.

A voice without a body

Instead, his voice rises through the ground. Gilgamesh hears him and begs for news. What is it like below? How fare the warrior, the child, the man with many sons, the one with none? Enkidu answers each question with a stark image. The man with many sons sits on a cushioned seat, drinking clear water. The one without wanders thirsty. The stillborn child plays with gold, free of care. The warrior fallen in battle is honoured. Those forgotten by the living crouch in darkness, eating scraps dropped through cracks.

These short reports are some of the most vivid underworld portraits in Mesopotamian literature. They compress a whole moral order into a list of fates, graded by family honour, cause of death, and the memory kept by the living. No flames, no pitchforks — just a cool hierarchy of dust.

Why include such a tale?

From a narrative point of view, Tablet XII sits awkwardly after the arc of grief and wisdom that closes Tablet XI. Gilgamesh has already faced death, mourned Enkidu, and learned that immortality is beyond him. Why bring Enkidu back in this ghostly form? One answer is scribal culture. The epic was a living text, taught in schools where students copied older Sumerian compositions alongside the Akkadian masterwork. Including this translated episode honoured the older tradition and expanded the cycle with a moral vignette on underworld customs.

It also reaffirms certain social values. In Mesopotamian cities, proper funerary rites and the upkeep of graves ensured that the dead were remembered — and that their shades lived in some comfort. Neglect could condemn them to thirst and darkness. Tablet XII makes that principle clear in a form no audience could miss.

The underworld as an ordered place

One striking feature of the episode is how normal the underworld seems within its own frame. It is not chaos. It has rules, roles, and rewards scaled to the life one led and the honours one receives. This matches the wider Mesopotamian vision of the cosmos. The Great Above has its councils of gods. The human world has its kings and scribes. The Great Below has its queen, her court, and a bureaucracy that treats the dead as citizens of a final city.

That order is not gentle, but it is predictable. This predictability is what allows heroes to make deals, send messages, and, in some myths, secure rare returns. Enkidu’s failure is not from lack of courage, but from ignoring protocol.

Echoes in other descents

Tablet XII’s rules echo those in Inanna’s descent, Nergal’s visit to Ereshkigal, and later stories from the wider Near East. The shedding of status symbols, the avoidance of living markers, and the strict silence in the queen’s presence form a shared pattern. These echoes help date and connect the stories, showing how themes migrated from Sumerian to Akkadian and beyond.

In the Greek world, similar caution appears in Orpheus’s journey to fetch Eurydice — though there the breach is turning to look back, not wearing clean clothes. The form changes, but the sense remains: crossing the threshold is possible, but only within limits, and those limits are easy to break.

What it tells us about Gilgamesh

The king of Uruk here is not the restless seeker of the main epic. He is a ruler in his city, making music with his people, and relying on his friend for help. The loss of the drum is a local crisis, not a cosmic one. His reaction — asking questions of Enkidu’s shade — shows curiosity about the fates below rather than an attempt to overturn them. In a way, it is Gilgamesh at his most human. He accepts that some losses stand, and turns the moment into a chance to learn.

This human scale may be why the story lingered. It allows listeners to imagine their own questions and answers. What would you ask if you had one conversation with someone returned from the dead?

For the historian and the storyteller

For historians, Tablet XII is a bridge between two eras of literature. It shows Akkadian scribes preserving Sumerian material in translation, adjusting names and details to fit the Gilgamesh cycle. It demonstrates the interplay between myth cycles and the demands of education in Mesopotamian scribal schools.

For storytellers, it is a model of compression. In a few dozen lines, it sets up a domestic scene, stages a descent, establishes rules, enforces them through failure, and delivers a set of vivid vignettes from the land of the dead. It wastes nothing.

Why it still resonates

The images Enkidu gives — the seated man with many sons, the thirsty one with none, the warrior honoured, the forgotten crouched in dark — can slip easily into any time and place. They are not bound to Uruk’s walls or to Sumer’s kings. They speak to how communities remember, reward, and neglect. They speak to the quiet fear of being erased from the living mind.

That resonance is perhaps why Tablet XII survives despite its odd fit. It is a reminder that epic heroes do not always chase the horizon. Sometimes they stand still and listen to a voice from below, taking in the map of a city they will one day enter.

A measured ending

The text closes without recovery of the drum, without rescue for Enkidu, and without a shift in the cosmic order. That in itself is a lesson. Not all stories resolve with triumph. Some serve to mark boundaries, to state plainly: here is where you cannot go, here is what you cannot bring back. For a civilisation that valued law, order, and the balance between realms, such clarity was as valuable as tales of victory.

Tablet XII may never have been meant as the “final chapter” in the modern sense. It may have been a side room in the house of Gilgamesh stories, a place to sit and hear the rules of another world before rejoining the main hall. Yet it holds its own weight, and for those curious about the Mesopotamian underworld, it remains one of the clearest and most memorable guides.