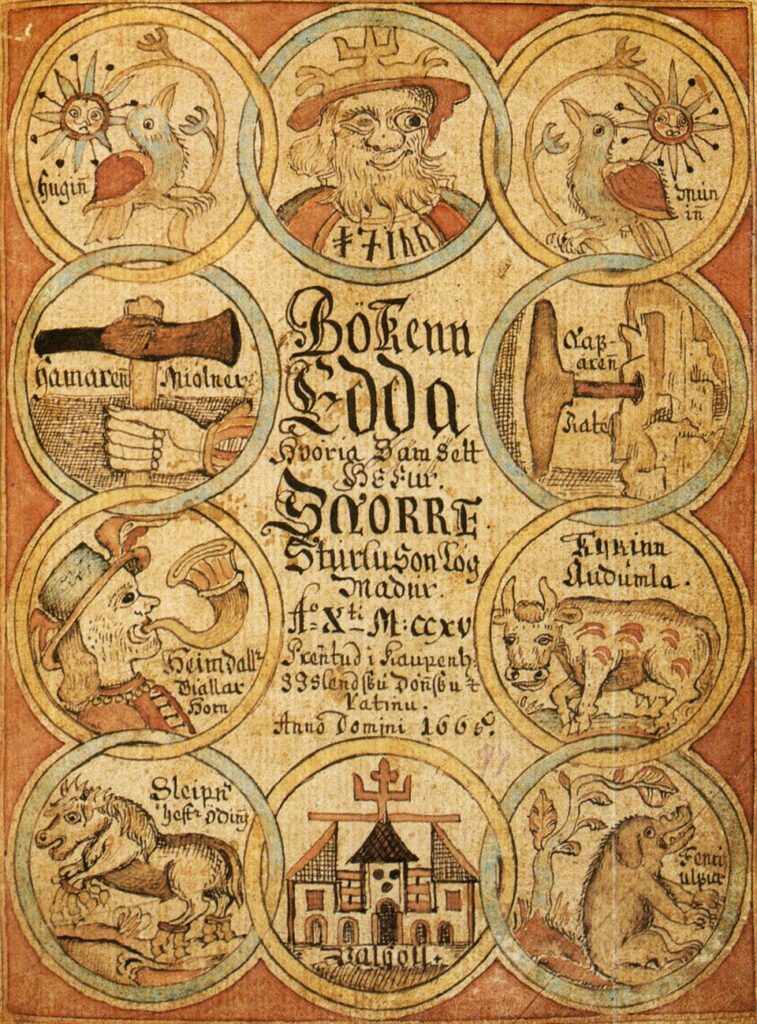

In the long winter nights of the North, stories of gods and giants moved from hall to hall with the mead. Among them, few are told with more satisfaction than the tale of Útgarða-Loki and the day he made Thor look like a fool. It is part of the Prose Edda, written down by Snorri Sturluson in the 13th century, but the tricks it records feel older. The story blends travel, tests of strength, and the sly humour of a host who lets his guests set their own traps. By the end, Thor has swung his hammer in vain, Loki has raced himself breathless, and both have to admit they were beaten from the start.

Útgarða-Loki’s name ties him to Útgarðr, the ‘Outer Enclosure’ beyond the gods’ realm. This is the land of the jötnar, giants who rival the gods in strength and cunning. In the story, he appears not as a roaring brute, but as a courteous, unsettling king who hides his tricks in plain sight. That choice matters. A giant who wins by force is one thing; a giant who wins by wit leaves a sharper sting.

