Mythical Creatures A–Z: Origins, Symbols, and Ancient Sources is your clear, practical map through centuries of stories. The goal is simple: bring the best-known creatures into one guide, explain what each symbol meant in its original setting, and point you to the oldest texts or images where the creature first roared, hissed, or flew. You’ll find origins, core motifs, and ancient sources, all arranged A–Z, with concise notes you can use for research, teaching, or pure curiosity.

Read straight through or dip into a single letter. Either way, keep one rule in mind. Myth is local first and shared second. A dragon in Han China is not the same as a dragon on a medieval shield; a Greek sphinx asks riddles while the Egyptian sphinx guards kingship. Comparison helps, but context keeps the sense intact.

How to use this guide

Each entry follows a tight pattern: Origins (where the idea takes shape), Symbols (the imagery that carries meaning), and Ancient sources (texts, inscriptions, or objects you can actually look up). The aim is quick accuracy, not encyclopaedic sprawl. When in doubt, start with the oldest witness and read forward.

Mythical Creatures A–Z

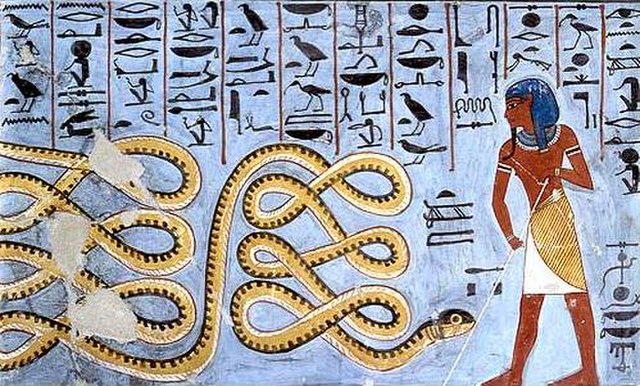

A — Apep (Apophis)

Origins: Ancient Egypt. Apep is the great serpent of chaos who attacks the sun god on his nightly journey. He belongs to a ritual world in which order must be renewed every day.

Symbols: Coiled snake, darkness, interruption; ritual defeat by spearing, burning, trampling. Apep represents the threat that never quite dies.

Ancient sources: Book of the Dead spells and temple texts; scenes of the serpent battled by Ra’s retinue appear on papyri and tomb walls.

B — Basilisk

Origins: Greco-Roman natural lore, later medieval bestiaries. The basilisk blends snake, rooster, and mythic venom. Medieval scribes turned the “little king” into a symbol of corrupt sight.

Symbols: Crowned snake or cockatrice; lethal gaze; enmity with the weasel. Used to warn against pride and bad rulers.

Ancient sources: Pliny’s Natural History mentions the basilisk; later bestiaries repeat and amplify the story with Christian moral glosses.

C — Centaur

Origins: Greece. Half-human, half-horse figures appear early in Greek art and story as tests of measure and civilisation. Think wild strength against civic order.

Symbols: Bow, club, wine; the struggle between appetite and restraint. The Lapith–Centaur battle became the classic image of culture versus chaos.

Ancient sources: Homer’s epics, Greek vase painting, and temple sculpture; later mythographers catalogue named centaurs and episodes.

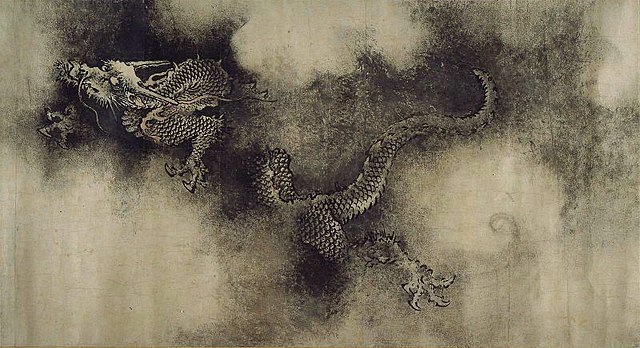

D — Dragon

Origins: Wide across Eurasia. In China, dragons bring rain and imperial fortune; in Greek and later European stories, drakōn shades into hoard-guarding monsters. The same word hides two very different symbolic families.

Symbols: Clouds, water, and luck in East Asia; treasure, test, and terror in the European Middle Ages.

Ancient sources: Han and Tang art for Chinese dragons; Greek epic and later folktale for European lines; Near Eastern serpent-slaying myths add deeper roots.

E — Echidna

Origins: Greece. The “mother of monsters” mates with Typhon and births a roster of trials for heroes: Cerberus, Hydra, Chimera, and more.

