Comparative mythology: Greek, Roman, Norse, Egyptian is a practical way to read four influential traditions side by side without flattening their differences. The aim is simple. See how each culture explains the world, power, fate, justice, and death. Then note where stories truly align and where they only look similar from far away. You end up with a map that respects context and still lets you trace recurring patterns across time.

This guide balances clarity with care. It shows workable parallels and also flags common traps. It speaks plainly about sources, dates, and what we can and cannot know. Most of all, it keeps the focus on why these stories lasted: they answer needs that people keep having, whether in an Egyptian delta town, a Greek island port, a Roman colony, or a Norse farm on the edge of the sea.

How to compare myths responsibly

Comparison works only when you hold two ideas at once. Human needs repeat. Cultures differ. So we look for patterns without forcing matches. We check the age and type of each source. We watch for later edits, translation choices, and religious politics that colour the telling. And we admit uncertainty when the evidence is thin. Good comparison is a discipline, not a shortcut.

Sources at a glance

- Greek: Homer, Hesiod, lyric poets, tragedians, historians, inscriptions, vase painting, sculpture, cult calendars.

- Roman: Latin poetry and prose (Ovid, Virgil, Livy), state religion, inscriptions, imperial cult, household shrines.

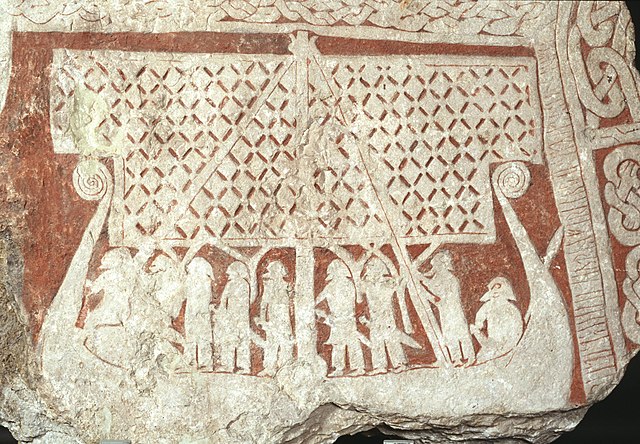

- Norse: Poetic and Prose Edda, skaldic verse, sagas, law codes, picture stones, runic inscriptions, post-conversion manuscripts.

