Who owns the past? The question is easy to ask and difficult to answer. It touches law, identity, scholarship, diplomacy, and the public’s right to learn. Ancient objects have passed through wars, empires, markets, museums, and courts. Some were seized; others bought; many were excavated under older regimes; a few have been returned after long campaigns. This guide maps the landscape in plain language so readers can follow the arguments, assess evidence, and see where careful common ground is possible without glossing over harm.

We will separate legal title from cultural belonging, and keep three lenses in steady focus throughout: colonialism (how power structured acquisition), nationalism (how states claim the ancient for identity and legitimacy), and stewardship (how scholars and communities care for objects now). The aim is not to score points. It is to show workable paths between all-or-nothing positions while staying honest about history and the people it touches.

What does “ownership” mean for ancient objects?

Ownership can be several things at once. There is legal title, held by a person or institution under a state’s law. There is cultural affiliation, the lived ties that communities claim to makers, meanings, or places. There is custody, the practical care of storage, conservation, and display. And there is stewardship, the ethical duty to preserve, research, and teach. Confusion begins when any one of these is treated as the whole story, or when today’s values are projected onto yesterday’s rules.

Modern heritage regimes reflect that complexity. Export laws, excavation permits, and international agreements try to reduce harm and structure cooperation. They cannot rewrite the past, but they can shape the future: how museums acquire, how scholars publish, how countries negotiate, and how communities regain a voice in telling their own histories.

Colonialism: routes by which antiquities moved

Under imperial rule, objects left their contexts by many routes: outright seizure in war; coerced “gifts”; divisions of finds under partage systems that favoured European institutions; purchases in asymmetrical markets; and the export of monumental pieces as trophies. Catalogues often polished these movements as “acquisitions.” The power imbalance is hard to miss, and the afterlives of those choices still shape galleries, scholarship, and national memory.

At the same time, not every object now in a European or North American museum was stolen. Many were excavated under the laws of the day; some were sold legally by private owners; others were exported before modern rules existed. Sorting this out is the historian’s job: document the chain, set the context, compare the law then and now, and acknowledge gaps where the paper trail breaks.

Nationalism: how states claim the ancient

Modern states often build identity through antiquity. Monuments and myths signal continuity, legitimacy, and uniqueness. That pride can fund research and conservation; it can also sharpen disputes. Appeals to “civilizational ownership” risk flattening multi-ethnic pasts or excluding diaspora voices. Even so, national museums shoulder real responsibilities: protecting sites from looting, training conservators, and teaching history in public. The hard work is to support care without sliding into exclusivity, and to treat restitution as policy, not propaganda.

Law and ethics: the frameworks that set the ground

Three instruments guide current practice. The 1954 Hague Convention protects cultural property in armed conflict; the 1970 UNESCO Convention addresses illicit import, export, and transfer of ownership; and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention supplies private-law tools for restitution and return. Ratification maps differ, terms vary, and many famous removals predate these texts; nevertheless, they anchor museum policy, court cases, and diplomacy today. (See key references in the resources section.)

Why provenance research matters

Provenance—the documented history of an object—turns claims into evidence. Exact findspot, date of export, permits, dealer invoices, exhibition records, and past publications all matter. A short, clean provenance builds trust; a long, broken trail demands caution. When records are thin, responsible institutions publish what they know, invite leads, and adjust labels accordingly. “We do not know” is honest—and an invitation to the public to help complete the story.