Symbols: Hybrid body; lair; motherhood as a generator of challenges, not comfort.

Ancient sources: Hesiod’s Theogony; later summaries by Apollodorus and artwork showing her offspring.

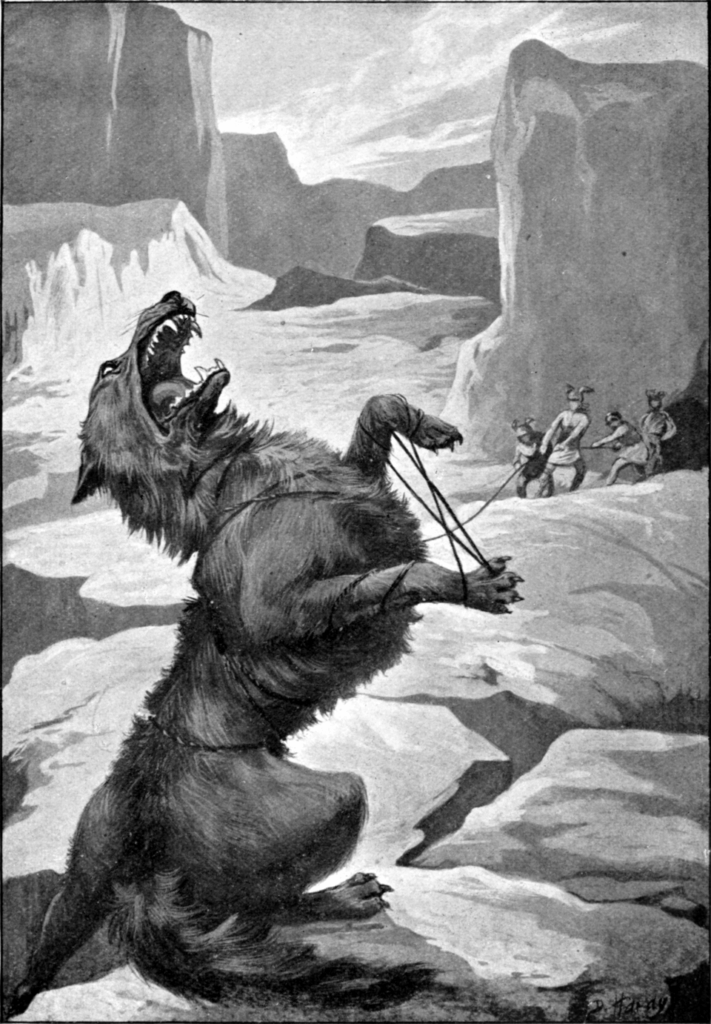

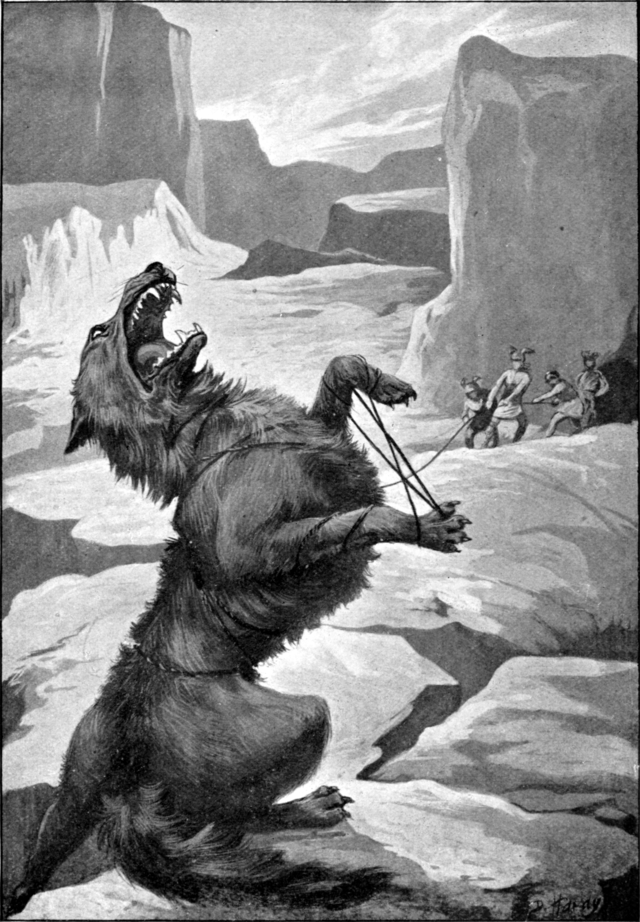

F — Fenrir

Origins: Norse. A vast wolf fated to kill Odin at Ragnarök. The gods bind him with a magical ribbon after tricking him into a test of strength.