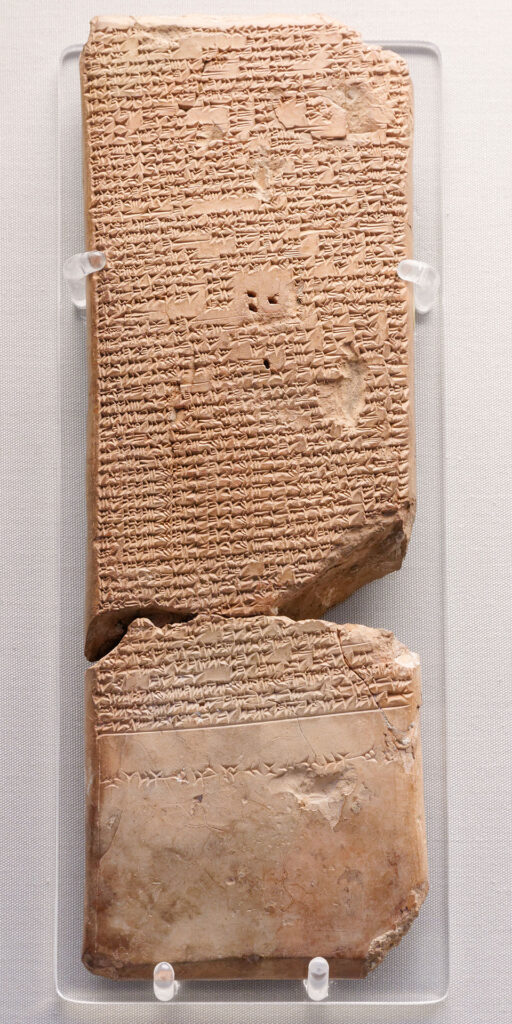

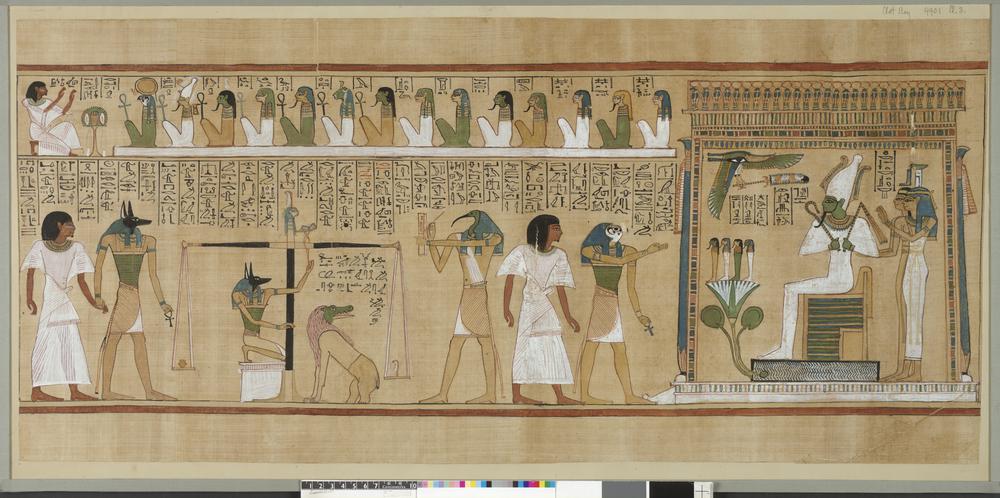

- Egyptian: Pyramid and Coffin Texts, Book of the Dead vignettes, temple inscriptions, ritual papyri, tomb art.

Dates matter. Greek epic coalesces in the first millennium BCE. Roman state religion evolves under the Republic and Empire. Norse myth is written down after Christianisation, so it is filtered through later pens. Egyptian material spans three millennia with regional styles. Keep that in mind whenever two myths look “the same”. Often they are cousins, not twins.

Making the world: four cosmologies

Creation begins with chaos or water in many traditions. The details, however, do real work. They tell you what a culture fears and what it trusts.

Primordial beginnings

- Greek: Hesiod opens with Chaos, then Gaia, Tartarus, Eros. Form arises as powers take shape. The cosmos is layered and familial.

- Roman: Often borrows Greek structures, but history and law pull into focus. Order is a civic virtue, not just a cosmic one.

