Among the Norse myths preserved in medieval Icelandic prose and verse, the binding of Fenrir is one of the most vivid. At the centre is a wolf so immense that his jaws could swallow the sky. Around him gather the Æsir, the ruling gods of Asgard, who fear what prophecy says he will become. Their solution is not to kill him outright, but to restrain him with cunning. The episode reads as high drama, full of trickery, defiance, and loss. Yet it also works as an allegory for political fears — a story about the dangers of power left unchecked, and the unease rulers feel toward forces they cannot wholly control.

Fenrir’s legend is preserved in the Poetic Edda and Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda, both written down in Christian Iceland but drawing on older oral traditions. In these accounts, the wolf is fated to break free at Ragnarök, killing Odin before being slain by Odin’s son Víðarr. Until then, the gods watch him grow. They decide to act while the threat can still be managed. This balance of present restraint and future fear makes the tale more than a simple monster story — it is about politics in a mythic register.

Who is Fenrir?

Fenrir, also called Fenrisúlfr, is one of the children of the trickster Loki and the giantess Angrboða. His siblings are the world-serpent Jörmungandr and Hel, queen of the dead. All three are marked by fate as dangerous to the gods. The wolf grows up in Asgard under the wary eyes of the Æsir. Only the god Týr dares to feed him directly. His appetite and strength expand at an unnatural rate. By the time the binding takes place, Fenrir has become too great to ignore.

Descriptions of Fenrir vary in detail but agree on his scale and ferocity. His mere presence unsettles the gods. Prophecy, in Norse myth, is not to be taken lightly. If seers have spoken of disaster, the wise move is to prepare. That, at least, is the logic the Æsir follow when they set their plan in motion.

The first chains

The gods begin with open tests. They forge a great fetter called Læding and invite Fenrir to try his strength against it. The wolf, confident, allows the attempt. He snaps the chain with ease. A second, heavier fetter named Dromi is brought out. Again, he consents, again he breaks it. These trials serve both as plot and as parable. Power that defeats ordinary bonds demands extraordinary measures.

In political terms, these early chains are like the laws or agreements that restrain a rising power at first but soon prove inadequate. The act of testing becomes part of the threat — each failure to hold him only proves his growth.

Gleipnir: the impossible restraint

Recognising that no ordinary chain will suffice, the gods turn to the dwarves of Svartálfaheimr, master smiths of impossible things. The dwarves craft Gleipnir, a ribbon-thin fetter woven from six paradoxical ingredients: the sound of a cat’s footfall, a woman’s beard, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird. Each is something that does not exist, yet in the dwarves’ forge these impossibilities take form.

The symbolism is layered. Gleipnir’s components are intangible, elusive, and improbable. As an allegory, it is the kind of constraint that power cannot easily prepare for — not a visible fortress or weapon, but a network of subtle measures woven from unlikely sources.

The wager and the bite

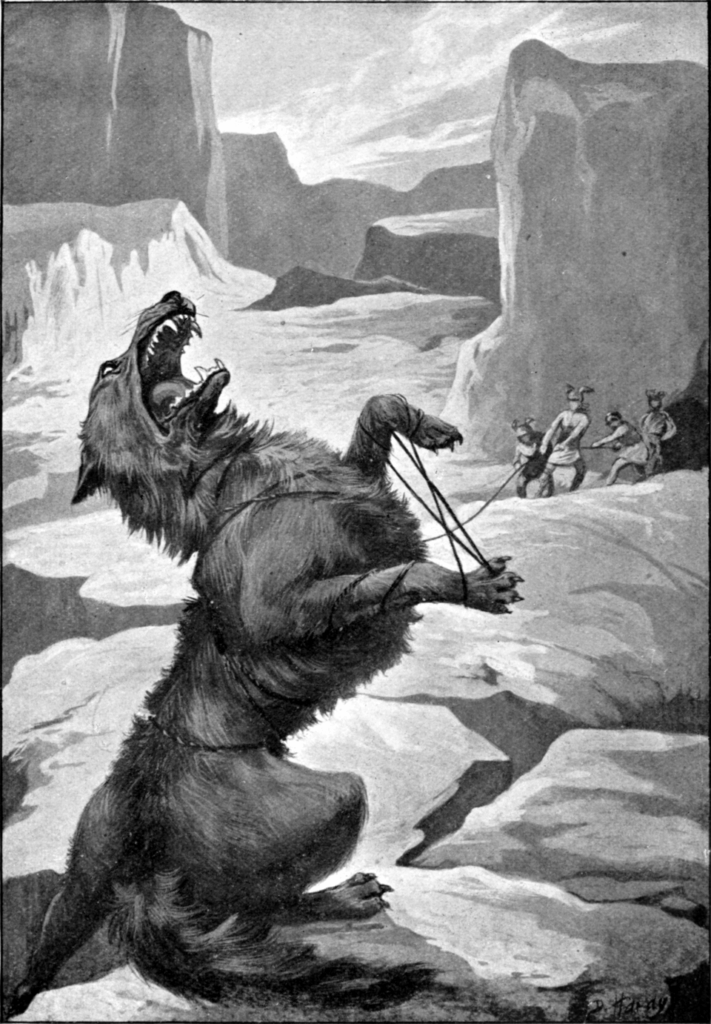

When the gods present Gleipnir, Fenrir grows suspicious. It looks too slight to be serious, and in myth, appearances often deceive. He agrees to the binding only if one of them will place a hand in his mouth as a pledge of good faith. Týr steps forward. As soon as Fenrir finds he cannot break the fetter, he bites down, taking Týr’s hand. The price of securing the wolf is a permanent loss to the god who dared to deal honestly.