Symbols: Binding and foreknowledge; the cost of delaying disaster. Fenrir personalises the risk that grows as you hide it.

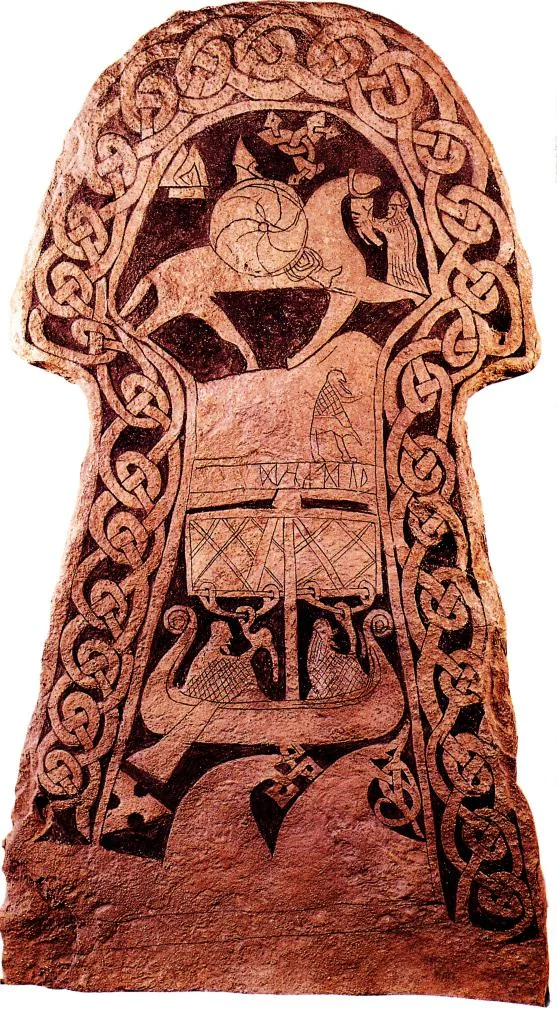

Ancient sources: Poetic Edda and Prose Edda; image stones and later art echo wolf-giant themes.

G — Gorgon (Medusa)

Origins: Greece. A protective horror: a face that turns back harm by turning it to stone. Medusa becomes a potent emblem on shields and buildings.

Symbols: Snakes for hair, staring eyes, tusked grin; later, a tragic beauty made mortal by a god’s anger.

Ancient sources: Homer and Hesiod mention Gorgons; archaic pottery and sculpture give the earliest full faces; classical copies like the Rondanini Medusa carry the image into Roman times.