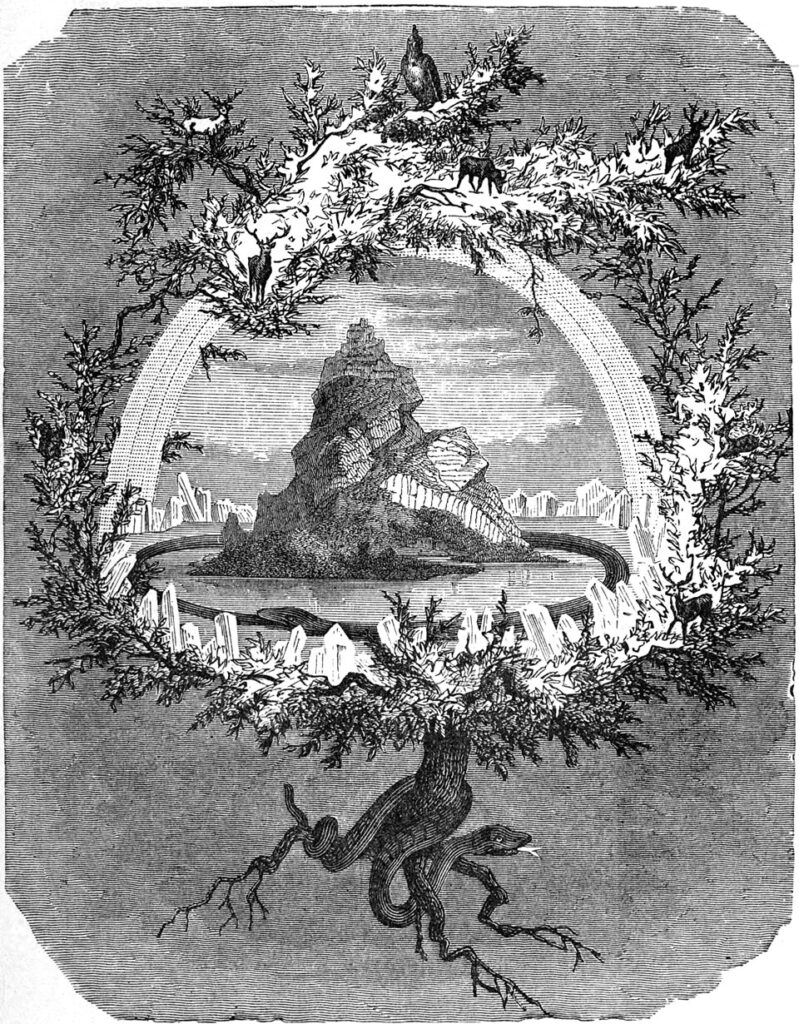

- Norse: Ginnungagap lies between fire and ice. From this tension the first beings emerge. The world is a build in hostile weather.

- Egyptian: The primeval flood (Nun) yields a mound. The sun god rises. Creation is daily, rhythmic, and tied to the river’s pulse.

Read these carefully. Greece personifies forces and makes drama. Rome frames order and duty. Norse myth imagines risk and craft. Egypt sets creation on a schedule and makes maintenance a sacred task. Every later story follows from that first move.

Who rules and how

Pantheons are not just family trees. They are arguments about power. Who decides. Who obeys. Who pays when balance fails.

Greek and Roman peaks

Greek myth centres on Zeus, who rules by treaty after a generational war. Justice is personal and often negotiated. The Roman Jupiter inherits Zeus’s sky and thunder yet feels more administrative. Law and pact are explicit. You sense the Senate even on Olympus. Roman religion is public, calendrical, and civic. Greek religion mixes polis cults with wild mountains and private initiations.

Norse balance of chiefs and fates

Odin rules through knowledge, sacrifice, and deals with powers older than himself. Thor keeps giants at bay with force that feels necessary rather than cruel. There is no eternal victory. Even the gods are mortal in the end. Leaders keep danger at the edge long enough for life to happen.

Egyptian poise

Egypt spreads power through a network. Ra sails, Osiris judges, Isis protects, Horus rules as king. The key term is Ma’at: truth, balance, right order. Pharaoh embodies Ma’at. Temples perform it. Myth and statecraft align so that the sun rises and the Nile floods. Stability is a daily achievement, not a lucky accident.

Fate, law, and the limits of choice

Every tradition places a limit somewhere. Call it Fate, Ma’at, or the Norns’ weaving. The name varies. The boundary does not.

- Greek: Moira sets terms even gods respect. Hubris brings ruin because it denies scale.

- Roman: Fatum folds into public duty. Stoic hues colour later readings. Virtue means living according to nature and office.

- Norse: The Norns weave past, present, future. Courage matters because outcomes cannot be avoided, only met well.

- Egyptian: Ma’at is the standard. Hearts are weighed. Choices have afterlife weight, literally.

These frameworks shape hero stories. Greeks learn to know their place and act well within it. Romans add duty to state and family. Norse heroes model steadiness in the face of loss. Egyptians take right action as a scale you will face later in a hall lit with truth.

The underworlds compared

Afterlife maps reveal a culture’s deepest anxieties and hopes. They also teach the living how to behave.

