Presentism in Ancient History is the habit of reading ancient evidence through contemporary assumptions, values, and language. It is easy to commit and hard to detect. This guide clarifies what presentism is, why it skews arguments, and how to build methods that respect context while still asking modern questions responsibly.

Ancient history is not a mirror; it is a different country with unfamiliar institutions, words, and mental worlds. We can learn from it only if we notice where our own categories warp what we see. Below you will find a clear definition, core mechanisms of distortion, case studies, a step-by-step method to reduce bias, and practical tips for citations, translation, and images.

Defining presentism (without retreating into relativism)

Presentism is not the same as relevance. We can ask present-day questions about power, economy, gender, law, or race. The mistake lies in importing modern definitions wholesale and then grading ancient cultures against them. When we impose today’s morality tests, legal standards, or social categories onto the ancient record, we misread both what the sources meant and what audiences heard.

Two quick rules keep the boundary clear. First, interpret sources according to ancient contexts; second, apply insights responsibly to modern debates after that work is done. In other words, read as a historian before you read as a citizen.

Where presentism sneaks in: seven common mechanisms

1) Translation drift

Loaded words in English (freedom, democracy, religion, race) rarely map cleanly onto Greek, Latin, Egyptian, or Akkadian terms. Translating dēmokratia as “democracy” invites readers to imagine universal suffrage, secret ballots, and liberal rights. None of that applies to classical Athens. The fix: annotate key terms and, when possible, quote or transliterate the original word with a brief gloss.

2) Moral anachronism

Judging ancient actors by modern ethical frameworks can yield satisfying verdicts but poor history. We should not excuse harm, yet we must place choices within ancient horizons of possibility: laws, customs, available arguments, and costs. Good writing separates two sentences: “By modern standards this was unjust” and “Within their world this action signalled X.”

3) Category confusion

Modern binaries (public/private, sacred/secular, state/market) often blur in antiquity. City, cult, family, and economy braided together. If you keep forcing clean modern boxes, evidence will look inconsistent when it is actually integrated by design.

4) Teleology

Reading outcomes backward (“Rome was bound to conquer,” “Athenian democracy evolved inevitably toward us”) makes contingency disappear. Teleology turns history into a conveyor belt and hides roads not taken. Replace inevitability with pathways, forks, and lost alternatives.

5) Source selection bias

Our archive is skewed: elite authors, court art, durable materials, lucky survivals. If we keep citing the same narrow genre (e.g., historiography) without epigraphy, papyri, archaeology, or comparative material, we amplify the bias already in the record.

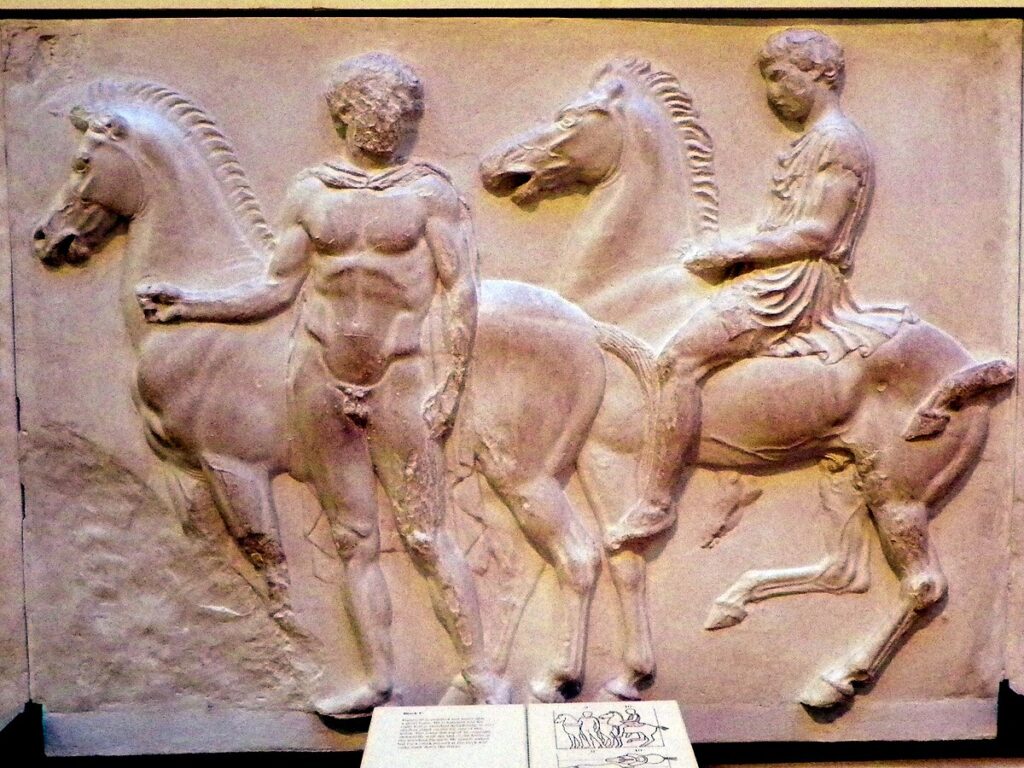

6) Museum mediation

Labels, lighting, and famous objects can overdetermine meaning. A single inscription under bright glass can look like the voice of a people. Use museum displays as starting points, then check full object records, find-spots, and parallel exemplars.

7) Present-day politics and headlines

Modern debates (citizenship, empire, repatriation, ethnicity) offer helpful questions but also built-in heat. Frame links explicitly: “We ask this modern question after we reconstruct ancient meanings.” The order matters.