The road to Útgarðr

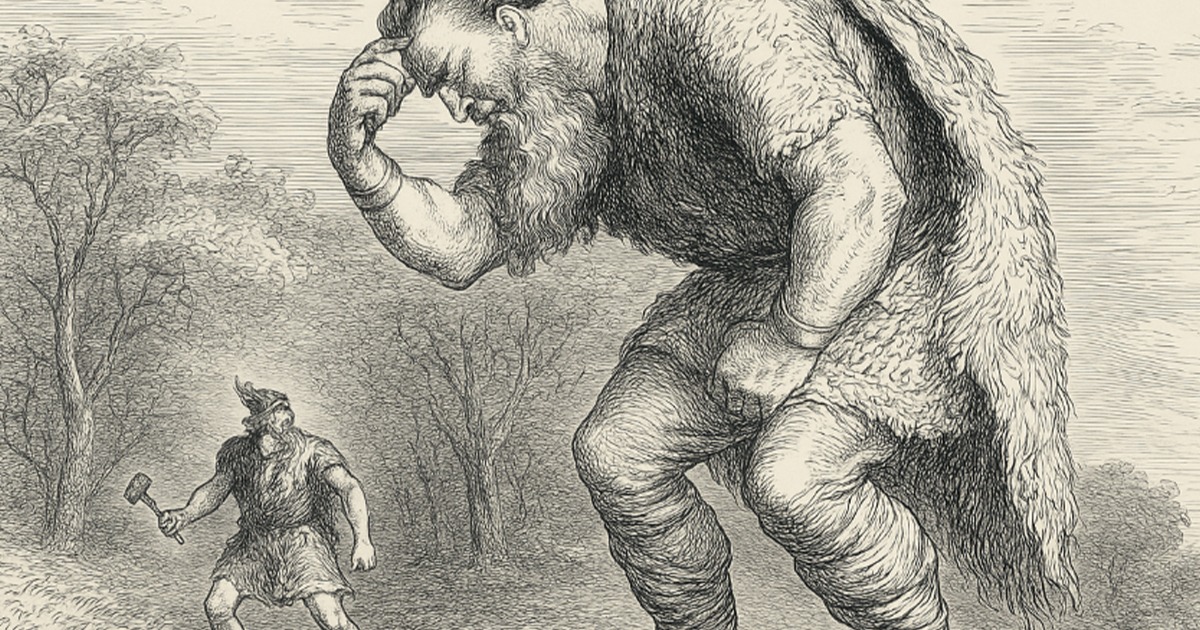

The episode begins with Thor, Loki, and two human servants, Þjálfi and Röskva, travelling toward the land of the giants. They spend the night in a strange hall that turns out to be the thumb of a sleeping giant named Skrýmir. In the morning, Skrýmir offers to carry their provisions in his great bag. At night, Thor tries three times to smash Skrýmir’s head with Mjöllnir while the giant sleeps. Each blow feels true, yet Skrýmir wakes only to ask if a leaf or acorn has fallen on him. The bag, tied in knots Thor cannot untangle, stays shut. The journey goes on.