Greece and Rome

Hades/Pluto rules a realm with districts. Heroes visit and return. There are punishments, but most souls are quiet shades. Roman poets sharpen moral zones for rhetoric and drama. Mystery cults (Dionysus, Demeter, later Mithras and Isis) promise personal salvation or renewed life in symbolic form.

Norse

Death splits by manner and loyalty. Valhalla for chosen warriors. Fólkvangr with Freyja. Hel for many others. This is not simple reward and punishment. It is a sorting by role. The message is plain. Live in a way that helps your community endure.

Egypt

The Duat is a trial and a journey. Spells guide, names protect, and the heart must be light. If you pass, you live with the justified; if not, you cease. The emphasis is on balance rather than terror. Order is a blessing. You join it if you kept it while alive.

Heroes and the patterns they follow

Heroes show what a culture values under stress. They also reveal what it will forgive.

- Greek: Herakles performs labours that tame a wild world. Odysseus survives by wits. Perseus solves an impossible threat with gifts and nerve.

- Roman: Aeneas carries father and gods through fire, then builds a future. Obedience to destiny and care for family matter more than style.

- Norse: Sigurd wins treasure and tragedy. Beowulf (in a related tradition) kills monsters then dies for his people. Glory and cost are a pair.

- Egyptian: Horus wins kingship after legal and physical trials. The story values lawful succession and collective stability over individual flair.

If you compare these arcs, a shared thread appears. Power is legitimate when it protects a community. Trickery is acceptable if it restores balance. Breaking oaths shatters worlds. Gifts require repayment. The details move, the ethics stay recognisable.

Magic and ritual: different toolkits

Rituals make myth practical. They turn stories into habits that keep a city, a farm, or a ship afloat.

Greek

Public festivals, sacrifices, oracles, healing sanctuaries, and mystery rites form a busy calendar. Private life mirrors public cult. Oaths carry divine witnesses. The line between religion and everyday prudence is thin.

Roman

Priestly colleges, augurs, and household Lares anchor religion to law and schedule. Omens are not whims. They are procedures. Even foreign gods enter Rome by treaty. The result is a religious bureaucracy that feels surprisingly modern in its paperwork.

Norse

Blót feasts, oath rings, and seasonal rites create solidarity. Seiðr and runic magic sit at the margins yet matter in story logic. Women often lead or mediate ritual knowledge, which fits the high status of prophecy in these tales.

