Hathor’s name calls to mind music, perfume, dance, and the slow sway of palm fronds in the Nile breeze. She is the “Mistress of Joy,” the patron of love, and the welcome face who greets the dead with an embrace. Yet in one of Egypt’s most vivid myths, she is also the hand of divine wrath — a goddess who walks the earth in fury so great that the survival of humanity hangs on a trick of deception. This side of her character, rarely shown in popular depictions, is a reminder that Egyptian deities did not live in neat moral boxes. Hathor could heal and destroy with equal force.

The tale survives in the New Kingdom text often called the “Book of the Heavenly Cow.” It frames her rage as part of a cosmic drama: the sun god Ra grows weary of human insolence and sends his eye to punish them. In this role, Hathor takes on the fearsome form of Sekhmet, a lioness whose breath burns and whose claws leave no survivors. What follows is a story of vengeance, blood, and a last-minute turn towards mercy — though even that mercy comes drenched in red.

The setting: rebellion under Ra’s eye

In the beginning of this episode, Ra rules both gods and people. His light covers the world, his voice directs the divine council, and his orders keep the balance of maat — the principle of cosmic truth and order. Over time, however, the humans grow restless. They speak against him. Some accounts suggest they plot to overthrow his rule. Ra, affronted and wary, calls a secret council of elder gods. The verdict is harsh: rebellion must be answered, not ignored.

To carry out the sentence, Ra sends his eye — a divine aspect that can appear as different goddesses — down to earth. This “Eye of Ra” is not a passive observer. It is the focused, personal wrath of the sun, given flesh and motion. In this telling, the eye becomes Hathor. Her gentle smile fades; in her place rises a huntress with a lion’s face and the patience of a predator.

From Hathor to Sekhmet

Transformation is a hallmark of Egyptian myth. The same goddess could hold multiple aspects, shifting with context and need. As the Eye of Ra touches the ground, Hathor’s sweetness hardens into Sekhmet’s ferocity. She walks through the rebels like a firestorm. The texts relish the detail: blood runs like the Nile in flood, bodies lie in heaps, and the smell of slaughter carries on the wind. Sekhmet does not pause to consider guilt or innocence. The rebellion called for punishment; she delivers it without limit.

This is the point in the story where the danger shifts. The punishment has gone beyond a targeted act. The slaughter has become an appetite. Sekhmet is no longer merely avenging Ra; she is hunting for the sake of the kill. The gods above watch with growing alarm. If nothing changes, there will be no humans left to uphold the temples or honour the divine.

Ra’s dilemma and the plan of the gods

Egyptian myth often balances ferocity with cunning. Confronting Sekhmet by force would only feed the destruction. The solution must turn her nature against itself. Ra commands that a great quantity of beer be brewed — enough to fill jars beyond counting. To this, the brewers add red ochre, staining the liquid to match the colour of fresh blood. At dawn, they pour the crimson flood over the fields where Sekhmet will walk.

When she arrives, the lioness sees only what her sharpened senses expect: more blood, more prey. She drinks. The taste is strange, but the colour convinces her. She drinks deeply, and the beer’s weight begins to cloud her focus. By the time the jars are empty, the goddess sways. Her rage cools into drowsy laughter. In this softened state, she becomes Hathor again — the festival goddess, the bringer of music, her thirst now turned to joy.

The aftermath: mercy with conditions

Humanity survives, but not without a scar in the divine record. The Book of the Heavenly Cow suggests that Ra withdraws from direct rule after this event. He ascends to the sky on the back of the heavenly cow, leaving the daily care of the world to other gods. Hathor remains among them, but the memory of her transformation into Sekhmet lingers. It becomes a warning woven into festivals, rituals, and the iconography of temples.

In later cult practice, Sekhmet’s temples receive offerings intended to keep her calm. Priests pour beer coloured red during certain rites, re-enacting the moment when destruction was stayed. Hathor’s shrines, meanwhile, celebrate her role as the joyous goddess, but always in the knowledge that joy and wrath live in the same divine being.

The Eye of Ra: a role shared across goddesses

The title “Eye of Ra” does not belong to Hathor alone. In different myths, it can fall to Tefnut, Mut, or other lion-headed deities. What they share is the role of enforcer. The Eye is the sun god’s arm in the world, able to protect or punish. This fluidity shows how Egyptian theology allowed identities to blend without contradiction. Hathor could be the gentle lady of turquoise, the protector of miners in Sinai, and still bear the same destructive potential as Sekhmet when the balance of maat required it.

This also helps explain how the myth carried weight in political life. Pharaohs claimed to act as the upholder of maat, yet they also needed to be feared. The image of a ruler able to summon the Eye of Ra sent a clear message: kindness and terror walk in step, and either could visit depending on loyalty.

Festivals of beer and renewal

The episode of the blood-coloured beer found ritual echoes in the “Festival of Drunkenness.” Celebrated in honour of Hathor, it encouraged participants to drink, dance, and play music deep into the night. While it sounds purely festive, the origin is deadly serious. The beer recalls the moment of salvation, when destruction turned to celebration. The excess, carefully contained within the bounds of the festival, acted as a controlled vent for the forces Hathor embodied.

