Headlines like to shout. Reality tends to nudge. A decade ago, the idea that a DNA test could change the story of Viking warriors sounded like wishful thinking. Then a well-known burial from Birka—catalogued as Bj 581—produced a result that forced people to stop and read the small print. The person interred with sword, spear, axe, two shields, arrows, gaming pieces, and two horses wasn’t biologically male. The genome carried two X chromosomes and no Y. That single fact tightened every argument about gender and warfare in the Viking Age.

What follows isn’t a parade of clichés about “shield-maidens.” It’s about how one case moved from assumption to evidence; how critics pressed fair questions; and how the conversation matured. The DNA didn’t prove that all Viking women fought. It showed that at least one high-status weapons grave at the heart of a garrisoned site belonged to a woman. When combined with context, it suggests her role wasn’t ceremonial. From there, the debate widened—cautiously, as good scholarship should.

The burial that bent the narrative

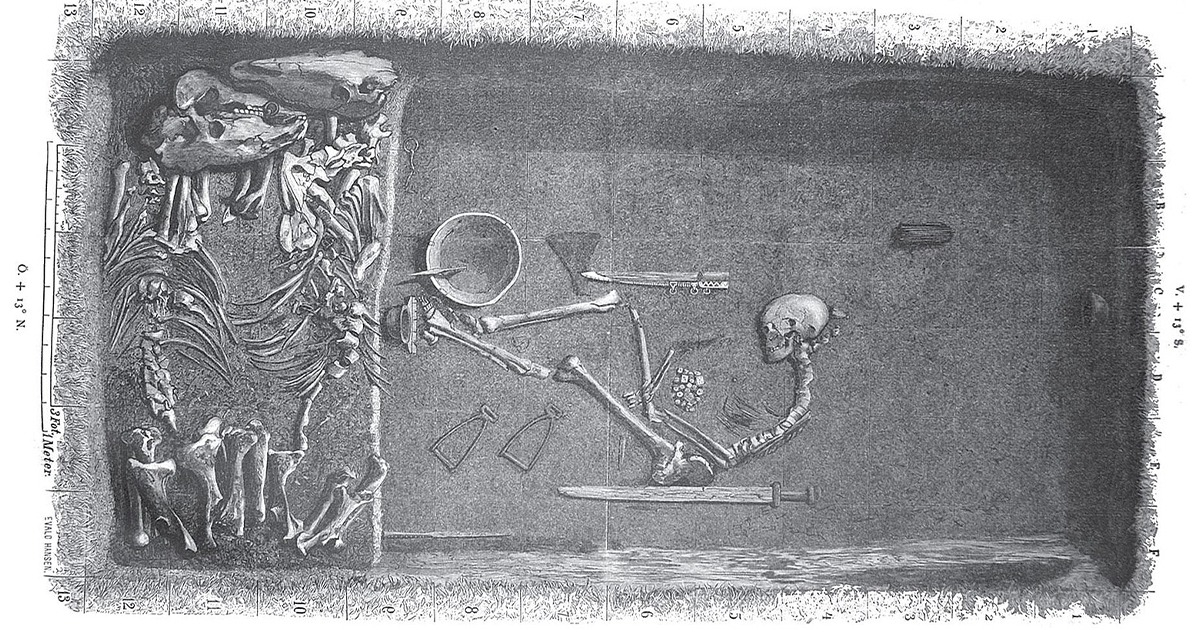

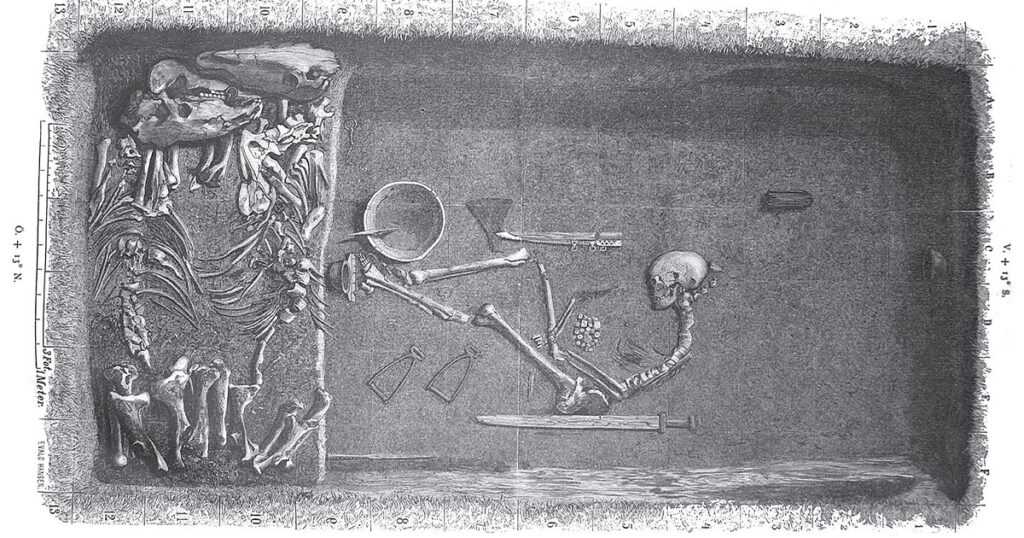

Archaeologist Hjalmar Stolpe excavated Bj 581 in the late nineteenth century. The chamber grave sat on an elevated terrace between Birka’s market area and a nearby hillfort. That real estate matters; graves cluster by status and function. Inside the chamber, the inventory reads like a field kit: sword, spear, axe, arrows built to punch armour, a sax, two shields, riding gear, gaming pieces and dice, plus two sacrificed horses. For over a century the skeleton was assumed to be male because the burial looked military. Assumption became habit. Habit hardened into “fact.”

Decades later, osteology raised an eyebrow. Pelvic and mandibular features looked female. Skeptics asked whether the bones and the grave goods had been mixed. Reasonable. DNA closed that door. Samples from a tooth and an arm bone confirmed chromosomal sex: female. Strontium isotopes added texture about mobility. The weapons were not props. The gaming pieces hinted at strategy and command. Each line of evidence was modest on its own; together they pointed in one direction.

What the DNA did—and did not—say

First, clarity. The study confirmed biological sex, not identity, not self-presentation, and not a résumé of battlefield acts. Yet archaeology rarely gets such clean anchors. When a weapon-rich grave in a garrison zone belongs to a woman, that undercuts a lazy equation of weapons grave = man. It also forces a re-read of the site: who lived by that hall, who trained there, and how roles mapped onto rank. The paper that announced the result argued for a professional warrior. Critics asked whether wealth or display could explain the goods. The authors replied with context—placement, kit, horses, and the density of combat gear nearby.

