Every army fears the enemy it can’t outmarch: weather. In the Teutoburg Forest, wind and rain did what spears could not do alone. They loosened boots, soaked shield leather, clogged wheels, deadened bowstrings, and turned a tightly drilled column into a broken file of stragglers. The Germanic coalition under Arminius knew that misery spreads faster than orders in a storm. They chose their ground, watched the sky, and waited for the moment when nature would do the opening work. Then they closed in.

The set-up to the disaster is well known. Publius Quinctilius Varus, governor of the new Roman province east of the Rhine, prepared to march his legions back to winter quarters. On paper it was straightforward — a long column following forest tracks, baggage in tow, auxiliaries on the flanks, routine halts for camp. Yet the countryside was not empty. Tribal leaders had read Roman habits all summer. They understood the roads, the bottlenecks, the gullies and marsh fringes, and the comfort Roman officers took in timetables. Most of all, they understood the sky. Autumn weather in northern Germania can turn savage without much warning. That is exactly when the ambush was sprung.

Weather as a weapon, terrain as the trigger

Bad weather by itself doesn’t kill legions; it exposes their seams. A Roman marching column worked like a machine so long as the road stayed dry and the order of march held: scouts ahead, engineers to cut a way through trees, then units in blocks, then baggage, then followers. Heavy rain and cross-winds break that rhythm. Mud forces wagons to swerve into the verge, oxen balk, the pace slows, and the column stretches. Officers have to choose: keep halting to re-close the intervals — or push on and accept gaps. Either choice hurts. Halting hands the initiative to the enemy; pushing on leaves units isolated.

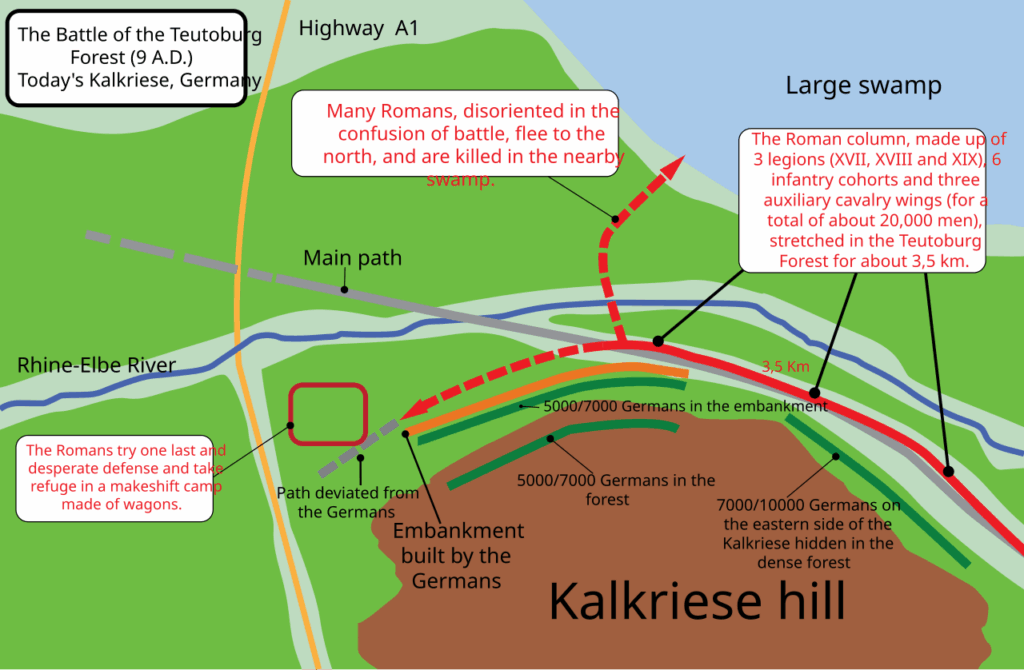

Arminius’s fighters exploited that predictable hesitation. They did not stand in open ranks; they used banks and hedges and the forest’s press of trunks. The plan was simple: attack the column at multiple points, then vanish into cover before the reply could form. In rain, that reply took even longer. Dripping cloaks, waterlogged packs, and slippery ground slowed the act of transforming from march to battle line. Shields grew heavier; pila throws lost snap; signal horns carried poorly in the wind. When the Romans reached a narrow shelf of ground with bog to the left and a rise to the right, the coalition sealed the trap with a fieldwork — a slashing length of earthen rampart behind which javelins and stones could be hurled with vicious effect.