Archaeological finds at temple sites include vats, drinking vessels, and inscriptions linking the festival to renewal. Participants woke the next day with more than a hangover; they stepped into the new year cleansed of the old cycle’s dangers, much as humanity in the myth had survived a brush with extinction.

Lessons from the bloodthirsty side

To modern eyes, the idea of a goddess shifting from nurturer to destroyer in a breath can feel jarring. In the Egyptian view, it was the nature of divine power. The Nile that feeds can also flood. The sun that warms can scorch. Hathor’s duality embodies this truth. Joy and wrath are not opposites to be reconciled; they are parts of a whole, each necessary to maintain balance.

The story also underlines the importance of cleverness in Egyptian thought. Force is met with force only as a last resort. More often, wit and ritual shape the outcome. The red beer is a masterstroke: it feeds the destructive instinct just enough to divert it. In doing so, it redefines victory not as the destruction of the opponent, but as the restoration of harmony.

From myth to daily life

For ancient Egyptians, Hathor’s wrath was not a remote danger. Drought, plague, and political unrest could all be read as signs of the Eye’s displeasure. Farmers, craftsmen, and traders knew the value of offerings, music, and public rites that kept the goddess smiling. On the personal level, amulets bearing her face promised protection in love and childbirth, while also invoking her role as a defender against chaos.

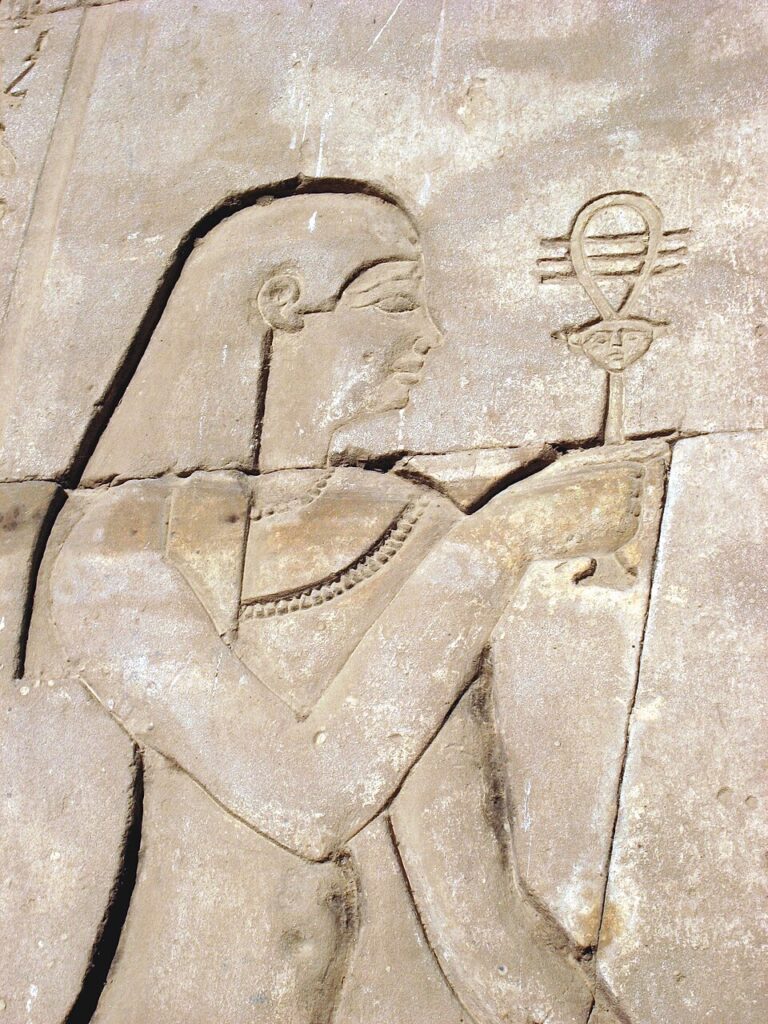

In art, she appears with the horns and solar disk, sometimes flanked by symbols of music. Yet in temple inscriptions, the shadow of Sekhmet is never far. Even the most delicate carving of Hathor’s face carries the authority of one who once waded through rebellion’s blood and stopped only when she chose.

Why the myth endures

Hathor’s near-destruction of humanity remains one of the most striking pieces of Egyptian literature. It offers drama, tension, and a resolution that hinges on understanding the nature of the one who must be stopped. It also speaks to universal concerns: how to temper anger, how to preserve what is valuable without losing strength, and how to recognise when enough has been done.

Modern retellings often soften or skip the violent heart of the story, focusing instead on Hathor’s role in music and love. Yet the bloodthirsty side gives her depth. It reminds us that even the most life-affirming powers can turn dangerous if unchecked, and that wisdom lies in knowing how to guide them back to balance.