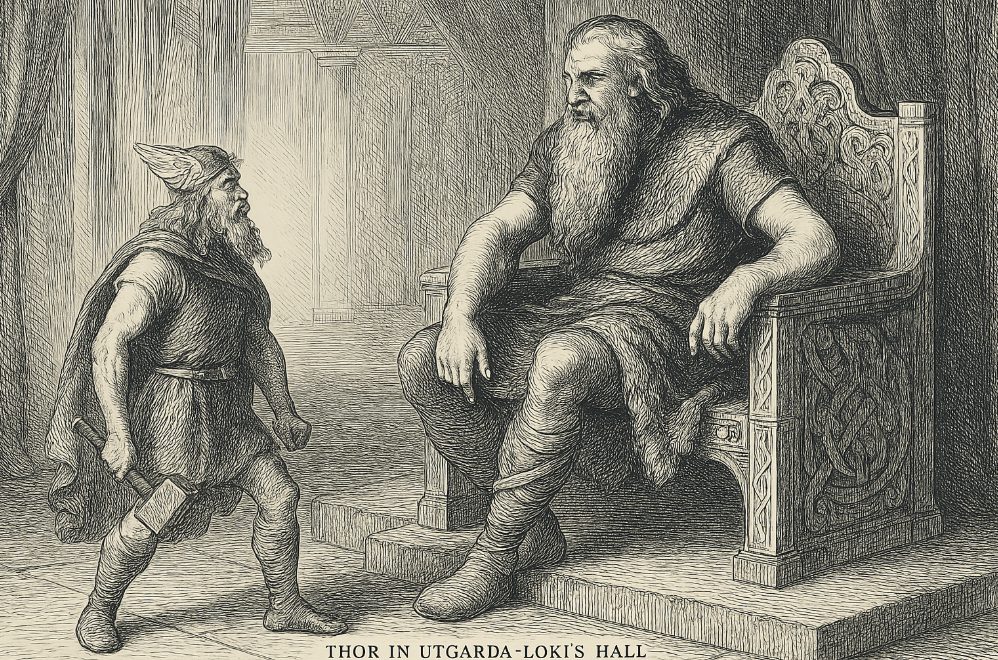

By the time they reach Útgarðr, Thor is short on patience. The hall they enter is vast, the benches long, and the king who greets them—Útgarða-Loki—welcomes them with a cool politeness. No one here is impressed by gods from Asgard. Instead, the king proposes contests, each tailored to the visitor’s supposed skill. The stakes are pride, and the rules sound simple. Thor and Loki agree.

Loki’s eating match

Loki’s trial comes first. He boasts of his ability to eat fast, and Útgarða-Loki sets him against a man named Logi. A trough of meat is placed between them. They start at opposite ends, chewing quickly toward the middle. Loki finishes the meat on his side just as Logi finishes his—but Logi has eaten meat, bone, and even the wooden trough. Loki must admit defeat. The company nods, amused. The host calls for the next contest.

Þjálfi’s race

Thor’s servant Þjálfi is famed for his speed. He is set to race a youth named Hugi. At the first mark, Hugi finishes far ahead. In the second race, Þjálfi is closer but still loses. In the third, he strains every muscle and yet Hugi reaches the goal while Þjálfi is barely halfway. The hall murmurs approval at the skill on display, and the giant king smiles.

Thor’s drinking horn

Finally, Thor faces his first challenge: to empty a drinking horn. He takes three long draughts. The horn still seems nearly full. Thor hands it back, breathing hard. His pride stings. The host nods thoughtfully, as if surprised. Then comes the second trial: lift the king’s cat. Thor seizes it by the belly, straining to raise it from the floor. The cat arches its back until only one paw leaves the ground. Laughter stirs around the hall.

