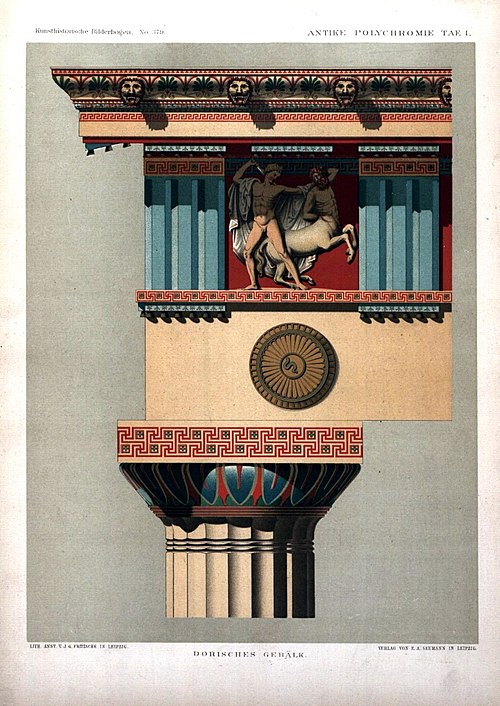

Stand beneath the Parthenon today and you see luminous marble, softened by time and light. That white is not the whole story. Ancient Athenians did not leave their most famous temple bare. They painted mouldings, triglyphs, metopes and sculpted figures with strong pigments that caught the sun. Recent scientific work and digital reconstructions have pushed this point from scholarly debate to vivid demonstration. The Parthenon was not pale. It was designed to glow.

What these reconstructions give us is not a carnival of guesswork, but a careful return to colour grounded in evidence. Portable instruments read microscopic traces in situ. Imaging techniques reveal pigments invisible to the eye. Once those clues are mapped, 3D models apply historically plausible palettes to the architecture and sculpture. The result is startling, yet rational. Lines we thought of as shadow become borders of blue. Patterns we barely noticed come forward in red and black. The building’s order tightens, and its symbolism reads more clearly from a distance.

What changed: from white-marble myth to a coloured reality

For centuries, the West admired classical ruins as studies in stone and light. That habit hid an ancient truth. Greek temples were built to be read, not merely admired. Colour guided the eye and marked out meaning. In the nineteenth century, a few scholars argued for ancient polychromy; modern conservation has turned suspicion into confirmation. On the Acropolis, researchers documented blue, red and other residues on architectural members. In the British Museum, imaging identified pigments on sculpture that once lined the cella.

Digital reconstructions do not replace the marble. They restore legibility. When a meander pattern along a cornice is tinted in its original blues, the movement of the design makes sense. When the sculpted figures of the frieze are given contrasting grounds, the procession becomes easier to follow. These reconstructions are models, open to revision, yet they already correct a long habit of viewing the Parthenon as a work of pure stone. Colour was part of the design language.

How scientists recover vanished paint

The work begins with the stone. Conservators and scientists take instruments up the scaffolds and examine surfaces under magnification. X-ray fluorescence identifies elements that hint at pigment families. Micro-Raman and FTIR spectroscopy provide molecular fingerprints. Visible-induced luminescence photography makes particles of Egyptian blue light up in the near-infrared, a party trick with serious value. Together, these methods tell you which colours were placed where, even when paint fragments are tiny or altered by weather.

Sampling is light-touch. The Parthenon is a global monument, so invasive work is kept to a minimum. Fortunately, a multi-technique approach often avoids the need to remove micro-samples at all. In several campaigns, teams recorded blue products along cornice blocks and decorative bands, reds in mouldings and details, and traces consistent with gilding on select areas. The picture is not complete, yet it is coherent enough to anchor reconstruction choices.

Which colours, and on which parts

Two blues do the heavy lifting in the surviving record: azurite and Egyptian blue. They were not interchangeable. Craftsmen used them for different zones and effects, sometimes side by side. Red appears as both ochre and, more rarely, the hotter cinnabar. Black gives definition in lines and patterns. Gold leaf or golden paint may have accented weapons, jewellery or border motifs in sculpture. No single scheme fits every block, because work proceeded over years and several hands. Still, patterns repeat: blue for the taenia bands and meanders; red for mutules and background fields; dark lines to sharpen relief.

