Rome in the middle of the first century BC stood at a crossroads. Economic anxiety, military demobilisation, and partisan street violence forced citizens to look increasingly toward single personalities rather than the collective wisdom of the Senate. Literacy among urban plebeians was rising, cheap papyrus from Egypt had begun to flow into the capital, and public noticeboards carried daily political gossip. In that setting Gaius Julius Caesar realised that perception could decide elections and even wars. A statesman who controlled headlines, monuments, and money itself would gain an edge unavailable to earlier generations.

Formative Years: Advocacy, Debts, and Name Recognition

Caesar’s aunt was married to Marius, hero of the Cimbric War; his wife Cornelia belonged to the radical Cornelii Cinnae. Sulla’s dictatorship stripped young Caesar of the priesthood and brought early exile, yet that setback taught a lesson: public memory can be re‑engineered. After Sulla’s death, Caesar prosecuted provincial governors notorious for extortion, funding each case with money borrowed at ruinous interest from Marcus Licinius Crassus. Verdicts were less important than appearances. Jurors sat in open‑air courts on the Forum, surrounded by spectators; each dramatic cross‑examination pushed the name “Caesar” into the Acta Diurna and private letter collections. Within a decade he was pontifex maximus, largely on the strength of visibility rather than seniority.

Political Branding through Partnerships and Spectacle

The so‑called First Triumvirate (59 BC) united Caesar with Crassus and Pompey. Their pact was informal yet carefully choreographed. Pompey married Caesar’s daughter Julia during a public ceremony on the steps of the Capitoline Hill; Crassus underwrote grain distributions timed with the vote on Caesar’s agrarian bill. A single week of largesse cost over 23 million sesterces, more than the annual income of many senatorial families, but the investment paid dividends at the ballot box. Contemporary pamphleteers noted that diners carried away ceramic bowls stamped with a tiny Venus, an early instance of mass‑produced campaign merchandise.

The Gaul Dispatches: Turning Battle Reports into Bestseller Prose

While governor of Cisalpine and Transalpine Gaul (58–50 BC) Caesar drafted periodic commentaries written in spare, vivid Latin: Commentarii de Bello Gallico.1 Couriers raced the manuscripts to Rome, where slaves read them aloud in taverns and baths. The prose framed tribal coalitions as existential threats and justified extraordinary expenditure of Roman blood and treasure. By referring to himself in the third person (“Caesar sends the cavalry”), the author gained an air of objectivity. Later critics, from the scholar Mommsen to modern military historians, classify the work as strategic public relations; it granted voters a sense of shared victory precisely while safeguarding the commander’s personal authorship of success.

Numbers, Maps, and Selective Emphasis

Statistics inside the Commentarii served rhetorical goals. Enemy casualties dwarfed Roman losses in almost every episode. Geography placed battlefields near rivers that formed convenient natural frontiers, persuading readers that conquest secured Rome’s safety lines. Opponents were labeled barbari, suggesting chaos and unpredictability, whereas auxiliary leaders loyal to Caesar were praised as “wise” or “steadfast.” In short, language did the work of a modern infographic.