Egyptian

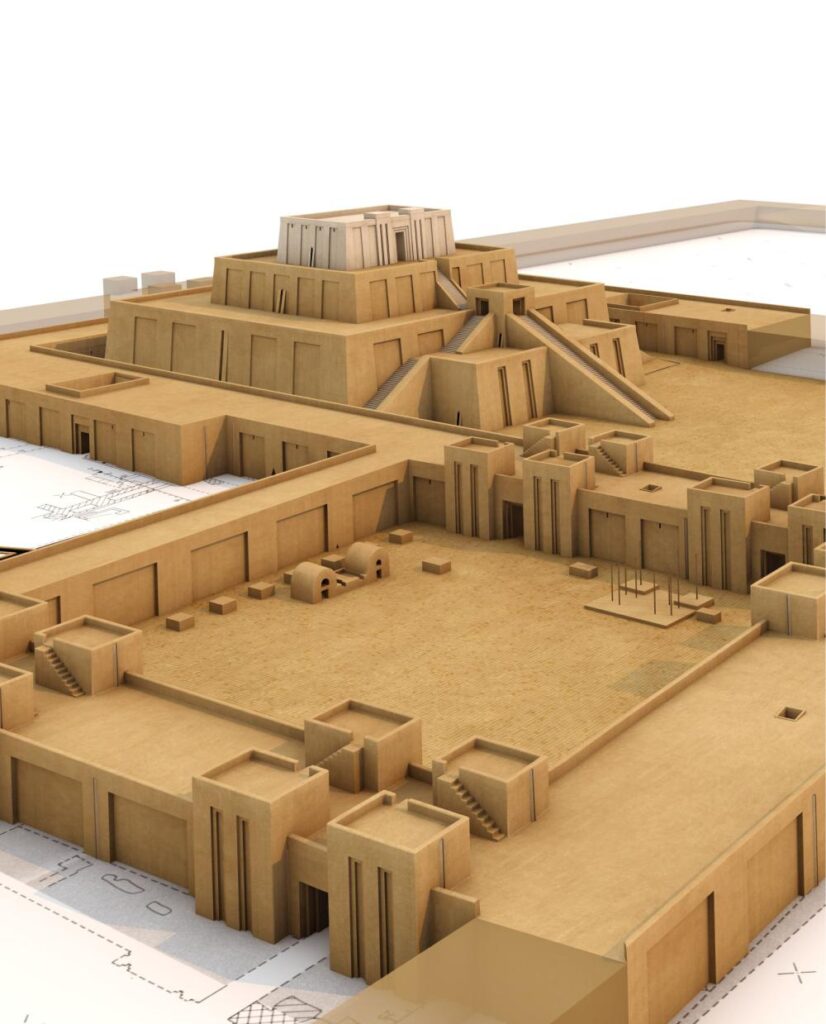

Temple liturgies daily enshrine the sun’s journey. Priests cleanse, awaken statues, and maintain cosmic order by precise action and recitation. Funerary rites secure the dead. The effect is cumulative: small faithful acts keep the world on time.

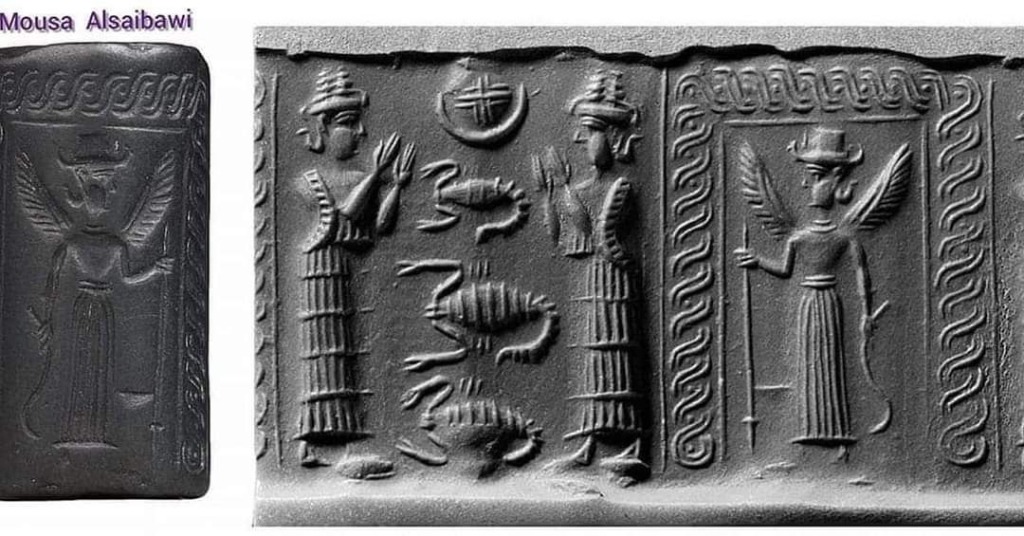

Animals, symbols, and what they signal

Animals and objects condense meaning. They also travel well. A thunder symbol works in mountains and on plains, whether it belongs to Zeus, Jupiter, or Thor. Yet context still rules.

- Greek/Roman: The thunderbolt and eagle signal sky rule. Olive and laurel bind victory to cultivation and learning.

- Norse: Hammer, ravens, wolves, and world-tree speak of force, memory, threat, and structure. Knotwork compresses cosmology into line.

