Athens Before It Called Itself Free

In the seventh century BCE Attica was a patchwork of aristocratic estates. Land determined status, and one bad harvest could doom a peasant to debt‑bondage. Anger simmered. In 594 BCE the reformer Solon abolished the enslavement of citizens for debt, recalled exiles, standardised weights and measures, and allowed smallholders to sue powerful landlords. His laws bought breathing space, yet the great clans still monopolised high office and stifled broader participation.

The deadlock broke—paradoxically—under a tyrant. Peisistratus, an ambitious noble, staged an assault on himself, secured a bodyguard, and built it into a private army. His one‑man rule, and the shorter reign of his sons, weakened the very aristocracy that had blocked reform. When the dynasty collapsed, ordinary Athenians had learnt that government could function without an inherited elite.

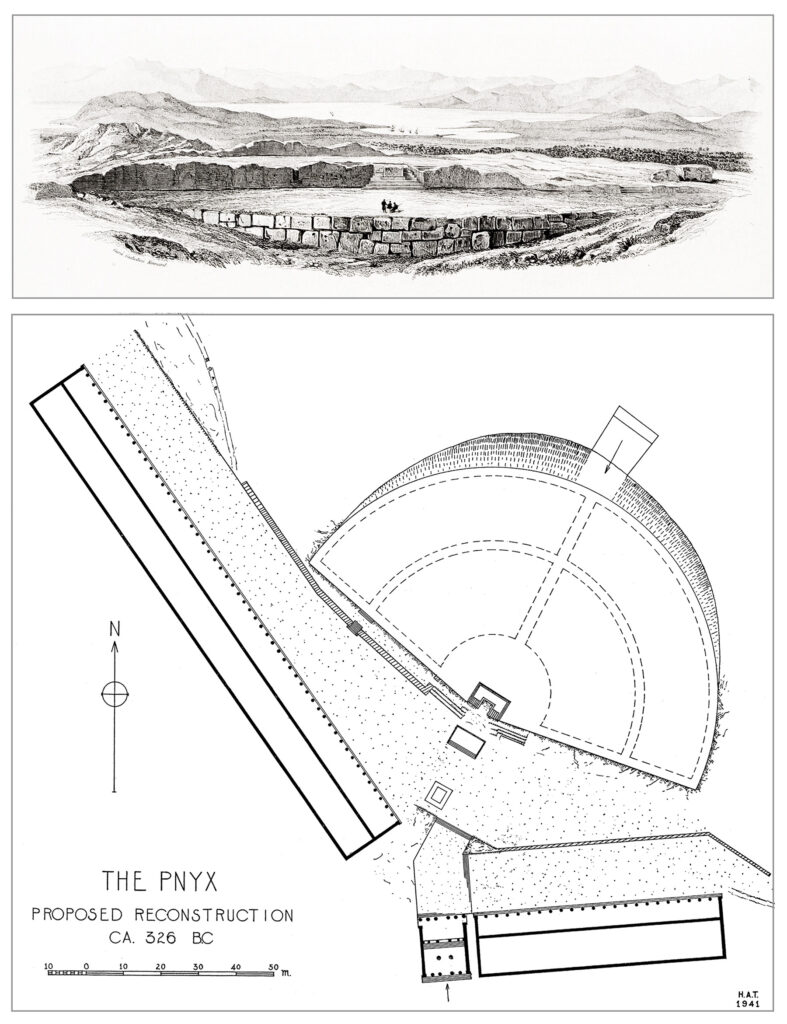

A New Order on the Pnyx

Cleisthenes seized the opening in 508 BCE. He divided the countryside into demes, grouped them into ten tribes that mixed coast, plain, and hill, and grounded citizenship in local registration rather than pedigree. The redesign empowered the ekklesia—all male citizens over eighteen—as the engine of law. Six thousand had to gather on the rocky hill called the Pnyx for major decisions, a demanding quorum that was nonetheless reachable in a city teeming with sailors, shepherds, and potters eager to speak.

Attendance defined adulthood. Heralds swept the agora trailing a crimson‑stained rope; any man caught with dye on his cloak but absent from the meeting paid a fine. The franchise remained narrow—women, enslaved people, and resident foreigners (metics) stayed outside the political tent—yet Athens had stumbled upon a radical idea: authority could circulate among ordinary households instead of resting on bloodlines.

Radical Experiments: Pay for Service and Selection by Lot

Pericles, dominant from the 460s BCE, persuaded citizens to pay jurors two obols a day—later three—so that civic duty did not starve a farmer. He also enlarged sortition, the drawing of lots, for most offices. Election persisted for posts demanding proven skill, such as generals and treasurers, but everyday administration became a civic draft. To critics it sounded reckless; to supporters it embodied trust in the average Athenian’s sense of honour.

Power was not merely shared; it was kept moving. The presidency of the Council of Five Hundred rotated daily, meaning any olive‑grower could wake as head of state and return to pruning trees the next dawn. No ancient society spread authority so thin, and few modern ones have dared to match it.

Golden Age, Hidden Fault‑Lines

The half‑century after the Persian Wars dazzles through marble and verse. The Parthenon crowned the Acropolis, Sophocles probed pride on stage, and Herodotus invented narrative history. Glory, however, carried a bill.