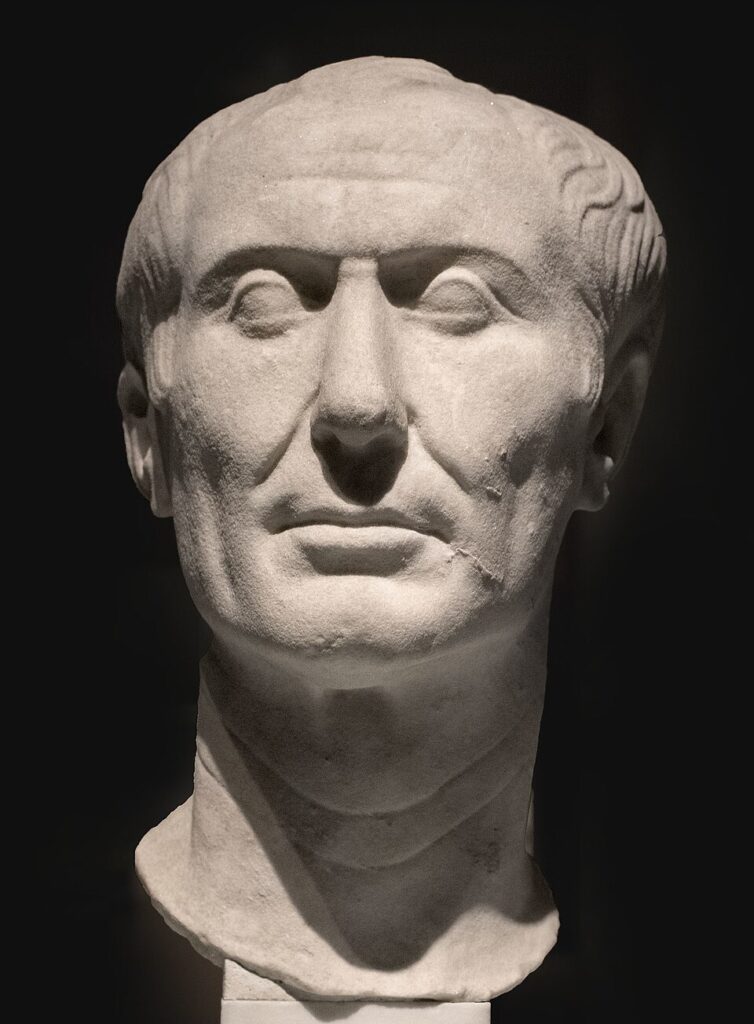

Money Talks: The Portrait Denarius of 44 BC

The most audacious propaganda piece was small enough to fit in a purse. Early in 44 BC Caesar authorised striking silver denarii bearing his own likeness crowned with laurel, flanked by the legend DICT PERPETVO (“dictator for life”).2 Roman custom had reserved living portraits on coinage for monarchs in Hellenistic kingdoms; by breaking that taboo Caesar signalled a new political reality. Numismatists estimate that millions of examples left the mint in fewer than eight weeks, supplying legion payrolls in Spain, Macedonia, and Syria. Each coin passed from legionary to innkeeper to farmer, a metal document that never needed official couriers.

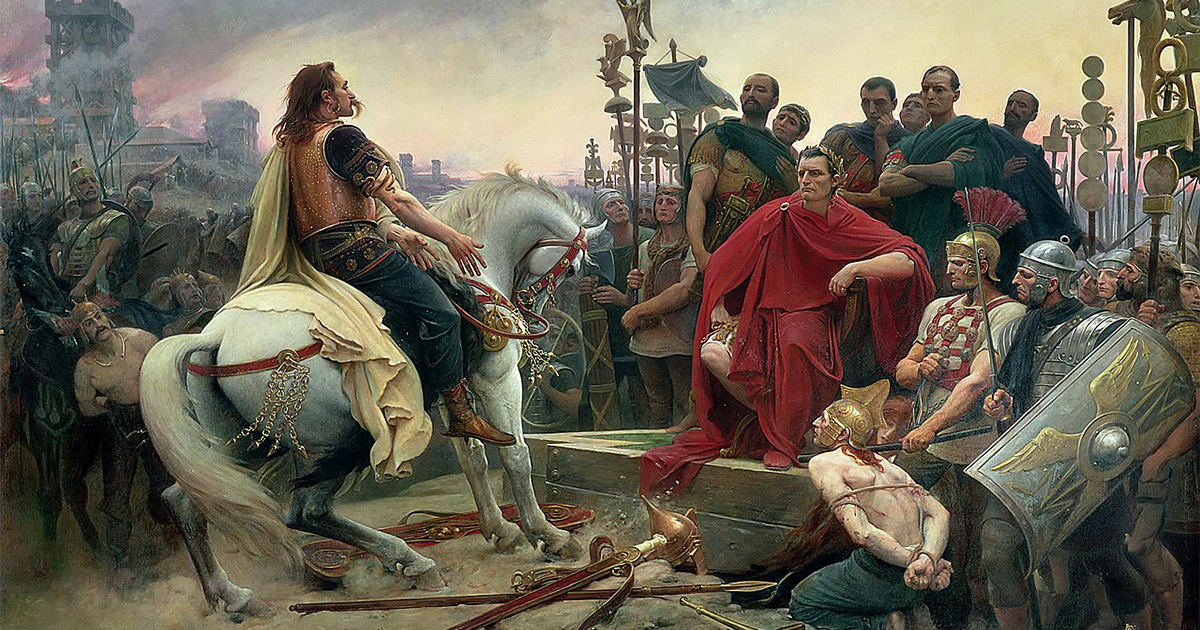

The Quadruple Triumph of 46 BC

Upon defeating Pharnaces, Juba I, and the Pompeian remnant, Caesar staged four triumphs in one thirty‑day span.3 Cassius Dio lists Pompey’s battered arms, Gallic chariots, and full‑scale river dioramas paraded past the Temple of Saturn. Exotic wildlife stunned the crowds. A giraffe—the first recorded in Europe—walked the Circus Maximus, rolled out of a specially constructed barge and escorted by Nubian handlers.4 Such prodigies reinforced the image of Rome as a city that could command the ends of the earth, and Caesar as the linchpin holding its compass steady.