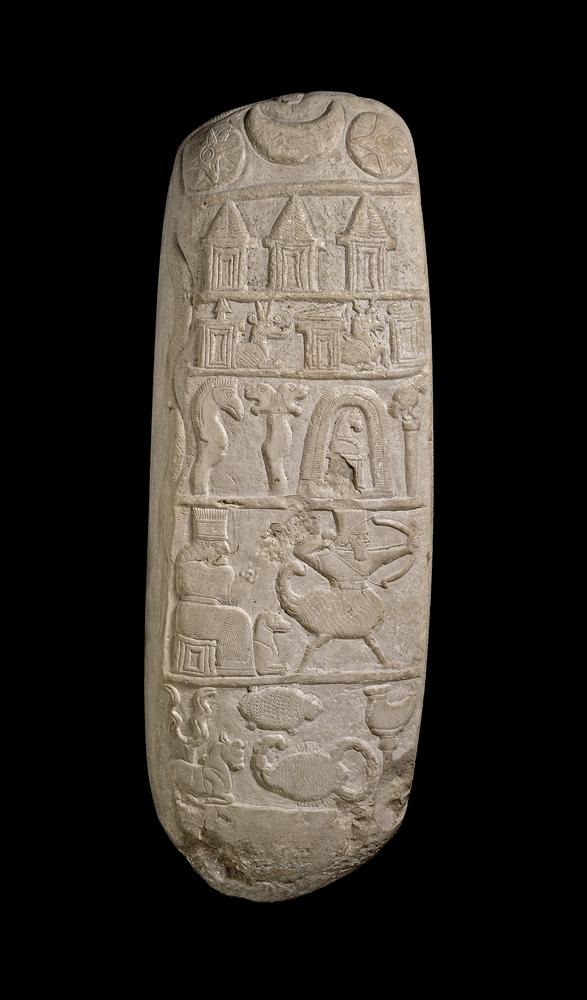

- Egyptian: Eye of Horus protects. Ankh gives life. Scarab renews. Solar disc crowns. Hieroglyphs themselves act as protective forms.

Symbols do politics quietly. When a city stamps a coin with a goddess, it declares allegiance as surely as a speech. When a household hangs a symbol over a door, it invites help and warns harm away.

Borrowing, blending, and resisting

Traditions talk to each other. Sometimes they blend; sometimes they fight. Either way, contact leaves marks.

Greek and Roman exchange

Romans often used interpretatio to identify Greek gods with Latin names. That exchange can mislead modern readers into thinking the systems are identical. They are not. Roman religion keeps a sharper civic edge, while Greek practice leaves more room for local, ecstatic, or initiatory forms. Still, poets from both cultures borrow freely. The result is a shared Mediterranean vocabulary of divinity with regional accents.

Greek and Egyptian meetings

After Alexander, the Ptolemies create Serapis, a composite deity with broad appeal. Isis cults spread across the Roman world. Ideas move both ways. Egyptian motifs refresh Greek and Roman art. Greek language shapes Egyptian writing for a time. The blend is creative rather than chaotic.

Norse in a Christian frame

Most Norse texts were written down after conversion, so Christian ethics brush the edges of older stories. That does not erase their voice. It does shift emphasis here and there. Good readers learn to hear the older melody through later harmony.

Women, power, and voice

Each tradition gives women space in different ways. Greek myth offers Athena’s mind, Artemis’s independence, Hera’s rank, and Aphrodite’s dangerous grace. Roman stories praise duty and household strength. Norse tales show seeresses and queens steering outcomes with word and rite. Egyptian myth places Isis at the centre of succession, magic, and maternal power.

None of these are modern ideals. They still speak. They show how cultures negotiate care, courage, law, sex, and speech. They also remind us to read specific women, not generic categories.

What survives in language and habit

Echoes remain in weekdays, festivals, metaphors, and place-names. We still call difficult choices “labours”. We still meet people named for gods. We still hang symbols near front doors. You do not need to believe a myth to live in its shade.

Reading well: a brief method

- Start with the source. Who wrote it, when, for whom, and why.

- Look for structure before detail. What problem does the story solve.