The most productive outcome wasn’t victory on social media. It was better questions. How often have bones from “weapons graves” been sexed with modern methods? How many “female graves” were labelled that way because a brooch sat on the chest while iron objects corroded to invisibility? How many mixed-sex cremations blur the picture? Once you start rechecking assumptions, data improves quickly.

Weapons, gaming pieces, and the grammar of rank

Grave goods don’t speak; context gives them a voice. Swords in the Viking world signal status as much as fighting skill, but a full set of functional weapons alongside riding gear tips the balance toward martial identity. The gaming pieces matter because they don’t turn up randomly. In elite burials they often travel with men who commanded. A board game set can signal planning, logistics, the habit of staging combat as a rule-bound contest. Taken together—with two horses, one stallion and one mare—the assemblage looks like a person embedded in a military structure, not a merchant accessorising for the afterlife.

Moreover, the grave’s neighbourhood speaks. Bj 581 sits within a landscape saturated with war-gear and close to a hall used by armed retainers. Birka’s “garrison” isn’t a loose metaphor. The island functioned as a proto-town, a market hub, and a node in networks that demanded protection. Security was organised, visible, and valued. That’s the setting into which this woman was buried.

So, were Viking women “warriors”?

That word can trip an argument before it starts. If “warrior” means someone tied to organised violence—trained, equipped, and expected to fight—then one famous weapons grave in such a setting belongs to a woman. If “warrior” means a person with a lifetime on campaign, the archaeological record can’t deliver a service record. What we can say is this: the assumption that women never occupied martial roles doesn’t survive contact with Bj 581, nor with a growing body of reevaluated burials across the North.

Beyond Birka, researchers have flagged other graves where sexing has shifted or where weaponry sits with female dress items. Some cases wilt under scrutiny; others hold up. A 2021 monograph rounded up dozens of examples of women with weapons, from Norway to Poland, arguing that our sampling and our bias both depress the count. Meanwhile, a 2019 reassessment of Bj 581 underscored the kit’s functionality and the grave’s military context. The direction of travel is steady: fewer certainties, more care, and a wider range of roles for women than the twentieth century allowed.

Method, not myth: why this case convinced so many

Three things made the difference. First, transparency. The team published methods, data, and reasoning. Second, replication. Independent specialists checked osteology, isotopes, and the genomic call. Third, context. The authors didn’t claim too much; they placed a single case within a living site. That model—open data, cross-checks, careful claims—turned an explosive headline into durable evidence.

