On a mild spring morning in 2024, archaeologists in the rolling countryside of Tuscany found themselves peering into a darkness last touched over two millennia ago. A routine survey ahead of vineyard expansion had led to the unearthing of a sealed Etruscan tomb — its entrance blocked with cut stone, the chamber beyond untouched since antiquity. Inside, under the beam of work lamps, lay an array of grave goods: bronze mirrors with polished backs still catching the light, finely worked jewellery of gold and amber, and pottery arranged as if the funeral rites had ended only yesterday.

“It’s rare to find an Etruscan tomb this intact,” said excavation director Dr. Alessandra Conti, kneeling beside the entrance as the first artefacts were documented. “Grave robbing has been a problem here for centuries, so when we find one undisturbed, it’s like stepping into a story that was closed long ago.”

The Etruscans and their tombs

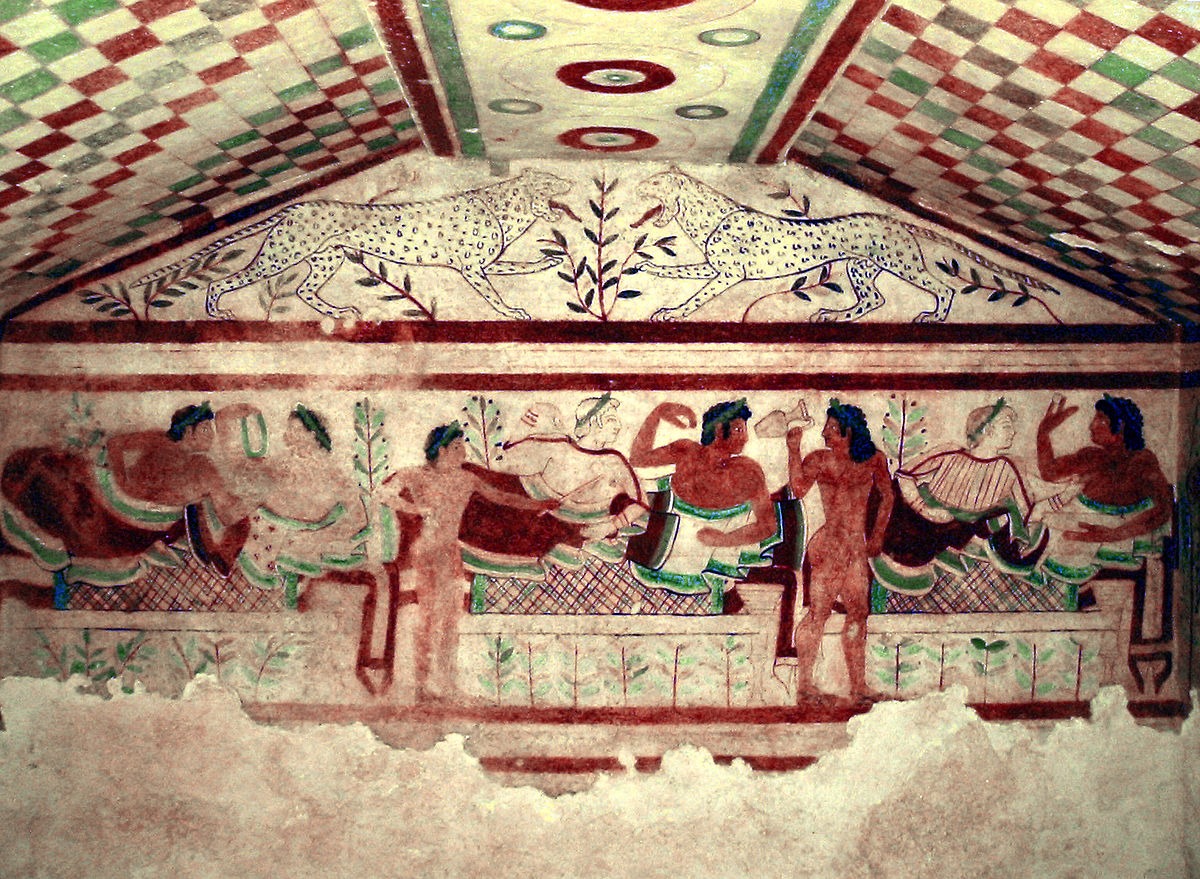

Between the 8th and 3rd centuries BC, the Etruscans dominated much of central Italy, building city-states that traded widely across the Mediterranean. Their tombs, often carved into rock or built as subterranean chambers, reflect a culture that placed high value on the afterlife. Walls were sometimes painted with banquets, dances, or mythological scenes; grave goods ranged from humble pottery to imported luxury items.

What makes this 2024 discovery exceptional is not just the preservation of objects, but their variety. Bronze mirrors, in particular, are a hallmark of Etruscan craftsmanship, often engraved with intricate scenes from mythology or daily life. Jewellery — delicate gold filigree, amber beads, and silver clasps — speaks to the status of the individual buried within, likely a woman of high rank.

Opening the chamber

The tomb lies on a gentle slope overlooking the Arno valley, near a cluster of known Etruscan sites but outside any mapped necropolis. The entrance was blocked by a slab of sandstone, sealed with a clay and lime mortar that crumbled at a touch. Once inside, the team found a rectangular chamber about four metres long, its floor lined with flat stone slabs. In the centre was a single stone sarcophagus, its lid still in place.