- Map power. Who gets to speak, decide, punish, forgive.

- Watch for ritual echoes. What actions turn belief into practice.

- Compare carefully. Note real parallels and honest gaps.

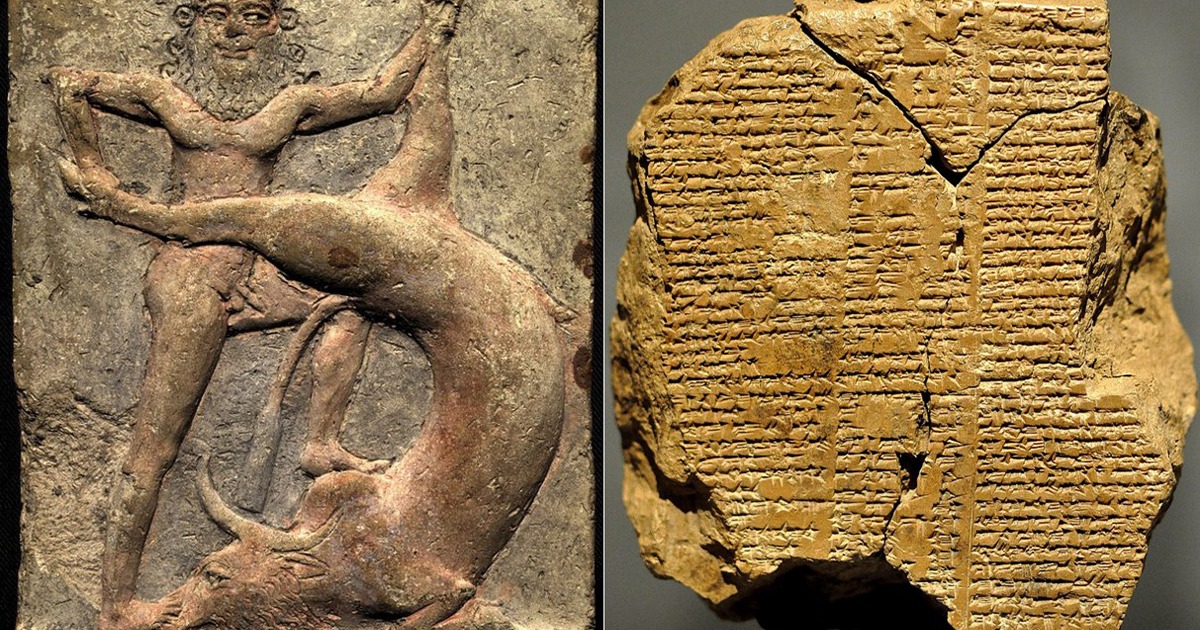

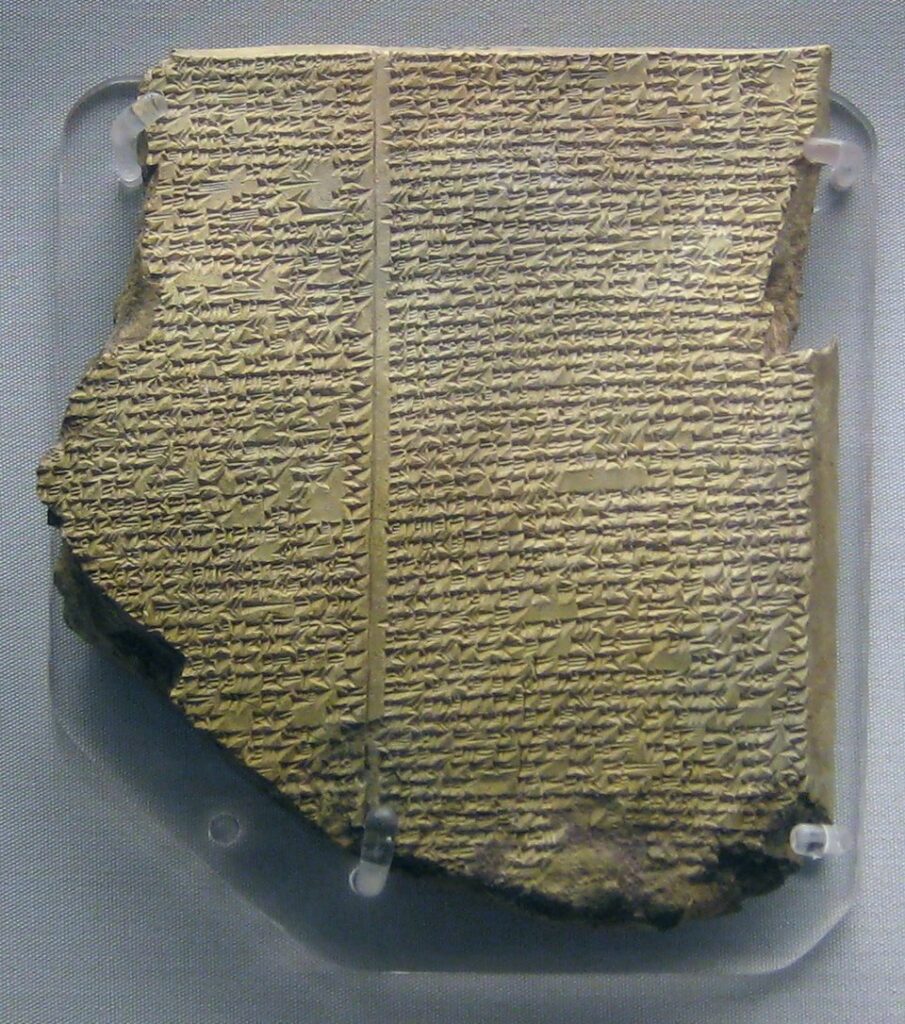

If you want a deeper dive into primary texts and artefacts, pair readable translations with museum catalogues. For orientation, try an overview at an academic museum site, then examine a single object with a high-resolution image. Build knowledge by looking hard, not by hoarding names.

Quick cross-comparisons that actually hold

- Sky order vs river order: Greek/Roman sky authority centres law and pact; Egyptian river cycles centre ritual maintenance. Norse tempers both with weather and war at the edges.

- Hero ethics: Greeks prize excellence and measure. Romans add duty and founding. Norse add courage in loss. Egyptians add right order validated by judgement.

- Fate: All accept limits. The language differs. The boundary stands.

- Afterlife: Moral sorting sharpens in Egypt and later Roman poetry; Norse sorting is by role and manner; early Greek Hades is quieter and more civic than moral.

Why comparison helps now

It cuts noise. It shows that repeated human problems attract repeated answers, and that each culture tunes those answers to local weather, law, and work. It also reduces lazy claims of sameness. You can respect difference and still learn. That is what these stories were for: teaching people how to live in places with wind, taxes, grief, hunger, hope, and neighbours.

Further reading and looking

Two practical habits improve understanding fast. First, read a primary text with notes. Second, stand in front of an object for ten quiet minutes. Museums, even online, are classrooms. A high-quality object page will often list material, technique, and context that change how you read a story. If you like quick reference, an accessible encyclopedia page can confirm dates and variants before you chase scholarship.

Finally, be gentle with certainty. These traditions were not handbooks. They were living conversations. Treat them like conversations and they start talking back.

FAQ: short answers to common questions

Are Greek and Roman gods the same?

No. Romans often identified Greek gods with Latin names, yet practice and politics differ. Jupiter is not just Zeus in another hat.

Is Norse myth a neat system?

It is a tapestry woven from many strands, written down late. Expect seams and layers. That is part of the appeal.

Did Egyptians believe everyone got judged the same way?

Yes, in principle. The weighing of the heart applies broadly, with texts and spells helping the deceased navigate the journey.

Why compare at all?

Patterns clarify local genius. You see what is unique by setting it next to what repeats.