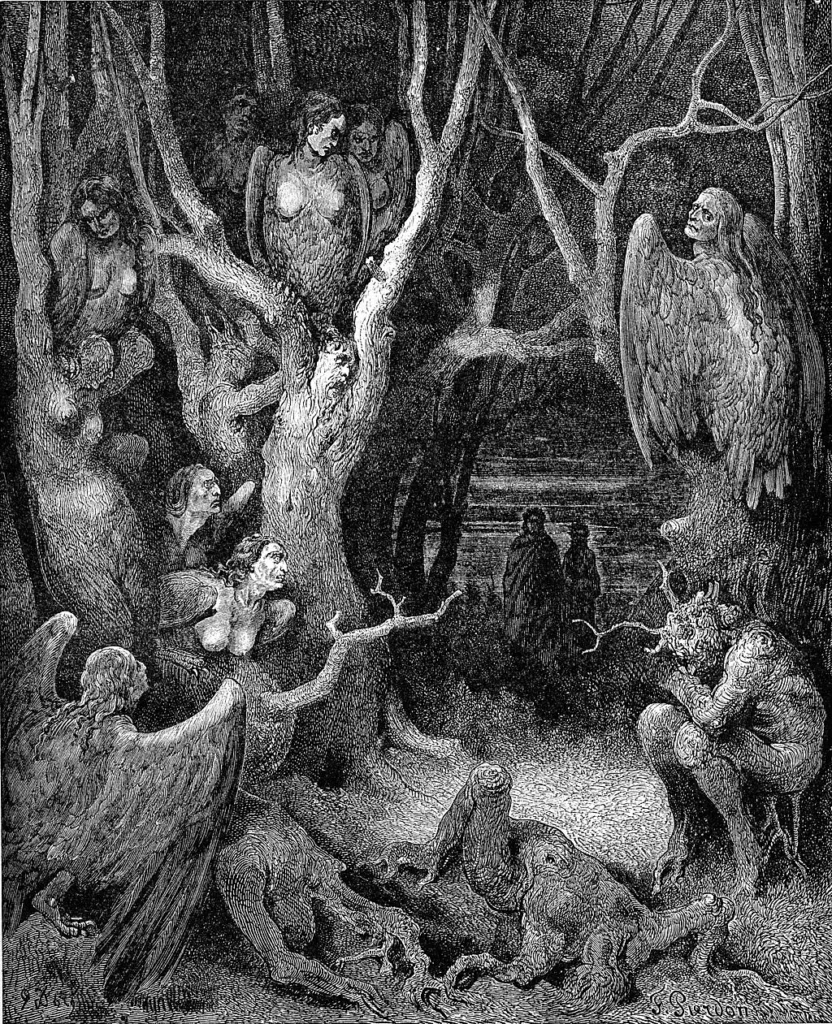

H — Harpy

Origins: Greek. Wind-spirits with claws, later moralised as snatchers of food or justice. In Lycia, winged female figures on tombs carry away small souls.

Symbols: Sudden deprivation, divine punishment, boundary between breath and body.

Ancient sources: Greek poetry for the name; Lycian “Harpy Tomb” reliefs for the striking funerary image.

I — Ichthyocentaur

Origins: Hellenistic and Roman art. Part human, part horse, part fish. Maritime cousins of centaurs appear on mosaics and luxury vessels.

Symbols: Sea mastery, hybrid grace, and the reach of Dionysiac imagery into the waves.

Ancient sources: Sculptures, gems, and mosaics; later descriptions organise the image into a type.

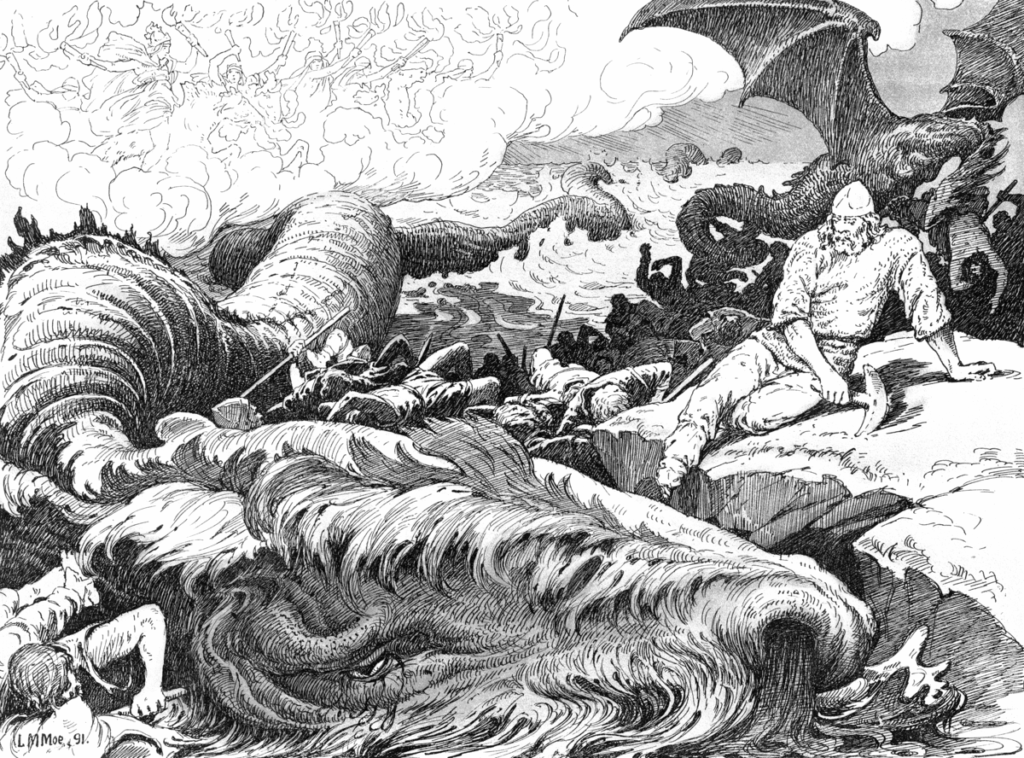

J — Jörmungandr (Midgard Serpent)

Origins: Norse. A world-girdling serpent fated to fight Thor. The fishing scene—hook, ox head, near-strike—shows courage, loss, and the danger of proud force.

Symbols: Ring, sea, horizon; the sense that what encircles the world also threatens it.

Ancient sources: Eddic poems and runestones with fishing scenes.