Case studies and what they teach

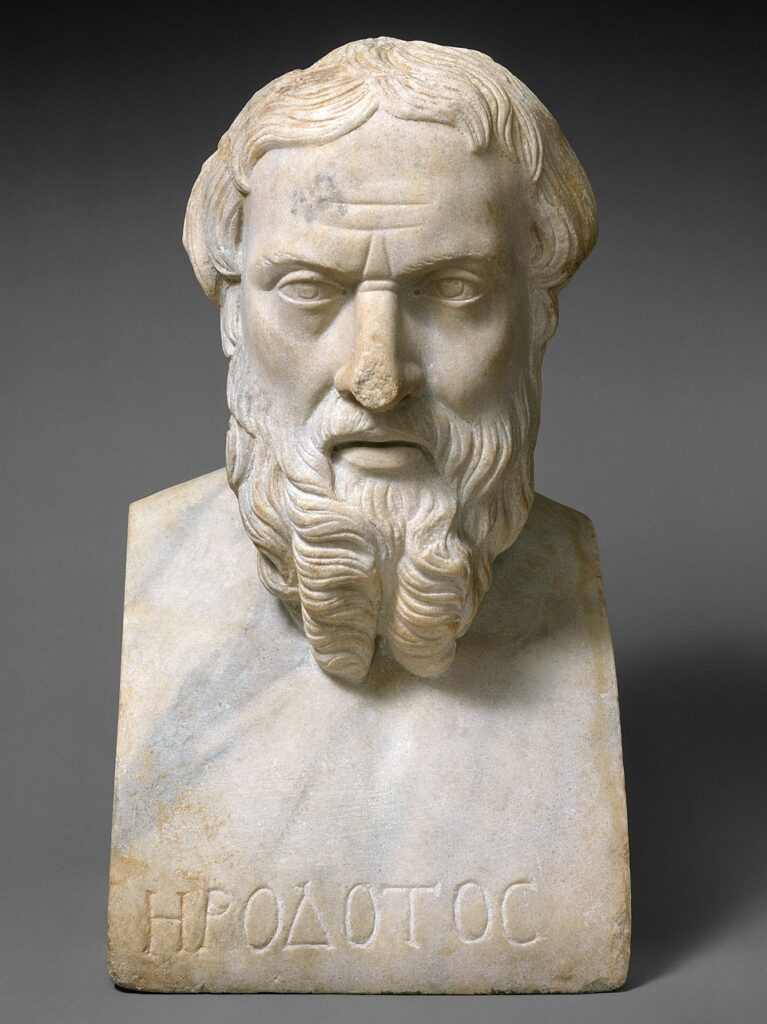

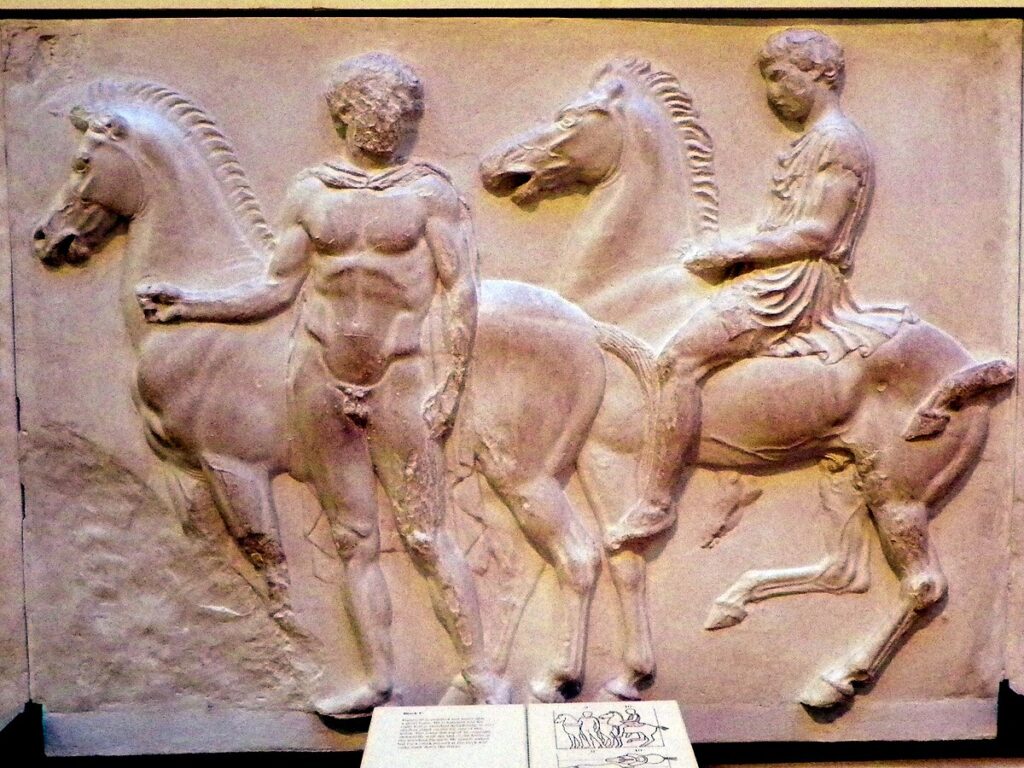

Parthenon sculptures (Athens & London)

