Two City‑States, Two Visions of the Good Life

A narrow ribbon of water—the Gulf of Corinth—separates the stony Peloponnese from the wider plains of Attica, yet within that short sail ancient Greece produced two societies as different as iron and marble. Sparta valued order above imagination, forging citizens who marched in silent columns and measured honour by wounds. Athens, in contrast, made conversation a civic duty; to live well, said an Athenian, was to argue in the agora and leave a mark on stone, stage, or parchment. The clash between these visions shaped classical history, but it also framed an enduring debate: how much freedom can a people enjoy without jeopardising security, and how much discipline can they impose without choking the human spirit?

Spartan Republic of Spears

Sparta’s chronicle begins far from warm coastlines, beside the chill Eurotas River. Dorian settlers subdued an earlier Mycenaean population and, over generations, bound the fertile valley to a military machine. At birth every boy faced inspection by a council of elders; those judged frail met exposure on Mount Taygetus. Survivors entered the agōgē, the famously savage training pipeline that lasted from age seven until thirty. Boys learned to endure cold, hunger, and public ridicule; whipping contests at the shrine of Artemis Orthia left backs striped like sanded wood. Stealing food was encouraged—getting caught earned a beating, not for theft itself but for clumsiness.

The political structure mirrored the phalanx: rigid yet internally balanced. Two hereditary kings marshalled armies, a gerousia of twenty‑eight elders proposed laws, and five annually elected ephors enforced them—sometimes arresting kings who strayed. But the glittering shields rested on darker foundations. For every Spartan citizen (homoios, “equal”) there were at least seven helots, an enslaved people bound to the land. Annual krypteia patrols let teenage boys murder suspected rebels, terror disguised as rite of passage. Fear of uprising kept hoplites close to home, discouraging prolonged overseas adventures until Persian gold briefly loosened the leash.

The Athenian Experiment in Creative Freedom

Athens, perched on rocky Attica and fronting the Saronic Gulf, could not feed itself without trade. Sea lanes brought timber from Thrace, grain from the Black Sea, and ideas from everywhere. Economic necessity pushed political innovation. In 508 BCE Cleisthenes reorganised citizens into mixed tribes that spanned city, coast, and inland villages, diluting the old clan monopolies. Over the next century stipends for jurors, payment for naval service, and rotation of public offices by lot (sortition) widened participation far beyond what the Peloponnese would tolerate.

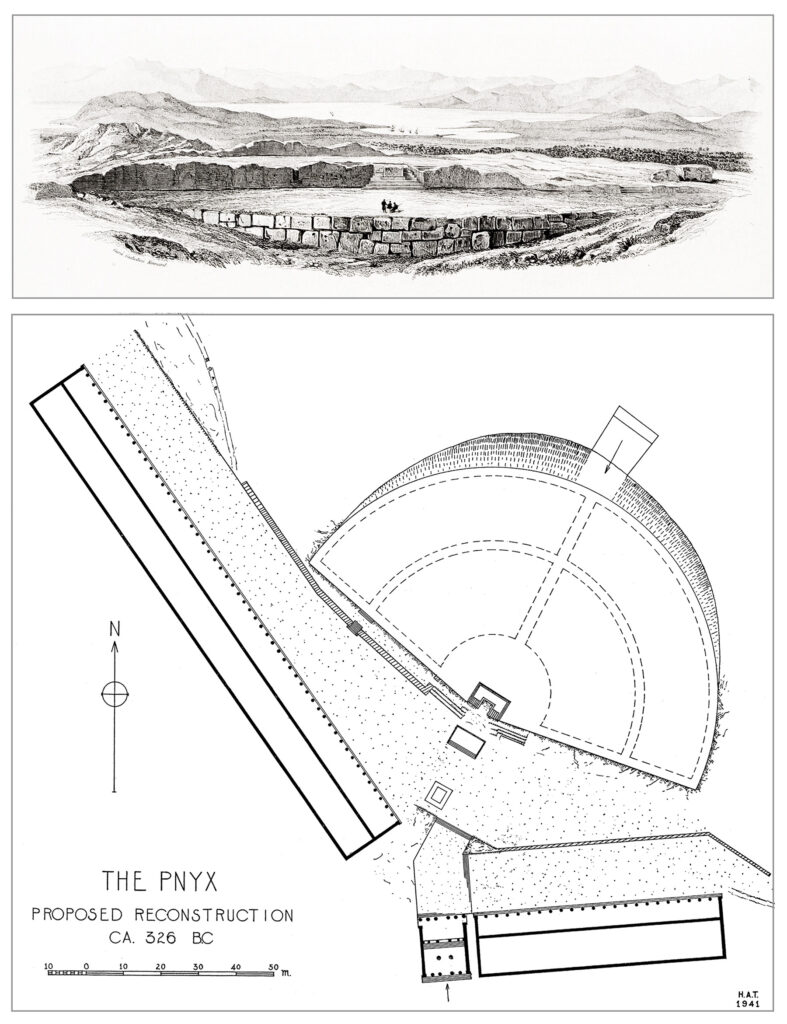

The assembly met on the Pnyx, a windswept hill where as many as 6 000 voices could vote by show of hands. Rhetoric became survival gear; a farmer who argued persuasively might pass a decree before ploughing the afternoon field. Meanwhile, the Long Walls linked Athens to its port at Piraeus, turning sea power into lifeline. Art flowered under this umbrella of security: Phidias raised marble giants, Sophocles probed moral tragedy, and Herodotus invented narrative history. Metics—resident foreigners—could never be citizens, yet they ran banks and crafted red‑figure pottery that still dazzles museum vitrines. Slavery existed, but a slave might earn freedom or manage a silver mine for wages, degrees of mobility unthinkable in Sparta.