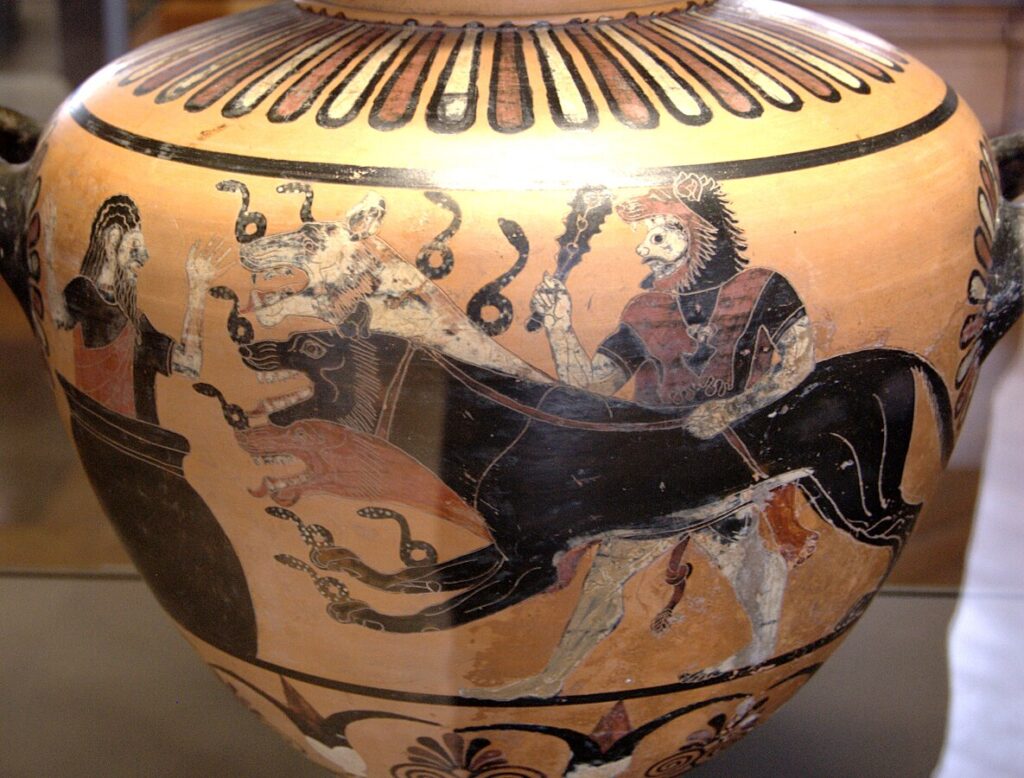

K — Kerberos (Cerberus)

Origins: Greece. The hound of Hades keeps the dead in and the living out. Herakles brings him to the light as his final labour.

Symbols: Multiple heads, snake elements, border control. Not evil; simply the rule of the underworld.

Ancient sources: Vase paintings across the archaic and classical periods; later Latin poetry reshapes the tone.

L — Lamia

Origins: Greek. A child-devouring monster in early tales; later a seductive predator linked to night terrors and sorcery.

Symbols: Appetite, deception, and fear of ungoverned desire.

Ancient sources: Diodorus and scholiasts; Roman poets keep the motif alive with new moral tones.

M — Minotaur

Origins: Crete and the Greek world. A human–bull hybrid in a man-made maze. Theseus’ victory rewrites a tribute system and claims heroic founding credit.

Symbols: Labyrinth, sacrifice, political myth. The thread and the turn mark intelligence over brute force.

Ancient sources: Attic vases, temple reliefs, and classical authors from Apollodorus to Ovid.

N — Nemean Lion

Origins: Greece. The first labour of Herakles. Skin too tough for weapons; strength and technique save the day.

Symbols: Invulnerable hide, new hero’s mantle. Later images show Herakles wearing the lion’s head as proof and protection.

Ancient sources: Vase paintings and early mythographers; the motif anchors the hero’s identity.

O — Orthrus (Orthos)

Origins: Greece. A two-headed watchdog, sibling to Cerberus. Killed by Herakles during the cattle raid of Geryon.

Symbols: Guardianship, doubling, and the chain of labours.

Ancient sources: Hesiod; black-figure vases show the scene with Geryon and Eurytion.

P — Phoenix

Origins: Greek and Egyptian cross-currents; later Roman art loves the rebirth image. A single bird renews itself from ashes or fire.

Symbols: Cycles, empire’s resilience, personal renewal. In late antiquity, a Christian metaphor for resurrection.