Case studies: how modern bias distorts the past

Interpreting “democracy” at Athens

Calling classical Athens a “democracy” invites readers to imagine modern citizenship. But Athenian dēmokratia excluded women, most migrants, and enslaved people; it used sortition, public pay for jury service, intense face-to-face speech, and ritual closure. Presentism enters when we grade Athens against 21st-century norms rather than reconstructing the distinctive mechanics and aims of the Athenian system.

Reading imperial ideology in Roman sources

Descriptions of “civilising missions” or “bringing peace” sound familiar. If we project recent imperial rhetoric onto Augustan monuments or Tacitean prose, we may miss how Roman audiences linked conquest with cosmic order, ancestral exempla, and patronage networks. The remedy is to read claims alongside provincial epigraphy, military diplomas, and archaeology rather than assuming modern frames of empire.

Gender in myth and law

Presentist readings often flatten women’s roles into modern boxes (victim/hero). Ancient evidence shows authority expressed through ritual, property, priesthoods, or guardianship frameworks we lack. Instead of importing modern categories, track the levers that produced power in each context.

Slavery, race, and language

We should state plainly that forced labour and enslavement in antiquity caused profound harm. The presentist trap is to equate ancient terms and social boundaries directly with modern racial constructs. Ancient languages mark status, origin, and ethnicity differently and inconsistently. Careful philology and onomastics help prevent category mistakes.

The “great man” lens

Modern leadership literature often pulls Alexander, Caesar, or Pericles into a universal “CEO” frame. That frame strips away gods, ritual, civic festivals, land settlements, and law that did as much work as any single person. Replace “leadership secrets” with systems thinking: institutions, incentives, and symbolic capital.

How to reduce presentism: a practical method

1) Rebuild context before comparison

For any claim, specify time, place, genre, and audience. Identify the medium (clay, papyrus, stone, bronze, wall painting). Ask who paid for it, who saw it, and how it circulated. Note which groups the evidence omits or marginalises.

2) Annotate key terms and keep a glossary

When a word carries cultural load—dēmokratia, euergetēs, nomos, maat, šarru—define it, cite examples, and prefer transliteration to overconfident equivalents. If you must translate, footnote the compromise.

3) Triangulate genres

Pair narrative sources with epigraphy and archaeology. Set Herodotus or Livy beside decrees, dedications, coin legends, and site reports. Closed loops of literary quotation amplify one elite voice; triangulation tests claims against lived textures.

4) Separate description from evaluation

Write what a practice was and did within its world, then bracket a distinct paragraph for present-day ethical evaluation. Readers can hold both truths when you keep them formally separate.

5) Expose your inference chain

Show how you move from fragment to claim: transcription → translation → parallel texts → material context → inference. If a step is contestable, label it. Presentism thrives in hidden leaps.

6) Use images like evidence, not decoration

Caption objects with date, place, material, and function. Explain what a viewer then would have noticed. Link to object records, not just viral images. Good captions are mini-arguments.

7) Track your own vantage point

Note your disciplinary training, language limits, and modern stakes. Reflexive writing is not indulgence; it is method. When your background increases risk (e.g., strong opinions about modern empire while reading Roman sources), add counter-voices in citations.

Working examples: doing the history first

Law and “rights”

We are tempted to ask whether ancient people had “rights.” That word carries modern legal theory. A safer historical move is to map claims, protections, and procedures available to groups and to watch who could speak in which venue. Then, in a second step, compare those maps with modern rights talk.

Religion and “belief”

Ancient cult emphasised practice over private belief: sacrifices, festivals, processions, oaths. If we import a modern “religion as inner conviction” model, we’ll misread dedicatory inscriptions and overlook how ritual created civic time.

Economy and “markets”

Prices, coinage, and trade existed, but embedded within kinship, patronage, temple estates, and conquest. Projecting modern deregulated markets back onto the ancient Mediterranean hides coercion, redistribution, and ritual economy.

Race, ethnicity, and identity

Ancient texts mark difference via language, custom, dress, homeland, and law. The temptation is to paste modern racial categories on top. Better: show how names and statuses worked locally; then discuss how later readers racialised those categories in reception history.

How museums and headlines shape readings

Public debates—from the Parthenon sculptures to the display of imperial trophies—create pressure to draft antiquity into modern arguments. Use the pressure as an opportunity to teach method. Put object labels beside source extracts and ask: whose voice; which audience; what message did this send then.

Checklist for writers, teachers, and students

- Focus keyword anchor: “Presentism in Ancient History” appears in your title, intro, and subheadings—keep it visible as a concept, not a buzzword.

- Gloss key terms: give the ancient word, a short gloss, and an example.

- Triangulate: literary source + inscription/papyrus + archaeology.

- Caption like a scholar: date, place, medium, function, audience.

- Separate description from evaluation: two paragraphs, two lenses.

- Expose inference chains: let readers see steps and doubts.

- Own your standpoint: say what you bring and where you’re blind.

Further reading and object gateways

To anchor arguments in primary material, consult the British Museum Collection Online and The Met Open Access. For law and kingship, pair the Hammurabi stele with cuneiform court records and contracts; for multilingual power, set the Behistun Inscription beside local Elamite and Akkadian versions. When you cite, give inventory numbers or object IDs when available.

FAQ

Does avoiding presentism mean refusing moral judgement?

No. It means reconstructing ancient meanings first, then making moral evaluations explicitly and fairly. You can do both; doing them in order improves both.

Is all comparison presentist?

Comparison becomes presentist when it imposes modern categories before doing historical work. It becomes historical when it lets ancient terms lead and then frames differences carefully.

Can we write for public audiences without presentism?

Yes. Use active verbs, clear structure, and vivid objects. Explain your method in plain language. Readers accept complexity when you show why it matters.

How does this affect classroom practice?

Design assignments that force triangulation (text + inscription + object). Require students to gloss key terms and to mark where they step from description into evaluation. Presentism shrinks when method becomes visible.