Of course, debate didn’t vanish. Some archaeologists prefer the neutral phrase “weapons grave” to avoid loading the term “warrior.” Others emphasise how easily power and display can mimic competence. Those cautions are healthy. But they cut both ways. If display can masquerade as warfare, old assumptions can masquerade as fact. The value of Bj 581 is not that it proves a sweeping thesis. It prevents a sweeping denial.

Gender, labour, and martial work in a trading hub

It helps to picture daily life in a place like Birka. Traders arrive by boat with glass, silk, spices, and silver. Craftspeople hammer sheet metal into fittings and stitch imported cloth into status dress. Fighters—call them housecarls, retainers, or something nearer to police—patrol the margins where goods and envy meet. In such a town, martial labour is a job within a broader economy. It has ranks. It has pathways. It can be learned and taught.

Within that structure, a woman could occupy a military role without overturning the social order. Saga literature imagines “shield-maidens,” but we don’t need poetry to grasp a simpler point: complex towns grow complex roles. Household leadership, trade brokerage, religious authority, and armed service can overlap in one life. A burial like Bj 581 doesn’t feel like myth in that light. It looks like a professional identity captured in a single room of earth and wood.

How the story travelled—and why it matters now

When the DNA result landed, global media raced to tidy the narrative: “Viking warrior queen.” The studies themselves were less breathless. They treated the result as a data point with heavy implications, not an endpoint. Over time, the coverage improved. Long-form pieces looked at the wider pattern: re-sexed skeletons, revised catalogues, and a drift away from rigid gender binaries in the interpretation of grave goods. Museums updated labels. University courses adjusted slides. Students asked better questions.

Meanwhile, methods matured. Ancient DNA labs scaled up. Osteologists refined sex estimation across populations. Isotopes mapped mobility with greater nuance. None of this is a Viking story alone. It’s a case study in how new tools can unpick old assumptions across the ancient world, from Etruscan tombs to nomad graves on the steppe.

Common objections, answered briefly

“Could the bones have been mixed?”

That question came first. Researchers traced provenience carefully and matched multiple samples. The osteology and the DNA point to the same individual. Provenience control was strong enough to satisfy reviewers and most specialists.

“Maybe the weapons were symbolic.”

Possibly, but context weighs against it. The grave lay by a garrison hall in a weapons-dense zone. The kit is comprehensive and functional. The two horses strengthen the military reading. Symbolism always has a role in burials; here, the symbolism aligns with a life tied to arms.

“One case doesn’t change a culture.”

True. One case changes the set of allowable claims. It shows that women could occupy high-status martial roles in at least one Viking community. That opens the door to re-testing other cases rather than closing the file.

What to watch as research expands

Fresh surveys of museum collections are already turning up mislabelled remains. As labs revisit legacy burials with better sampling and better contamination control, the dataset grows. We’ll see more cautious language—“probable,” “possible,” “consistent with”—because that’s how science hedges uncertainty. Expect papers that compile dozens of sites with updated sex determinations and re-weighted interpretations of grave goods. Expect arguments too. That’s healthy.

We will also see more attention to non-combat roles in military systems: logistics, intelligence, diplomacy, medical care. Those jobs sit in the same households and halls. They leave different traces than a blade, but they stitch warfare to everyday life. If the conversation moves beyond the stark yes/no of “warrior,” it will become more accurate—and more human.

Why readers outside academia should care

Because stories about the past shape what we allow in the present. If we insist that certain jobs “never belonged” to women, we smuggle a myth into our sense of possibility. The point isn’t to mint heroes for the sake of it. It’s to keep the door open where evidence says it belongs open. Bj 581 does that. It complicates a picture that was too tidy, and it reminds us to reread old notes with new eyes.

History advances by details. A pelvic notch. A strand of DNA. The position of a horse skull in a chamber. Together, such things make and unmake narratives. In this case, the details show that the Viking world had room—perhaps not common, but real—for women whose identities included martial power. That’s enough to retire the claim that “it never happened.” It didn’t happen everywhere. It happened here.

Final take

When a weapons grave by a garrison yields a female genome, the burden of proof shifts. You no longer have to argue that a woman might have been a warrior in the Viking world. You can point to a grave and say that in at least one time and place, a woman occupied a military role integral enough to be buried with its tools. That’s not a slogan; it’s a sober reading of the record. The story will keep evolving as more graves are tested. For now, the lesson is clear: evidence beats assumption, one bone and one context at a time.