On a small island in the far Pacific, a handful of wooden boards still refuses to give up its words. The script is called rongorongo, and for a century and a half people have tried to read it. Some claimed victory, others promised a breakthrough, a few announced full decipherments that later collapsed. Today, the tablets are as eloquent as ever, yet the message remains out of reach. This is not for lack of effort. It is because the conditions needed to crack a script—context, quantity, and comparison—were largely stripped away before scholars arrived.

What follows is the story of how those attempts faltered, and why the tablets keep their silence. Along the way we will look closely at the objects themselves, the reading order, the famous “calendar” passage, the hopeful claims, and the sober reasons they did not hold. It is, in short, a case study in why some scripts yield and others do not.

What rongorongo is (and what it might not be)

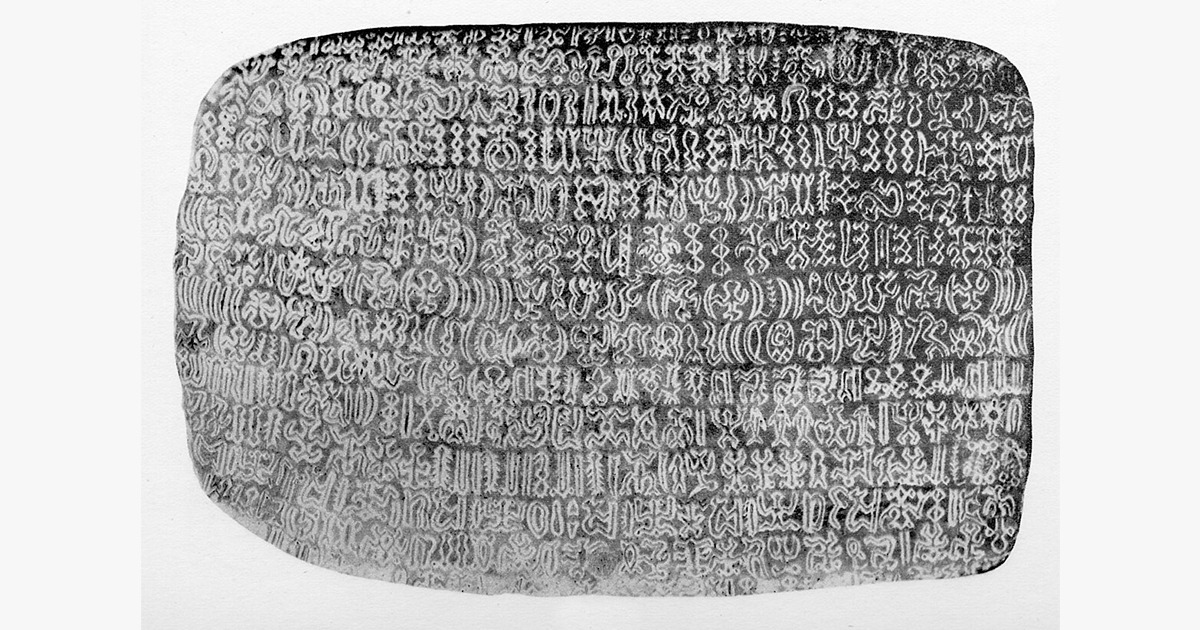

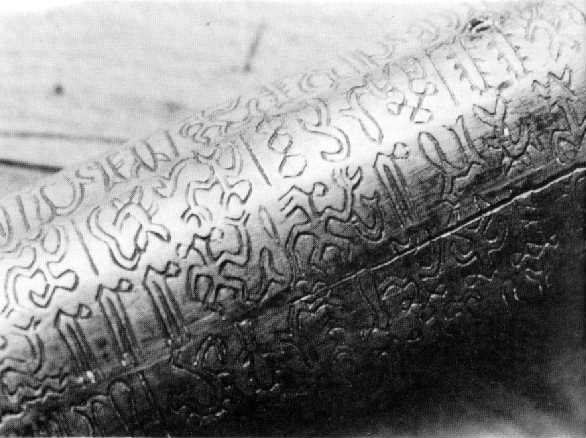

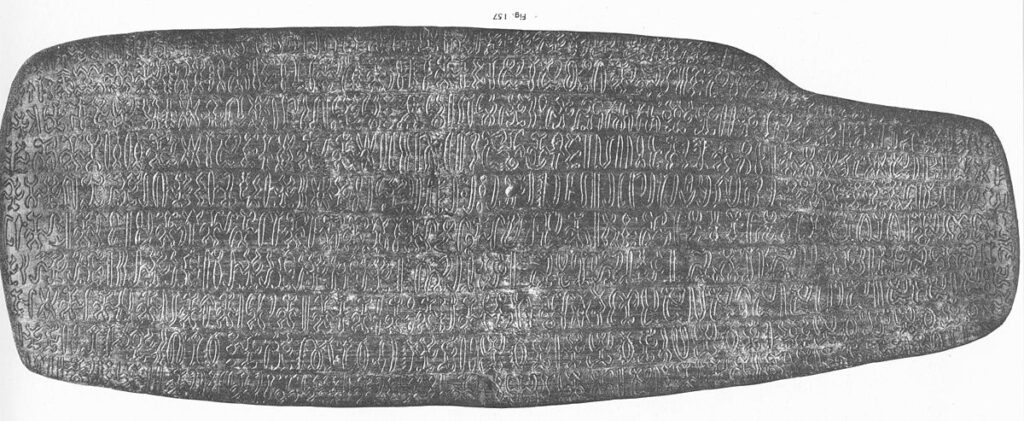

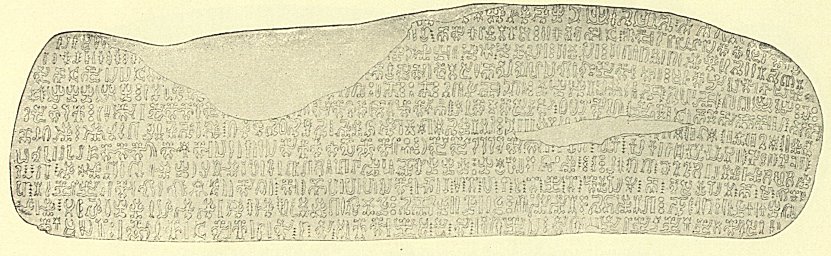

Rongorongo survives on a small corpus of wooden objects—mostly tablets, plus a staff, a reimiro chest ornament, and a few other pieces—inscribed with rows of tiny human, animal, plant, and abstract signs. The number of authentic inscriptions is commonly given as about twenty-six, scattered today in museums from Rome to Santiago and Berlin. That is a library so thin that every line matters. The script’s status is debated: some hold it to be true writing for Old Rapanui; others call it a mnemonic device for chants. Either way, it is a sophisticated system with strict order and excellent craftwork.

The carving is precise. Scribes incised the signs with great control and very few mistakes. They wrote in a distinctive pattern called reverse boustrophedon: the first line runs leftward; the next runs rightward with the glyphs turned 180 degrees; then left again, and so on. If you rotate the tablet at the end of each line, the text always reads left-to-right. That pattern is one of the few things everyone agrees on.

Discovery and loss, almost at the same time

The first outsider to note the inscribed tablets was the missionary Eugène Eyraud in 1864. Within just a few years, Bishop Tepāno Jaussen of Tahiti began collecting the boards as scientific curiosities, spurred by reports that such writing existed on Rapa Nui. During that same decade, the island suffered catastrophic raids by Peruvian slavers and the ravages of introduced disease. Communities were emptied, elders were lost, and with them, knowledge that had passed by memory. By the time the tablets reached museums, context was fractured and the reading tradition—if one still lived—had no safe ground on which to stand.

That is the first failure condition. Decipherment thrives on living memory, bilingual labels, or robust local explanations. Rapa Nui was denied those supports at the critical moment. What remained were remarkable objects, thin documentation, and stories that did not always agree.