Ancient sources: Herodotus mentions a strange bird; Roman mosaics give the most durable iconography.

Q — Qilin

Origins: China. An auspicious hooved creature linked to wise rule and peaceful ages. Sometimes dragon-scaled, sometimes deer-like, always gentle.

Symbols: Benevolent power, harmony, and the appearance of sages. A counter-image to the threatening monster.

Ancient sources: Early Chinese texts and art; later depictions evolve with court style and regional taste.

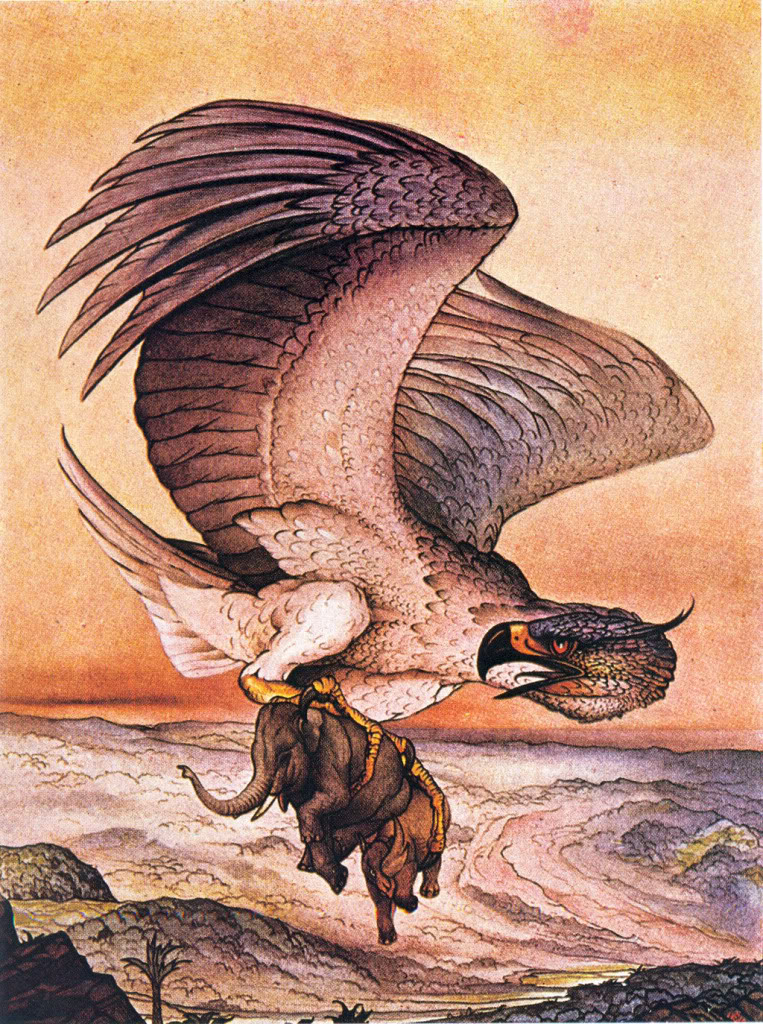

R — Roc

Origins: Persian and Arabic storytelling. A colossal bird capable of lifting elephants, best known from later travel tales.

Symbols: Scale, wonder, distance. The Roc marks the horizon of the known world.

Ancient sources: Medieval Arabic literature and Persian epics; the motif fuses with Indian and Near Eastern giant-bird lore.

S — Sphinx

Origins: Two families. Egyptian sphinxes are royal guardians with a lion’s body and a human (often kingly) head. Greek sphinxes are riddle-setters that test and punish.

Symbols: Thresholds, knowledge, authority. The same body speaks two languages depending on landscape and law.

Ancient sources: Egyptian temple avenues; Greek pottery and the Oedipus cycle for the questioning form.