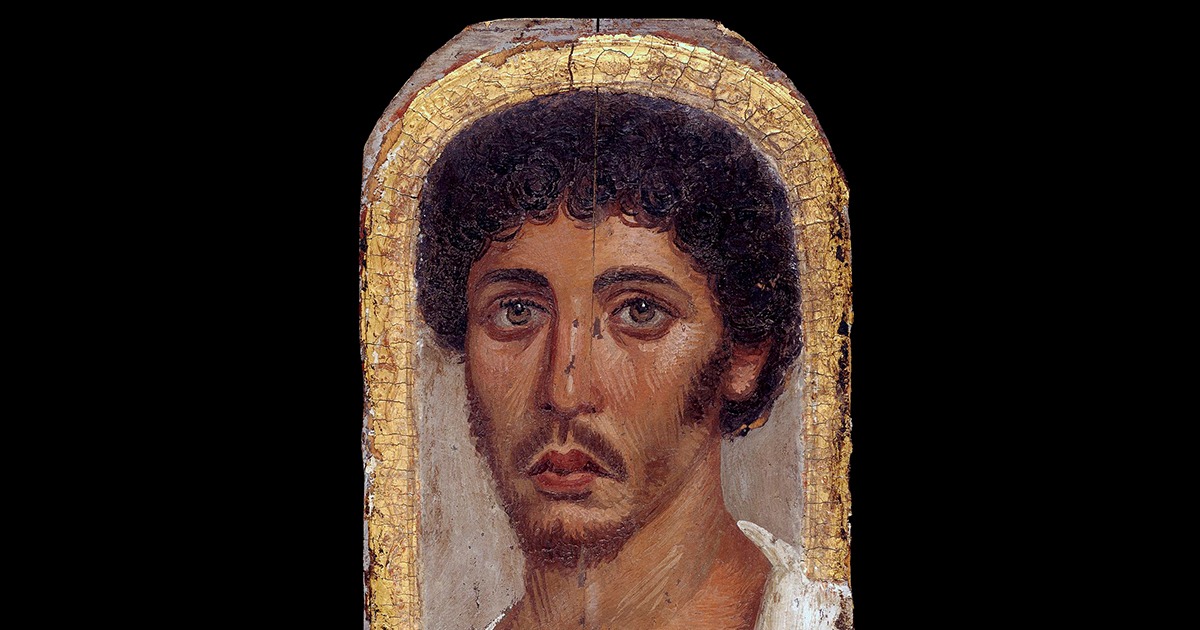

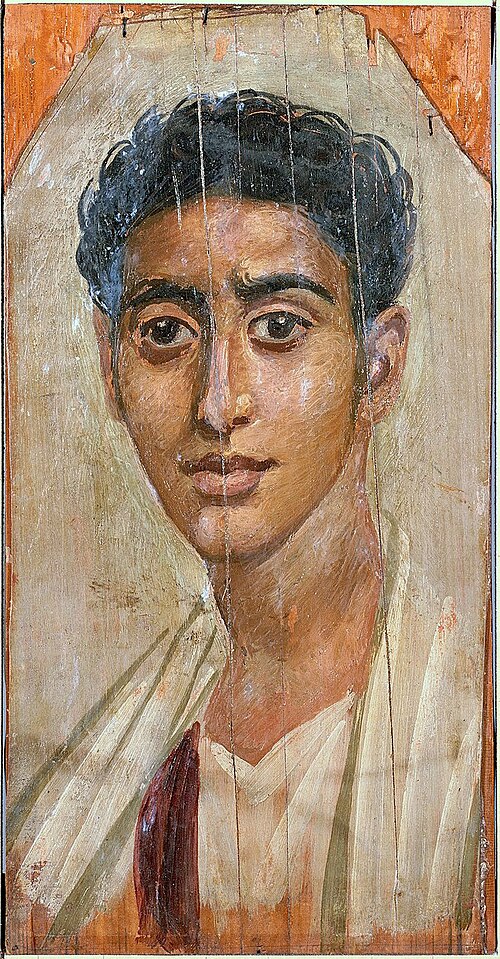

Sculpture complicates the story. Relief figures would have stood out against coloured grounds. Hair, eyes, lips and textiles took specific tints. Shields and harness might have had gilded details. Look at the west frieze today and imagine riders suddenly pulling forward from a blue-green field, with reins and manes picked out. The procession breathes again when the background returns.

Why the palette makes structural sense

Colour on Greek architecture is not decoration for its own sake. It clarifies structure and strengthens rhythm. On a bright day, white marble can dissolve under glare. A painted taenia reads as a clean baseline for the cornice. Coloured mutules cast shadows that seem deeper and more regular. Patterned bands arrest the eye before it slides away. The designers used pigment like an architect uses shade and light, to keep a large composition legible from far away.

There is also an optical trick at work. Egyptian blue scatters light in ways that remain lively even when the particles are small. Under Attic sun, a blue meander along the cornice would have flickered softly as you moved. Reds warm the stone; darks pull edges into focus. Reintroduce those effects digitally and the building’s proportions appear tauter. The refinements that scholars admire—the subtle curvatures and the precision of alignments—do not vanish. Colour helps you see them.