The tablets themselves: what they show clearly

Each board is unique, yet several features repeat. Surfaces are planed and sometimes fluted. The signs, often a few millimetres high, sit in regular rows. On tablets such as the Mamari board and the two “Santiago” tablets, the carving is tight and consistent across long passages. Elsewhere, a staff carries lines that wind around the shaft, forcing the carver to adjust spacing and stroke. The visual discipline is striking. It suggests trained hands and standard habits down to the sequence of strokes within a single glyph.

These physical clues prove a system, not a casual scratch. But a system can encode many things: full language, numbers, names and titles, ritual prompts. The challenge is deciding which.

How people tried to read them

Jaussen hoped to recover the key by asking an islander in Tahiti, Metoro Tau‘a Ure, to “read” the boards aloud. He dutifully recorded what Metoro chanted. The results—highly variable, often Tahitian rather than Rapanui, and mainly descriptions of what a glyph might depict—have long been judged unreliable for phonetic reading. They look less like text and more like free association or ritual gloss. As a guide to language values, they do not hold. As a glimpse of how someone might talk around the boards in the late nineteenth century, they are fascinating but inconclusive.

Later, scholars turned to comparison. The most influential framework came in 1958 from Thomas Barthel, who catalogued hundreds of sign types and assigned each a code. His sign list remains the reference. Statistical work since then suggests that many of those hundreds are variants and ligatures; counts in the range of a hundred-plus core signs are often cited. That is a plausible inventory for a logo-syllabic system, or for a compact set of mnemonic cues. Unfortunately, counts do not choose between those options on their own.

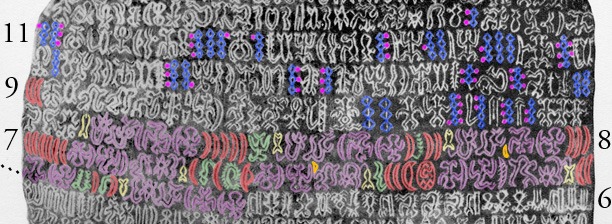

The famous “calendar”—and its limits

One passage is widely accepted as calendrical: a series on the Mamari tablet that maps a cycle of nights consistent with a lunar month. The sequence aligns with astronomical expectation and with Polynesian calendrical practice. It is the best-grounded match between a rongorongo text and a specific referent. Yet even here, we do not read the words; we identify the structure. The rest of the corpus has not yielded equivalently secure anchors, and without anchors, letters and sounds have nowhere to settle.

High hopes and bold claims

Across the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, several researchers announced partial or full solutions. Some saw genealogies and ritual pairings in repetitive strings. Others proposed number words, phonetic complements, even entire reading algorithms. A few monographs attracted press, then met sustained criticism. The pattern is familiar from other undeciphered scripts: enthusiastic pattern-finding followed by sober counter-examples, with no consensus at the end.

What usually goes wrong? Proposals succeed on a few short lines and fail elsewhere. A value that fits here breaks the distribution there. A sign supposed to function as a phonetic element refuses to behave consistently in new contexts. Or the reading requires so much latitude—homophones on demand, wild polysemy, free alternations—that falsification becomes impossible. When a theory can always rescue itself, it has left the terrain of decipherment.

Why attempts keep failing: the nuts and bolts

1) The corpus is too small and too damaged. The surviving texts number only in the twenties. Several are fragmentary or badly worn. For a full phonetic decipherment, that is simply not enough material. Even Linear B needed hundreds of tablets and a lucky structural hunch to give way.

2) There is no bilingual, no long plain-text context. Rosetta-style helps are absent. We do not have a tablet beside a translation, nor a list of month-names beside festival scenes. Without such anchors, values drift.

3) Provenance is patchy. Many boards were collected after the reading tradition was broken, often with scant excavation records. We cannot place most tablets in precise ritual, social, or geographic contexts. Decipherment loves context; rongorongo lost it.

4) The sign inventory is tricky. Barthel’s list tallied ~600 signs, but many are variants. Narrower counts around a hundred-plus core types are plausible. That range could fit a syllabary, or a constrained set of logograms, or a mnemonic system. Statistics alone cannot decide, and mixed systems blur categories further.