Imperial tribute. Allies in the Delian League paid into a collective fund—moved from Delos to Athens in 454 BCE—nominally for defence but increasingly for temples and festivals. Island poleis grumbled that they were bankrolling Athenian vanity projects.

Social inequality. Naval wages lifted the urban poor, yet land remained unevenly divided. Families who drew both rent from estates and pay from public service prospered while labourers queued for subsidised grain. Comic poets, especially Aristophanes, mocked assemblies where voters chased stipends instead of arguments.

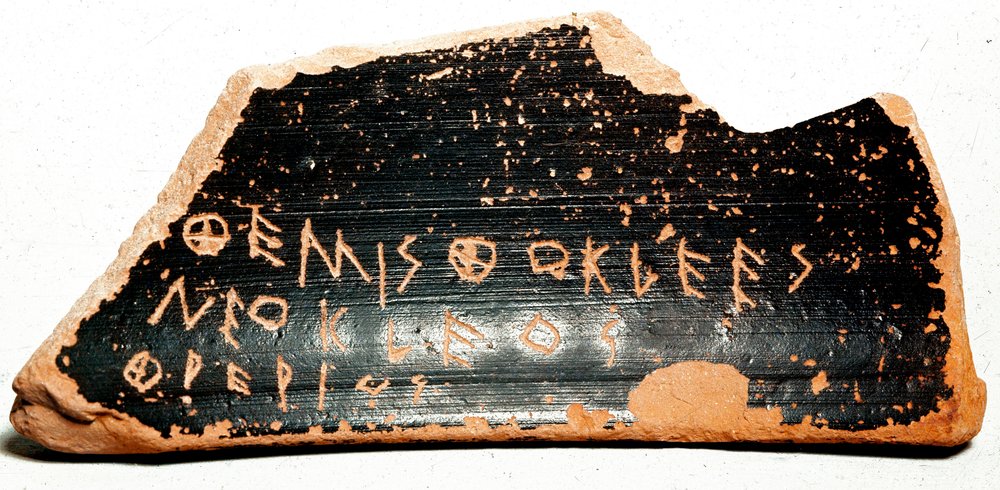

The annual custom of ostracism—exiling one citizen for ten years—was meant as a safety valve against dictatorship. In practice it sometimes banished the very commanders the city later needed in war.

War Puts Democracy on Trial

When Sparta declared war in 431 BCE, Pericles advised a defensive posture: shelter behind the Long Walls, avoid land battles, and harry the enemy at sea. The plan faltered when plague swept the overcrowded city, killing perhaps a quarter of its people—including Pericles himself. Leadership devolved to a carousel of orators whose brilliance outpaced their judgment.

The assembly’s most ruinous wager was the Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BCE). Seduced by visions of quick victory and Sicilian silver, voters sent more than two hundred ships to capture Syracuse. The armada was annihilated; survivors died in stone quarries. Panic triggered an oligarchic coup in 411 BCE, installing a Council of Four Hundred. The experiment imploded within months, but the precedent lingered. After Sparta imposed surrender in 404 BCE, a harsher junta—the Thirty Tyrants—ruled with executions and property seizures until a citizen army restored democracy in 403 BCE, bruised and wary.

Why It Fell Apart

External shock. Twenty‑seven years of attritional war drained the treasury and corroded the patience needed for deliberation.

Inequality and patronage. Stipends meant to broaden inclusion turned into factional currency while property gaps widened.

Institutional overload. Citizens might vote on grain prices at dawn, judge a homicide at noon, and elect generals by dusk—too many decisions for any one brain.

Weaponised rumour. With no professional bureaucracy to vet intelligence, gossip outran evidence, steering policy before facts arrived.

The Afterglow and the Warnings

The restored democracy endured another seven decades—long enough for Aristotle to dissect its machinery in the Politics. By 322 BCE Macedonian regents dictated terms, and the once‑thundering ekklesia shrank to civic theatre. Yet Athens left two permanent gifts: the conviction that officials answer to audits, and the habit of giving ordinary citizens a direct stake in law.

The cautionary tales survive as well. A polity that links participation to pay must guard against turning voters into clients. Foreign adventures sold as pre‑emptive defence can mutate into imperial sinkholes that hollow civic virtue even if they enrich merchants. And most sobering of all: a people can vote their own power away, trading voice for promises of order, only to discover that oligarchy costs more than it claims.

Takeaways for Modern Citizens

Shared sacrifice breeds resilience. The fleet that crushed Persian hopes at Salamis was rowed by the poorest Athenians. Victories earned across classes knit society together; wars fought for narrow profit unravel it.

Checks outlast charisma. Pericles’ eloquence strengthened Athens because institutions hemmed him in. Once norms eroded, lesser orators weaponised the same stage. Durable safeguards must survive any single personality.

Democracy is a verb. Athenians recalibrated pay scales, jury sizes, and audit rules whenever reality shifted. Constitutions that fossilise risk snapping when pressure mounts.

Information quality is existential. Athens lost not only battles but the story war. Today’s algorithmic echo chambers replicate that danger at fibre‑optic speed. Citizens who prize evidence over rumour guard democracy’s heart.