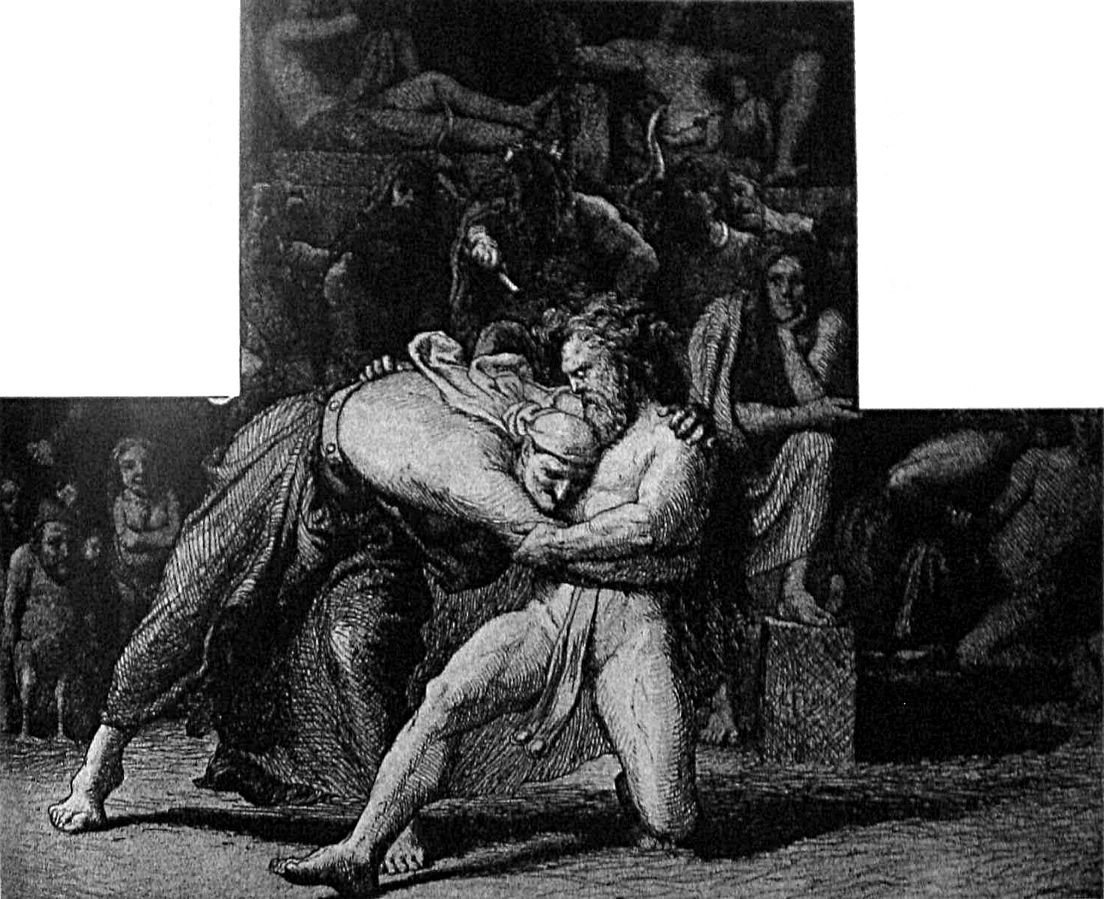

Thor’s wrestling match

The last contest is a wrestling match against an old woman named Elli. Thor grips her firmly. She stands her ground. Slowly, she forces him down onto one knee. The crowd claps. The challenges end. Útgarða-Loki declares the guests have done well ‘for their kind’ and offers them a night’s rest. In the morning, he walks with them beyond the walls.

The reveal

Once outside, Útgarða-Loki drops the mask. He is not merely a host but the very Skrýmir they met on the road. The bag Thor could not untie was bound by magic. Thor’s three hammer blows? Each one would have killed him, so he moved a mountain into the way. The dented peak still stands.

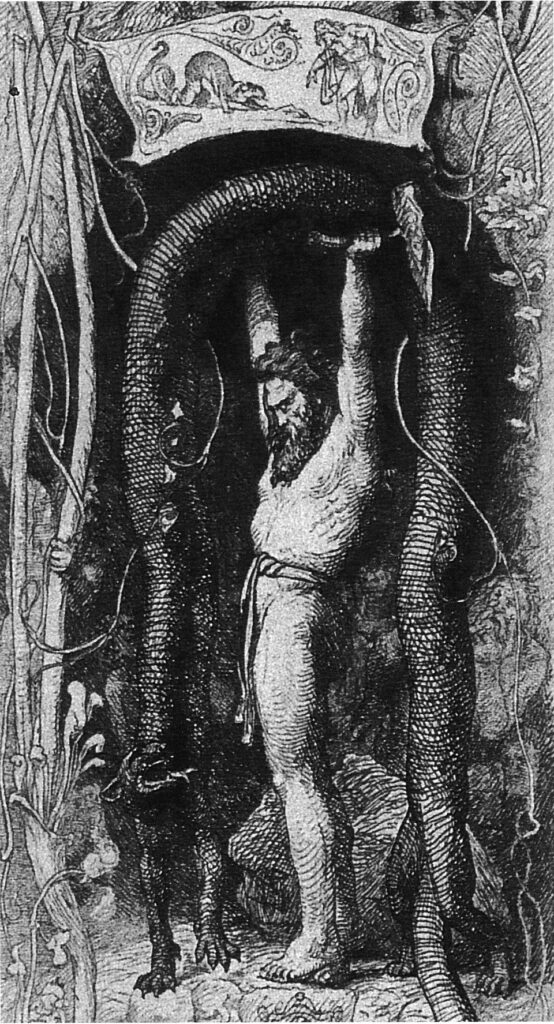

As for the contests: Loki’s opponent, Logi, was wildfire itself—no flesh could outrun it. Þjálfi raced Hugi, whose name means ‘thought’. Nothing moves faster than that. Thor’s horn drew from the sea; his deep draughts caused the tides. The cat was the Midgard Serpent, Jörmungandr, who encircles the world; lifting even a paw was a feat. The old woman was Elli, old age, who eventually defeats everyone. Thor clenches his fist, ready to strike, but Útgarða-Loki vanishes. The hall, the walls, the king—gone. The travellers stand in an empty plain.