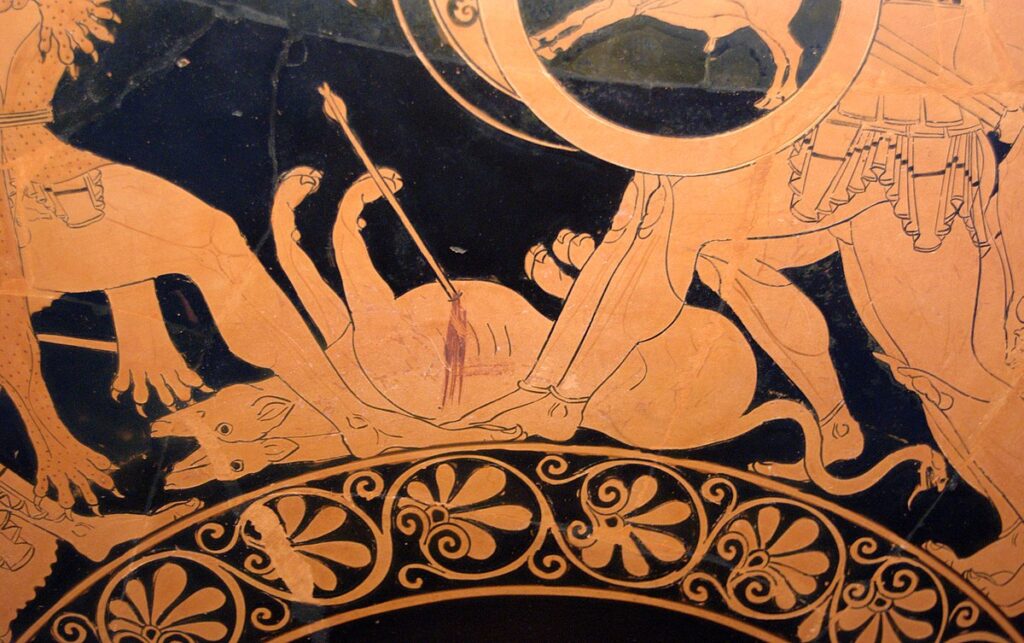

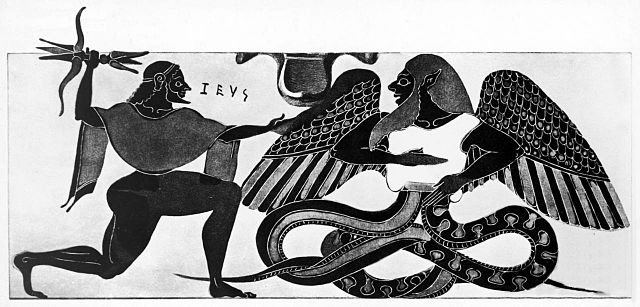

T — Typhon

Origins: Greece. A storm-giant who challenges Zeus after the Titanomachy. In some accounts, he maims the king of gods before lightning wins the day.

Symbols: Volcano, storm, panic. Typhon carries the fear of nature’s counterattack.

Ancient sources: Hesiod; Hellenistic retellings stress the geography of defeat.

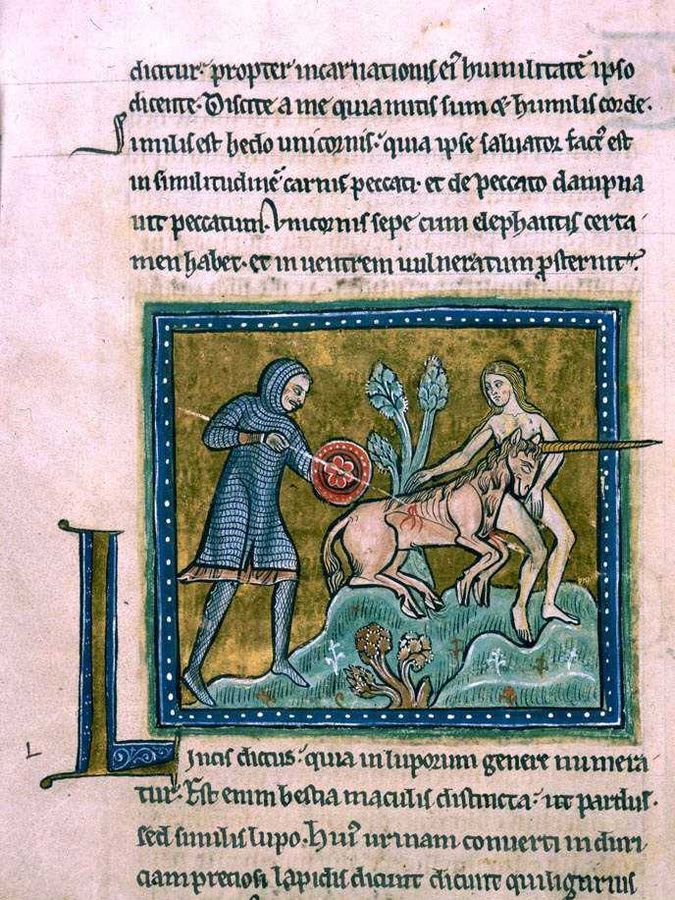

U — Unicorn

Origins: Greek reports of Indian animals meet Near Eastern motifs; medieval Europe moralises the image into purity captured by a maiden.