How rain, wind, and mud tilt a fight

Soldiers talk endlessly about “friction” — the small things that jam the big plan. Teutoburg’s friction reads like a catalogue of wet-weather failure. The road surface, churned by hooves and wheels, became a series of slick ruts that twisted ankles and collapsed files. Shield facings took on water; their wood cores swelled; edges frayed. Pilum shafts, built to bend on impact, picked up water weight and became harder to throw cleanly in cramped woodland alleys. Pack animals slipped, dumping sacks that burst and scattered rations. Commanders tried to close ranks, but every halt caused a concertina of collisions down the line. Messages could not run faster than the rain. By the time orders arrived, the situation that prompted them had already changed.

Meanwhile the coalition spent its energy wisely. Short dashes out of cover, a flurry of missiles, a fast pullback; repeat a hundred times. The forest hid formations better than any palisade. When the sky eased they harried to prevent rest; when the rain thickened they let nature grind the Romans further down. In that rhythm — the weather’s beat, the ambushers’ timing — the battle took shape over days, not minutes. The legions still built fortified night camps, because habit and doctrine demanded it, but each morning they started worse off than the day before: fewer mules, less food, more wounded, and men who had slept in damp wool with nerves stretched thin.

Choosing the killing ground

Ambushes don’t happen anywhere; they happen in places that guarantee confusion for the enemy and safety for the striker. The coalition’s choke-point balanced two assets: natural mire and man-made bank. To one side lay ground that swallowed sandals; to the other rose a low slope where a rough wall had been thrown up from cut turf and packed sand. That wall didn’t need to stop a charge; it needed only to break lines and give cover for a rain of spears. With a narrow track between, the Romans could neither wheel left without drowning in mud nor wheel right without climbing into missiles. The weather made that geometry even crueller. Wet sod crumbles under feet; blown branches fall without warning. Every step asked for balance and attention better spent elsewhere.

Command decisions under a hostile sky

Varus was no fool, but the pressure of the season and scattered unrest pushed him into a false choice: move fast in bad conditions or lose the campaigning window entirely. He picked speed and paid the price. Once the storm broke and the column elongated, the right defensive move — form a solid block and force a way back to secure ground — became harder each hour. Instead the army tried to keep going, burning wagons that could not be dragged, ditching loads, and hoping the weather would turn. The coalition made sure hope never hardened into momentum. Every time a cohort found order, a fresh squall, a fresh feint, or a fresh shower of missiles broke it again.

On the third day, matters turned decisive. Attempting to force past the earthen wall and out of the killing corridor, the Romans slammed into repeated rushes by fighters who knew the tree lines and shallow ditches by heart. Rain masked movement; wet leaf litter muffled feet. The moment the legionaries tried to climb, they took missiles in the face and chest. The moment they held, the press came from both flanks. A tight shield wall can live in the open; in a hedge-choked lane with bog sucking at the left boot and a bank on the right, it can only wait to be cut. Leaders fell; files drifted; gaps opened; the body of the army came apart into clots of resistance. By evening the line had lost its spine.

Morale, fatigue, and the slow crash

Contrary to the way movies show it, Teutoburg was not a single mad rush. It was a slow crash in dreadful weather. The last good choices disappeared with the sun on day one. After that, every attempt to restore order cost blood. Every drop of rain thinned discipline a little more. That is why weather deserves to be called a weapon here: it punished the Roman way of war faster than it punished the Germanic way. The coalition did not need to sustain a shield wall across open ground; it needed only to sustain pressure. Wind and rain carried part of that load.