What the story says about Thor

This is one of the few myths where Thor loses. Even then, the defeats come from deception, not lack of strength. The point is not to humiliate the god but to show the limits of raw power. Útgarða-Loki wins by reframing the rules so that every contest is unwinnable. The lesson is double-edged: strength alone can be turned aside, and cunning can make the mighty look small.

In Norse culture, which prized both courage and craft, such tales balanced the image of a thunder-god who smashes giants. Here, the giant out-thinks him. It is a reminder that wisdom comes in many forms—and that the gods themselves face limits.

Útgarða-Loki’s role among the giants

The jötnar are not all the same. Some are forces of chaos; others keep their own kind of order. Útgarða-Loki belongs to the latter. He keeps his hall, sets rules, and treats guests with formal courtesy. Yet he bends those rules to his advantage. His power is not in the axe but in the mind. Against a god famed for action, he stages a theatre of impossibility.

In the cosmology of the Norse, this makes him a mirror to Odin, who also wins through wit—though Odin’s deceptions tend to favour his own side. Útgarða-Loki plays for himself and his realm, which lies beyond Asgard’s reach. The meeting between him and Thor is less a battle than a cultural exchange with teeth.

Why the tricks work

Each challenge is built on a transformation. The contestants face something other than what they think. Loki sees a man; he eats against fire. Þjálfi sees a runner; he races against thought. Thor sees a horn; he drinks the ocean. He sees a cat; he grapples with the serpent that circles Midgard. He sees an old woman; he wrestles old age itself. The metaphor is not subtle, but the way it is revealed makes it sting. These are contests no one can win, because they are set against the fabric of the world.

The humour of the reveal

The ending turns the whole adventure on its head. The grandeur of the hall, the polite hosting, the easy confidence—it all vanishes like a mirage. The audience gets the satisfaction of seeing the proud brought low, but also of realising that they have been in on the joke from the start. Storytellers could stretch the reveal for effect, letting listeners guess what each opponent really was before confirming it.

Connections to other myths

Trickster figures recur in Norse myth, but Útgarða-Loki is distinct from Loki the god. Despite the name, the two are separate characters in most scholarly readings. Their shared traits—wit, misdirection, the pleasure of the reveal—mark them as belonging to the same cultural type. Giants as a whole are often opponents, but here the contest is more sport than war.

The episode also resonates with folktale motifs found far beyond Scandinavia: the unwinnable contest, the disguised opponent, the final unmasking. These themes travel well because they speak to a universal truth: appearances mislead, and pride is easily caught in a snare.

What it meant to its first audiences

In a hall on a cold night, this story works as comedy, caution, and commentary. The comedy is obvious—Thor, the great hammer-wielder, losing to an old woman. The caution lies in the reminder to measure opponents carefully. The commentary touches on the Norse view of fate: some limits cannot be broken, no matter the will or weapon.

It also reinforces social values. Hospitality here is a weapon; courtesy masks hostility. Listeners would understand the need to read between the lines, to test the truth of what is offered. In a world of shifting alliances and long winters, such lessons kept company with the ale.

Legacy in later retellings

The Útgarða-Loki episode survives because it is adaptable. It appears in children’s books as a set of funny contests. It is retold in modern novels as a clash of archetypes. Illustrators love its mix of domestic absurdity—a cat that will not be lifted—and cosmic stakes. The Midgard Serpent, the ocean drained into a horn, and the personification of old age all offer striking visuals.

In popular culture, the tale often blurs into the larger figure of Loki, creating a single composite trickster. Scholars keep the distinction, but storytellers work with what audiences know. The heart of the story—Thor bested by wit—remains intact.

Why it still works

Modern readers and listeners still enjoy seeing the strong outmanoeuvred. The challenges remain relatable: eating, running, drinking, lifting, wrestling. Only at the end do we learn that each was impossible. The humour and the sting are the same as they were in a longhouse centuries ago.

At its core, the story says: even the mighty have blind spots, and cleverness can turn those blind spots into walls. It is a truth as old as the sagas, and as current as any game of strategy today.