Architecture: Stone as Story

Money from Gaul financed marble. The Forum Iulium, begun in 54 BC, offered traders a new colonnade while leading every visitor’s gaze toward a high‑altar statue of Venus Genetrix. Adjacent rose the Curia Julia, wider than the old Curia Hostilia and aligned on an axis that highlighted Caesar’s family rostra.5 Senators entering the chamber confronted carved reliefs of Aeneas carrying Anchises, underlining Julian descent from the Trojan hero. Political messaging became part of the cityscape; to do business meant walking literal corridors of dynastic narrative.

Temple of Venus Genetrix: Mythology Meets Statecraft

Dedicated on 26 September 46 BC—the final day of the African triumph—the Temple of Venus Genetrix fused private genealogy and civic cult.6 Ovid later described a colossal ivory statue inside, clutching an apple and helm. Reliefs depicted Paris awarding the apple to Venus, a scene linking the goddess’s beauty with political judgment. Festivals at the site became annual reminders that Caesar’s bloodline, by his telling, flowed from divinity. The message proved durable: Augustus retained the priesthood and incorporated Venus’s star into legionary standards.

Clementia Caesaris: Mercy as a Weapon

After Pharsalus, Pompey’s lieutenants expected confiscations and executions. Instead, Caesar invited many to dine. By publicising letters of thanks from Marcus Junius Brutus and even from Cicero, he transformed personal leniency into a civic virtue.7 Roman writers noted that mercy (clementia) was traditionally a prerogative of the populus; Caesar appropriated that privilege, reinforcing one‑man rule under the guise of benevolence.

The Acta Diurna and Bulletin Control

Caesar did not invent the daily notice sheet, yet he formalised it. Beginning in 59 BC clerks posted summaries of senatorial debates, new laws, gladiatorial schedules, and celestial omens on whitened boards in the Forum.8 Under Caesar, military dispatches joined the roster, giving frontline propaganda the same civic legitimacy as marriage announcements. Merchants visiting from Palermo could read Gaulish victory headlines before they heard them from bards or returning soldiers, guaranteeing that the dictator’s version of events framed every subsequent conversation.

Crossing the Rubicon: Narrative Supremacy during Civil War

In January 49 BC, Caesar stepped over the Rubicon with one legion. He sent ahead proclamations declaring that the Senate’s tribunes had been threatened and that he marched to restore lawful order. Copies flooded Etruscan hill towns and Adriatic port cities. Pompey’s camp responded days behind, forever playing narrative catch‑up. Within three months Spain surrendered; Caesar credited the swift victory to local enthusiasm rather than legionary speed, again shaping history in real time.

The Assassination and the Story that Refused to Die

Ides of March, 44 BC: conspirators struck inside the Theatre of Pompey. Yet their target’s communication network kept breathing. Mark Antony displayed the blood‑clotted toga on the Rostra, reciting the dead man’s will bequeathing gardens to the urban plebs. Rumours flew that Brutus had been spared once before by Caesar’s mercy, darkening his deed with ingratitude. The Senate hurried to outlaw nomen tyrannicidum graffiti, but copies of the will already seeded fury in Subura taverns. Augustus later mined the backlog of imagery—laurel coins, Venus starbursts, even the Julian calendar reform—to claim he was finishing rather than overturning his adoptive father’s programme.

A Template for Future Regimes

From Napoleon’s bulletins after Marengo to modern social‑media photo ops, heads of state still borrow Caesar’s triad: control the message, repeat the symbol, reward the crowd. His skill lay not merely in waging war but in ensuring that every senator, legionary, and freedwoman awoke each morning inside a story that cast the Julian household as Rome’s natural pilot. The Republic fell, yet the propaganda blueprint endured, adaptable to emperors, popes, and presidents who understood that power, once seen, is half possessed.

References

- Aspects of propaganda in the De Bello Gallico, ResearchGate paper by A. Spilsbury (2015).

- “Julius Caesar’s Propaganda: The First Roman Coins Featuring the Ruler’s Portrait,” Short History (2023).

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.14–24 (Loeb Edition).

- “When Julius Caesar Brought the First Giraffe to Europe,” The Vintage News (2017).

- N. McFadden, “Memory, Propaganda, and the Roman Senate House,” University of Iowa thesis (2019).{index=4}

- “Temple of Venus Genetrix,” Encyclopaedia Romana entry.

- Vaznetti, “Caesar’s Clementia,” LiveJournal essay (2005).

- Acta Diurna, Wikipedia article (updated 2025).