Symbols: Single horn, healing, difficult taming. The unicorn measures the worth of desire and the risk of capture.

Ancient sources: Ctesias and later compilers; bestiary illuminations fix the modern look.

V — Valkyrie

Origins: Norse. Choosers of the slain who gather the worthy to Odin’s hall. Not monsters, yet creatures of fate who ride between battle and banquet.

Symbols: Ravens, spears, horses; service and selection; the honour of a death that serves the group.

Ancient sources: Eddas and skaldic verse; picture stones may show their welcome gestures.

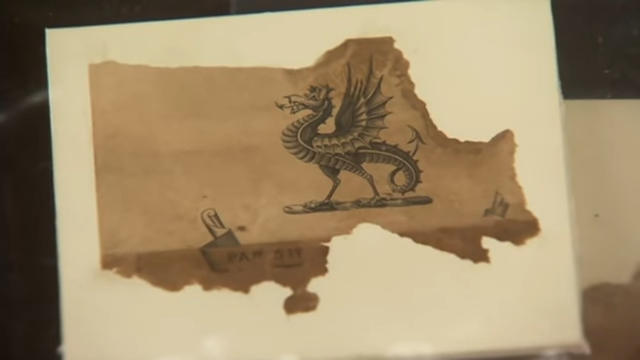

W — Wyvern

Origins: Europe. A two-legged dragon in heraldry and later romance. Lighter than the full four-legged dragon, quicker in line and symbol.

Symbols: Warning, warding, and local identity. Town crests love a crisp silhouette.

Ancient sources: Medieval armorials and carvings; the type stabilises in heraldic manuals.

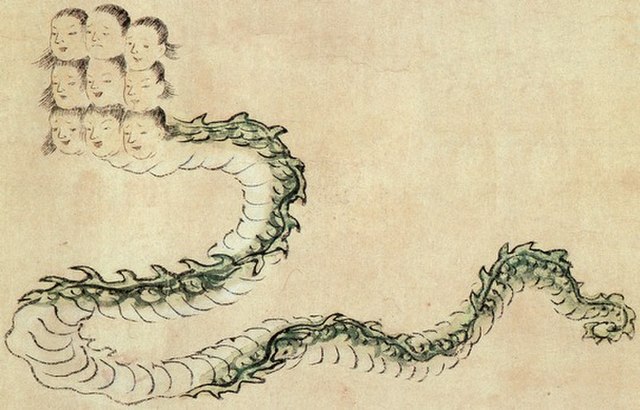

X — Xiangliu

Origins: China. A nine-headed serpent associated with floods and devastation; the inverse of the orderly, auspicious dragon.

Symbols: Excess, overflow, the many-mouthed disaster; water as threat rather than blessing.

Ancient sources: Early Chinese mythic compilations; later art alludes to the tangle rather than literal heads.

Y — Yeti

Origins: Himalayan folklore. A wild, man-like figure tied to snowfields and fear of the high places. The modern “Abominable Snowman” is a Western recast.

Symbols: Cold, awe, frontier; also the danger of forcing proof on stories meant to carry warnings rather than measurements.

Ancient sources: Traditional accounts; colonial-era retellings distort tone—treat with care.

Z — Ziz

Origins: Jewish lore. A cosmic bird paired with Behemoth and Leviathan, mapped onto creation’s edges. Rare in art, rich in theological play.

Symbols: Scale, sheltering wings, the idea that sky itself can be a creature.

Ancient sources: Midrashic and medieval texts more than classical sculpture; the name circles wider Near Eastern giant-bird traditions.

Quick cross-links and motifs

Serpents and order: Apep and Jörmungandr mark the edge where order meets the deep. One attacks nightly; one encircles the world. Both keep heroes honest.

Hybrid warnings: Centaur, Sphinx, Lamia, and Ichthyocentaur test the line between skill and appetite. Hybrids teach balance by showing its breach.

Birds of meaning: Phoenix promises renewal; Roc draws a horizon; Ziz fills the sky with theology.

Hounds and gates: Kerberos and Orthrus enforce borders. Passing them is a rite of status, not a prank.

How to read creatures well

Start with the oldest witness you can find. Ask what work the creature does in its home culture: protects, punishes, tests, or teaches. Then watch for change. Later ages repaint dragons as enemies, sphinxes as riddles, unicorns as moral puzzles. The moves are instructive. They show what people needed the creature to do next.

Further looking (images you can trust)

Museum and archive images carry context and stable credits. Use the links in the figure captions above, and explore the parent collections for related objects. You’ll spot motifs repeating across pots, stones, and pages. That is myth doing its work.