This is one of the most recognisable scenes in Norse art and literature. It is also the moment where the allegory sharpens. Binding a dangerous force often requires sacrifice from those who value justice. The fetter holds, but trust is gone.

Fenrir as political allegory

Read in the halls of medieval chieftains, the binding story resonates beyond the fate of one wolf. Fenrir can stand for any force — a rival clan, an ambitious warrior, a dangerous idea — that grows too strong to ignore. The first attempts to restrain it may fail, feeding its confidence. Only an extraordinary strategy, prepared with skill and secrecy, can contain it. Even then, those who commit to the task may pay a personal price.

This framing makes sense in the political culture of the Norse sagas, where alliances shift, oaths matter, and unchecked power threatens stability. The gods do not kill Fenrir when they have the chance, perhaps because outright destruction carries its own risks. Instead, they bind him, knowing the act will only delay the foretold battle. It is a choice between managing a threat and igniting immediate chaos — a choice rulers have faced in many times and places.

Fear of tyranny, fear of chaos

In political allegory, Fenrir’s growth mirrors the rise of a tyrant. At first, his appetite may be tolerated, even indulged, if it serves the rulers’ needs. Eventually, his ambitions threaten the system itself. The gods’ fear is not only of his strength, but of what that strength could do to the order they embody. The binding, then, is an assertion of collective authority over a force that could dominate them all.

The allegory cuts both ways. For those wary of concentrated power, the gods’ decision to restrain a being pre-emptively could itself be read as tyranny — the powerful conspiring to neutralise a threat before it acts. This tension gives the myth its enduring bite.

The role of prophecy

In Norse myth, prophecy is a frame, not a chain. The gods act because they believe the seers. Fenrir will kill Odin. The binding can only postpone the event. This inevitability shifts the story from a simple victory into a holding action. Political systems often work this way — they cannot eliminate risk entirely, but they can try to manage its timing.

The decision to bind rather than kill also suggests that even dangerous power has uses. Until Ragnarök, Fenrir’s existence is a known quantity, his place fixed. Unbound, he would be unpredictable. Bound, he is part of the structure, even if that structure must be reinforced with care.

Týr’s role and the cost of honour

Týr’s sacrifice is more than a personal act of courage. It shows that in any collective decision to restrain a threat, someone must bear the cost directly. In the sagas, such figures are often the most respected — those who keep their word even when it hurts. Týr’s loss is permanent, a reminder that political solutions leave marks on the individuals who make them possible.

That the other gods do not volunteer speaks to another truth: collective interest does not mean equal risk. In many systems, the burden falls on the one willing to face the danger head-on, while others benefit from a safer distance.

Modern echoes

The binding of Fenrir appears in political commentary even today, invoked as a metaphor for pre-emptive action against rising powers, from individuals to institutions. In literature, it surfaces when authors explore the tension between liberty and security, or between feared potential and actual wrongdoing. The fact that the myth ends with the wolf breaking free keeps the metaphor honest. No binding lasts forever. Vigilance is not a one-time act.

Artists return to the image of the bound wolf because it holds a perfect balance of tension and stillness. It asks whether the moment is one of safety or of danger held in abeyance. That ambiguity keeps it alive in the cultural imagination.

Why not kill him?

Readers often ask why the gods did not simply kill Fenrir. The Eddas do not give a definitive answer. Perhaps they feared the reaction of Loki or the giants. Perhaps killing him would fulfil the prophecy in a worse way. In political allegory, outright destruction of a rival often destabilises the system more than containment does. A bound rival can serve as a warning or a scapegoat. A dead one leaves a power vacuum.

This ambiguity leaves room for interpretation, which is one reason the story survives retelling in contexts far removed from Viking Age Scandinavia.

The imagery of binding

Binding, in Norse myth, is a potent act. It appears in the fetters placed on Loki, the chains that hold the serpent until Ragnarök, and the magical snares in heroic sagas. It is both physical and magical, a visible sign of control backed by unseen force. Gleipnir’s ribbon form adds to the effect — the strongest fetter looks like nothing. In political terms, the most effective restraints are often invisible to those outside the circle of power.

Fenrir’s place in the larger myth cycle

The binding is only one chapter. At Ragnarök, Fenrir breaks free. He swallows Odin whole. Víðarr avenges his father by tearing the wolf apart. The sequence underscores that the gods’ measures only bought time. In political allegory, this is the moment when restrained power finally bursts its bonds, often in crisis. The delay still matters — years of relative stability can be the difference between survival and collapse.

Between binding and breaking lies the long watch. The gods live with the knowledge of the wolf’s presence, his jaws waiting. Managing that watch is itself a form of governance.

From myth to meeting-hall

In Viking Age society, stories like this could be recited in the longhouse as both entertainment and counsel. A chieftain might hear in it the reminder to check rising ambition in his own circle. A poet might use it to caution against delaying too long. The wolf, once bound, also symbolises enemies contained — proof of the ruler’s strength and foresight.

Like many Norse myths, Fenrir’s binding gains its force from being both specific and open-ended. The details anchor it in a world of gods, giants, and magical dwarves. The structure lets it travel into political metaphors centuries later.

A closing reflection

Fenrir’s binding is more than a monster’s capture. It is a meditation on power, fear, and the cost of keeping danger in check. The gods act together, but the price falls on one. They win the day, but not the future. They weave the perfect restraint, but from things that should not exist. And still, the prophecy waits. For anyone who has faced the challenge of restraining a force too strong to ignore, the image of the bound wolf, jaws ready, eyes bright, remains as sharp as when the skalds first sang it.