5) The subject matter may be specialised. If the boards cue ritual recitations, lists of offerings, or initiatory names, their vocabulary will be narrow and repetitive. That is the worst case for decipherment: few topics, heavy formulae, and many proper names. You can fit multiple readings to such data without contradiction.

6) Late copies confuse the timeline. Radiocarbon dates on some pieces fall in the nineteenth century; at least one tablet has yielded a fifteenth-century date, suggesting deeper roots. A mixed horizon means scribal traditions may have changed—materials, conventions, even purposes—making the small corpus internally uneven.

Reading order and layout: one clear win

Although sound values remain elusive, layout is secure. The reverse boustrophedon format is not guesswork; it is obvious from the carving. So is line order: many tablets begin at a corner with neat margins, and the surface wear supports a standard sequence of handling. Scribal quality is high, with remarkably few corrections. This tells us that scribes followed well-learned patterns and copied with confidence. Unfortunately, perfect penmanship does not equal an alphabet key.

What modern imaging and new dates add

Recent documentation campaigns have produced photogrammetric models and high-resolution images of crucial tablets, improving readings of faint strokes and expanding sign counts on specific pieces. A tranche of radiocarbon tests has also complicated, and possibly enriched, the timeline. Some tablets cluster in the 1800s; at least one piece strongly indicates pre-European centuries. If authenticated across more objects, that suggests a tradition older than missionary contact, even if its late use was already rare or restricted. It supports neither easy “post-contact invention” dismissals nor any quick phonetic mapping. It does, however, justify continued, careful work.

The “why it mattered” question

Even without a reading, the script matters for cultural history. Rapa Nui produced a formal, island-wide system of incised signs used on valuable objects, with disciplined layout and trained scribes. That alone is extraordinary for a small, remote community. Whether the system mapped language line-by-line or cued specialised recitations, it encoded and protected knowledge. It also bound identity to material culture in a way that survived catastrophe. The tablets reached us because people valued them even when their words were fading.

Could a breakthrough still come?

It is not impossible, but any success will almost certainly be partial and incremental. Three paths look promising: first, exhaustive, transparent documentation of every stroke on every authentic object; second, careful statistical modelling that respects scribal variation and tests hypotheses across the whole corpus; third, deepening ethnographic and linguistic work with Rapanui oral traditions and Old Rapanui language, to tighten plausible semantic domains. A dramatic “aha” moment is unlikely. A slow drift from mystery to constrained understanding is not.

How to look at a tablet and see more

Stand before a good photograph and trace the rows with your finger. Watch the line flip and your brain flip with it. Notice how certain signs repeat in clusters, and how others serve as separators. Look for small corrections—rare but telling—that show a scribe catching an error. Then step back and imagine the board in a house or at a ceremony, handled carefully, perhaps chanted in company. That, at least, is something we can say with confidence: these boards were made to be seen and used, not simply hoarded.

Lessons from a failed decipherment

Rongorongo is not a failure; decipherment attempts are. The boards remind us that writing systems are not puzzles made for us. They are tools embedded in particular lives. When violence, disease, and removal smash the surrounding world, the tool may survive but the instructions do not. Scholars inherit beautiful fragments and do the best they can. Sometimes “the best” is an honest admission: here is structure, here are numbers, here is a likely calendar, and beyond that, we will not pretend to more than we know.

Why the tablets still move people

Because they do what portraits do: they place us near another mind. Not with a face this time, but with the evidence of deliberate marks laid in sequence by trained hands. Every line says, this mattered. In a museum case or an online image, you can feel that urgency. Even if the words never come back, the care is legible.

In short

The decipherment of rongorongo has not failed from lack of imagination. It has failed because the tablets reached us almost naked of context, few in number, and cut off from a reading tradition already collapsing under outside pressures. We have a likely lunar passage, clear layout rules, improving documentation, and mixed but intriguing dates. We do not have the bilinguals, the bulk, or the continuity that give other scripts a fighting chance. That is a hard truth, but a useful one. It tells us where to spend our energy: on patient documentation, respectful collaboration with Rapanui knowledge holders, and careful, falsifiable proposals that touch the whole corpus rather than a single tempting line.