There’s also a psychological edge. In foul conditions, men look down: at their footing, at the drip from the shield rim, at the steam from wet cloaks. Heads-down marching kills situational awareness. Ambushers, dry under boughs, choose when to reveal themselves. Surprise is easier to achieve, panic easier to spark. A few sudden attacks at the column’s rear make the middle want to hurry; a shout at the vanguard makes it want to slow. Soon nobody trusts the pace they are forced to keep. That is how long columns disintegrate — not from a single blow but from a hundred small ones the weather amplifies.

Field craft versus field manuals

Roman doctrine excelled at turning open ground into a geometry of advantage. Build a camp; send out feelers; fix the enemy; press. The coalition inverted the board. They denied open ground, flooded the feelers with noise, refused to be fixed, and pressed only when the weather weakened the other side’s formations. Field craft beat the field manual. Cutting a slot through wet forest is engineering; keeping units alert while drenched is leadership; reading the sky and the ground together is a hunter’s art. The coalition had more of the last than the Romans did that week, and the last is what mattered most.

Lives, objects, landscape

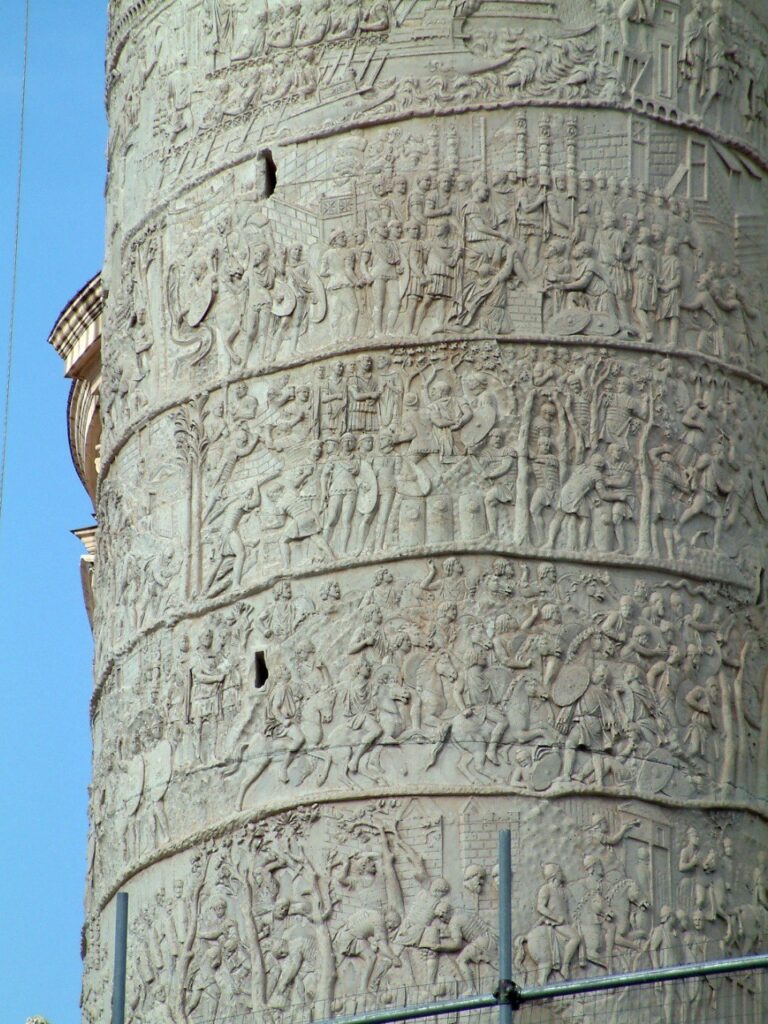

The battle’s archaeology tells a quiet story of exhaustion and loss. Coins from a legionary payday spill in little trails that trace panic. Fragments of armour turn up far from where they were issued. Buckles, sandal hobnails, and snapped javelin heads rest where men last ran or stood. The finds cluster along the corridor and at points where a rearguard must have tried to hold, then failed. In museum cases they look clean; in the ground they were simply the punctuation marks of lives interrupted.