Grave goods were arranged in careful order: mirrors stacked near the head of the sarcophagus, jewellery laid out on a low wooden table (now collapsed but traceable from its fittings), and ceramic vessels clustered near the foot. Soil analysis suggests that organic offerings — perhaps food, textiles, or garlands — had long since decayed, leaving only faint stains and impressions.

Bronze mirrors: symbols and artistry

Etruscan bronze mirrors were both practical and symbolic. Polished to a high sheen, they reflected a clear image; on the reverse, artisans engraved scenes in exquisite detail. Some depict goddesses like Turan (Aphrodite), others show banquets, weddings, or even the toilette of noble women. In funerary contexts, mirrors may have served as talismans of beauty, status, and the continuation of identity into the afterlife.

Preliminary cleaning of the 2024 mirrors revealed at least two with figural decoration. One shows two seated women exchanging wreaths, a motif known from other Etruscan examples that may represent friendship or marriage bonds. Another appears to show a winged figure approaching a reclining man — possibly a scene from Etruscan interpretations of Greek myth.

Jewellery and personal adornment

The jewellery assemblage is no less revealing. Gold earrings shaped like grape clusters, strings of amber beads imported from the Baltic, and a silver fibula (brooch) point to wide-ranging trade connections. Amber was especially prized in Etruscan culture, associated with protection and divine favour. The craftsmanship is delicate, the gold worked into fine spirals and granulation that would challenge even modern jewellers.

The occupant of the tomb

The skeletal remains within the sarcophagus are currently undergoing osteological analysis. Early observations suggest an adult female, aged between 35 and 50 at the time of death. No obvious signs of trauma are present, and the bones are remarkably well preserved thanks to the tomb’s sealed environment.

Alongside the body, traces of organic material suggest the deceased was laid out on a wooden bier within the stone sarcophagus. Small bronze pins found near the shoulders may have fastened a shroud or cloak, while a pair of gold earrings still rested near the skull — a poignant survival of personal identity across centuries.

Context within Etruscan burial traditions

While the Etruscans often buried their dead with grave goods, the precise arrangement of this tomb’s contents is unusual. The clustering of mirrors and jewellery on one side, vessels on the other, and the absence of weapons or armour suggest a deliberate thematic separation — perhaps mirroring aspects of the deceased’s life or status. Similar patterns are known from elite female burials in sites like Tarquinia and Cerveteri, though the quality of the bronze work here is particularly high.

Dr. Conti notes that the find fits into a broader pattern emerging from recent excavations. “We’re seeing more evidence that women in Etruscan society could hold significant social and economic power. The goods in this tomb — especially the imported amber — speak to someone deeply connected to trade networks and cultural exchange.”

Preservation and conservation

Because the tomb had remained sealed, the metal objects retained much of their original surface detail. Conservators began immediate stabilisation, using microcrystalline wax to prevent rapid corrosion of the bronze mirrors. Gold and amber require different handling; the amber beads, in particular, are fragile after centuries underground and must be rehydrated slowly to avoid cracking.

The team is working in a temporary field lab near the site, photographing and cataloguing each item before moving them to the regional archaeological museum. There, a dedicated display will eventually reconstruct the tomb as it appeared at the time of excavation, offering the public a chance to step into the moment of discovery.

A window into Etruscan life and death

Grave goods like these are more than treasures; they are material biographies. The mirrors tell us about ideals of beauty and self-presentation; the jewellery maps networks of trade and craftsmanship; the ceramics reveal dining customs and possibly ritual practices. Together, they paint a picture of an individual who lived in a cosmopolitan, interconnected world — a reminder that the Etruscans were not an isolated culture, but active players in Mediterranean exchange.

For Dr. Conti, the find underscores the value of systematic survey and rescue archaeology. “If the vineyard expansion had gone ahead without investigation, this tomb might have been destroyed without anyone knowing. Every intact burial we find fills in another piece of the Etruscan puzzle.”

The broader significance of the 2024 discovery

The find comes amid a renewed focus on Etruscan archaeology, with several major exhibitions planned in Italy and abroad. In recent years, advances in DNA analysis and isotopic studies have added biological detail to the cultural picture, revealing migration patterns and diet. Now, intact tombs like this one are offering complementary evidence from the realm of material culture.

The mirrors and jewellery will undergo further study to determine their workshop origins. Stylistic analysis of the engravings may link them to known artisans or regional schools, while metallurgical testing could reveal the sources of the bronze and gold. Such information may help map the flow of raw materials and finished goods across Etruscan territory and beyond.

Looking ahead

The excavation is ongoing. Ground-penetrating radar has identified at least two more anomalies nearby that may represent additional tombs. If they too are intact, archaeologists could gain a rare view of an entire burial cluster, shedding light on family relationships, social hierarchies, and regional variation in funerary customs.

For now, the 2024 tomb stands as one of the most significant Etruscan finds of the decade — not because it changes the broad outline of history, but because it fills it with detail. The sheen of a mirror, the weight of a gold clasp, the curve of a ceramic vessel: these are the small certainties that bring the past into focus.

A conversation across time

Standing in the chamber, with the mirrors lined against one wall and the jewellery glinting under work lights, it is difficult not to feel a sense of presence. The person laid to rest here was seen, valued, and remembered by her community. In unsealing the tomb, the archaeologists have reopened a conversation interrupted for more than two thousand years — one that will now continue in museums, research papers, and the imaginations of those who stand before the artefacts.

As Dr. Conti put it on the day the last mirror was lifted from the soil: “These objects were made to last, and they have. Our task is to listen to what they still have to say.”