When Shields and Scrolls Collided

Persia’s invasions in 490 and 480 BCE forced the rivals into uneasy partnership. Spartan hoplites died holding Thermopylae’s narrow pass while Athenian triremes gutted Xerxes’ navy at Salamis. Victory inflated both egos—and ambitions. Athens transformed the Delian League from defensive pact into fiscal empire, transferring the league treasury from Delos to the Parthenon’s shadow. Island allies paid tribute in silver or ships; dissent invited forced “democratisation” at spear‑point.

Sparta, fearing encirclement, formed the Peloponnesian League and watched Athenian walls grow like marble spears around a neighbour’s house. Thucydides diagnosed the coming storm: “What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.” When hostilities erupted in 431 BCE, strategies mirrored values. Sparta’s hoplites ravaged Attic farms each summer, confident that ruined harvests would break morale. Athens stayed behind stone and disease: plague killed perhaps one‑quarter of her citizens, including Pericles, the city’s guiding mind. Yet the navy raided Peloponnesian coasts, capturing slaves and disrupting harvests.

Turning points arrived thick and grim. In 425 BCE Athenian marines captured 120 Spartans on Sphacteria—proof the “invincible” could surrender. In 415 BCE Athens, drunk on confidence, launched the Sicilian Expedition: 200 ships, 30 000 men, and dreams of another grain basket. Syracuse annihilated the armada; prisoners died in stone quarries. Sparta seized the moment, cut Athenian grain routes at Hellespont with a Persian‑funded fleet, and captured Decelea to strangle silver‑mine income. In 404 BCE, starving and exhausted, Athens lowered her walls to Spartan trumpets. A puppet oligarchy—the Thirty Tyrants—purged opponents until a citizen army restored democracy within a year, but the city’s empire was dust.

Twin Legacies Written in Dust and Stone

Sparta’s rigid order won wars but bequeathed little beyond tactics and cautionary tales. The demographic base—never large—shrank as landholdings concentrated in female inheritance and citizen rolls dwindled. When Theban general Epaminondas shattered a Spartan army at Leuctra in 371 BCE, the myth of invincibility evaporated; helots seized the moment to revolt, and the city slipped to regional footnote.

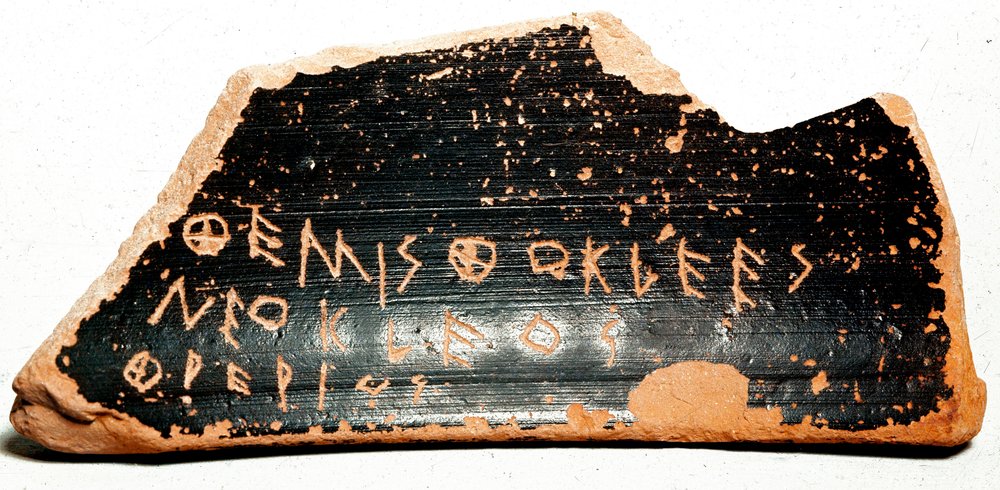

Athens, though humbled militarily, rebounded as intellectual beacon. Its schools educated Macedonian princes, its drama toured Italian colonies, and its legal concepts—trial by jury, audit of officials, ostracism as safety valve—infiltrated Roman law. While Sparta inspired later militarists—from Roman moralists to Prussian drillmasters—Athens seeded the vocabulary of citizenship. Philosophers who once mocked politicians became textbooks for them: Socrates’ gadfly stance, Plato’s philosopher‑king ideal, Aristotle’s mixed constitution all entered Western canon.

Lessons for Today

- Discipline without openness breeds stagnation. Sparta’s suspicion of trade and innovation made it formidable in war but brittle in peace; economies thrive on exchange, not isolation.

- Freedom without foresight invites overreach. Athens’ creative ferment funded marvels yet also financed reckless ventures like Sicily, proving that booming revenue can intoxicate decision‑makers.

- Security and culture must co‑evolve. A society that channels all surplus into spears or all surplus into statues risks imbalance. Durable greatness mixes shield and scroll.

- Power rests on narrative. Spartans called themselves the “wall of Greece” to legitimise austerity; Athenians styled their empire a “league” to mask tribute. Modern states likewise frame policies in protective myths.

- Legacy lives in ideas, not borders. Sparta left a model of discipline; Athens left dialogue, drama, and democratic aspiration. Which echoes louder across millennia?