Weather writes itself into the record too. Pits with mixed bones suggest hurried clearances after bodies had already lain in damp soil. Ironwork shows the sort of corrosion that comes with long contact with wet ground. The rampart’s layers — the blocks of cut turf, the sand, the way the bank slumped — match what you would expect from quick work in sodden conditions. None of this is proof in isolation; together, it is a chorus singing one theme: a fight stretched over wet days in a trap optimised by mud and wind.

Memory under changing skies

Teutoburg’s afterlife has had as many weather fronts as the battle itself. For centuries, the story lived in a handful of texts and a fog of guesses about place. In the last few decades, careful survey and excavation have made the battlefield legible in a way earlier generations could not have imagined. Even so, scholars continue to argue over details — exact routes, which bank of a ditch a unit used, how much the rampart owes to Germanic hands or Roman ones. That debate is healthy. What stays constant is the battle’s character: a trained imperial force unmade by a landscape that, under storm, turned hostile faster than Roman methods could tame it.

Could the Romans have beaten the weather?

It’s tempting to insist that better scouting or a tighter order of march would have saved the day. Perhaps. A more cautious route, fewer wagons, and a refusal to trust local guides would all have helped. So would a hard decision to stop and build a stout camp as soon as the first squall hit, then clear and fortify a return path. Yet doctrine, habit, and pride steer choices even when logic whispers otherwise. The culture of Roman campaigning assumed that discipline could master terrain. Most times it could. In this forest, in that weather, it could not — not in the time available, not with a column already stretched, not against an enemy who understood that the sky itself could be coaxed to fight on their side.

Weather tactics you can read in the sources

Ancient writers are usually more interested in heroics than in logistics, but even they notice weather when it turns battles. In their pages you catch the same details soldiers mutter today: branches breaking under gusts, mud turning paths to slides, signals lost in wind, rain driving into eyes that need to watch footing. No single line says “the coalition used weather tactically” because nobody in that world needed it spelled out. Of course they did. To pick the week, to pick the ground, and to pick the moment is to recruit the weather. That was the coalition’s quiet genius.

What the battlefield teaches

Modern visitors can walk the corridor, look over the reconstructed bank, and squint into the trees trying to imagine the noise. It helps to carry three thoughts. First, how fast order evaporates when a system designed for open ground is squeezed, soaked, and battered by wind. Second, how little force it takes to tip units from control into flight when that squeeze lasts for hours. And third, how effective a light, locally supplied, weather-hardened force can be when it refuses to give the set-piece battle its enemy hopes for.

Weather is not magic. It is a multiplier. Teutoburg’s lesson is not that storms decide everything; it is that armies who understand what storms do to humans, animals, and wood and iron can make them do half the work. Arminius and his allies did not invent ambush; they chose the week that made it irresistible. The rest followed: marooned cohorts, drowned signals, exhausted men, and, at last, a Roman commander who chose death over capture as his broken army folded into the wet trees.

Aftermath: when the weather clears

Rome learned from the loss. Later expeditions came leaner, with a sharper eye for how quickly German forests can strip an army of poise. They moved when ground and sky allowed, and they fought to recover the lost eagles rather than to refound the province. Strategically, the Rhine became the practical frontier. You can draw that line on a map, but it is also a line drawn by rain clouds and westerly winds: the point at which Rome decided that the cost of mastering that weathered landscape was higher than the prize.

Stand under the trees today and you still feel how the place tells armies what to do. The trunks come close; paths tilt; low ground gleams darker than it should. Add rain and a headwind and you can hear, if only faintly, why an empire famous for roads and order lost all sense of both on a few bad days in a forest that refuses to be neat. Weather won’t swing a sword for you. But if you time your step to the storm, it will clear your way.