From data to digital: how reconstructions are built

Reconstruction teams combine several ingredients. First, they compile pigment maps from the analytical campaigns. Second, they collect high-resolution scans of architectural blocks and sculptures. Third, they examine historical watercolours and early casts that preserve details now lost. Those streams feed a 3D model. In software, conservators apply materials that simulate waxy or mineral paint, test saturation under simulated daylight, and iterate until the outcome aligns with the evidence. Each release is documented, so later research can update a tone, a border or a motif without starting over.

Two further limits keep the work honest. Where evidence is secure, colour placement is firm. Where evidence is thin, reconstructions show options or leave areas neutral. This blend of certainty and restraint is one reason the newest models feel persuasive. They do not shout. They guide.

What the sculptures may have looked like

Imagine a metope scene, Lapith against centaur. The stone carving gives motion and force. Paint adds the final read: a coloured ground behind the figures; darker lines to sharpen muscles; touches of red for wounds; gleam on a bronze cup or bit. Relief becomes narrative. On the frieze, human and animal eyes find definition. Hair takes depth. The parade looks less like a cloud and more like a sequence of real bodies moving along a wall.

Context from elsewhere: why other coloured sculptures matter

Some viewers hesitate when they see bright reconstructions. The tones feel modern to eyes trained on patinated stone. Comparanda help. Across Greek art, surviving paint and historical copies show that strong colour was the norm. Archaic statues wore patterned garments. Later pieces used subtler accents, but still relied on reds, blues and blacks to bring form into focus. When you study those cases, the Parthenon’s palette looks less like an exception and more like the best version of a wider habit.

Museum displays make this point well. Exhibitions that place a coloured replica next to an original give visitors a useful jolt. The white marble retains its quiet authority; the reconstruction explains how it once worked. You do not have to prefer one over the other. Seeing both together corrects the record.

Inside the temple: Athena Parthenos and spectacle

The exterior was not the only place where colour mattered. Inside stood Athena Parthenos, a colossal figure of gold and ivory, surrounded by painted architecture and glittering fittings. Modern replicas help us picture the effect. Gilded surfaces caught torchlight; coloured details framed the goddess; polished marble reflected both. Even if we disagree on exact shades, the principle stands. The interior was staged for impact, not stripped for minimalism.

This matters for how we think about sacred space. Ancient worshippers moved through a choreography of colour, texture and scale. The brighter palette of a reconstruction may look unfamiliar to us, yet it is closer to the ancient experience than a cool, unpainted hall. Digital models that include interior lighting deepen this insight. They show how the statue rose from darkness, how gold leaf glowed, and how painted ceilings gathered the light overhead.

Why this research changes public history

Colour is a cultural signal. When we drain it from classical monuments, we risk flattening the past into a single taste. The Parthenon’s original scheme tells us that Athenians valued clarity, splendour and legibility. It suggests a city at ease with saturated surfaces and strong patterns. That evidence also punctures a modern myth that white marble equals purity. The ancients were more practical and more theatrical than that idea allows.

Digital reconstructions can travel far beyond the hill in Athens. A teacher can load a model in a classroom and let pupils orbit the building, change the light and explore how a blue band shifts under midday sun. A museum can run a projection that overlays colour on a cast, so visitors see the linework snap into focus. These tools do not end debate. They open it to more eyes.

Questions people ask

How bright were the colours really?

Evidence says brighter than many expect. Reds and blues read clearly even at distance. Saturation varied with pigment and binder, and exposure would have mellowed surfaces over time. Reconstructions show fresh paint under ideal light. Reality on the Acropolis would have ranged from newly vivid to softly weathered, depending on maintenance and season.

Is there a risk of overconfidence?

Yes. That is why good reconstructions mark degrees of certainty. Some borders and motifs are anchored by traces and tool marks. Others rest on analogy with better preserved members or related buildings. Teams publish their choices so critics can test them. The models are not final words; they are well-argued drafts.

What about gold?

Gilding and golden paint likely accented small details rather than large fields on the outside. Inside, gold and ivory dominated the cult statue. On the exterior, gold’s job was to catch sun on a wreath, a weapon or a patterned band, not to turn the whole building into a mirror.

Seeing the Parthenon anew

If you visit, try this: look at a cornice block and imagine the taenia band filled with alternating blues. Let the meander sharpen into view. Look at a metope, and picture a coloured ground behind the figures. Then step back to take in the whole façade and sense how colour anchors form. The monument does not need paint to be great. Yet colour restores a register of meaning that the stone alone cannot supply.

Digital reconstructions will keep changing as new evidence arrives. That is a strength, not a flaw. Each season adds a small proof, a pigment trace, a border line. When those crumbs are collected in a model, the building we thought we knew becomes richer, more legible, and closer to what fifth-century Athenians saw when they climbed the hill.