Supporters of return argue that the sculptures are integral parts of a single monument and therefore belong in Athens, where light, scale, and meaning reunite. They stress Ottoman-era permissions as invalid or ambiguous and point to conservation mishaps as evidence of harm. Defenders of the British Museum stress acquisition under the norms of the time, universal access in a global museum, and the value of seeing the sculptures in comparison with other civilizations. Teaching point: define the date and mode of removal, the law then and now, the condition history, and the public-interest trade-offs clearly.

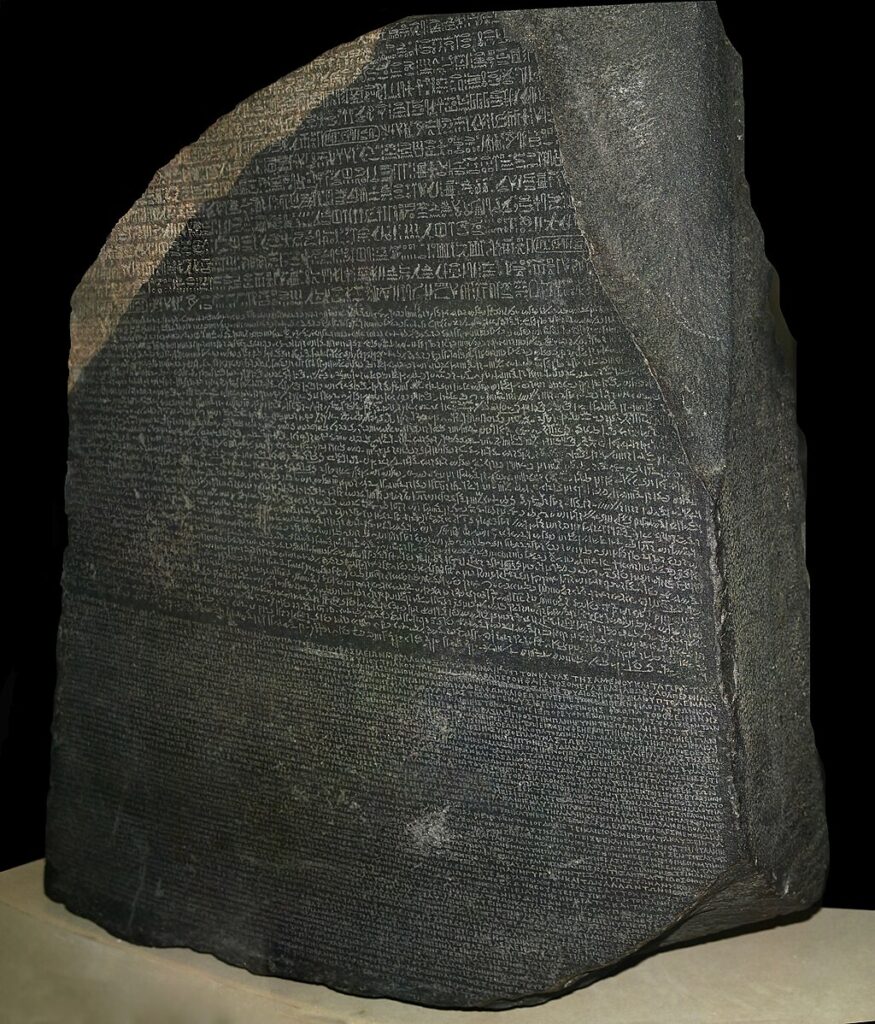

Rosetta Stone (Cairo & London)

The stone enabled the modern reading of hieroglyphs, reshaping Egyptology and public understanding. Egypt’s case emphasises removal under foreign occupation and the object’s singular role in national heritage. The British Museum stresses legal succession under early nineteenth-century treaties and the benefits of global display. Teaching point: many disputes hinge not only on legality but on symbolism. Good policy treats symbols with care while protecting open access to knowledge.

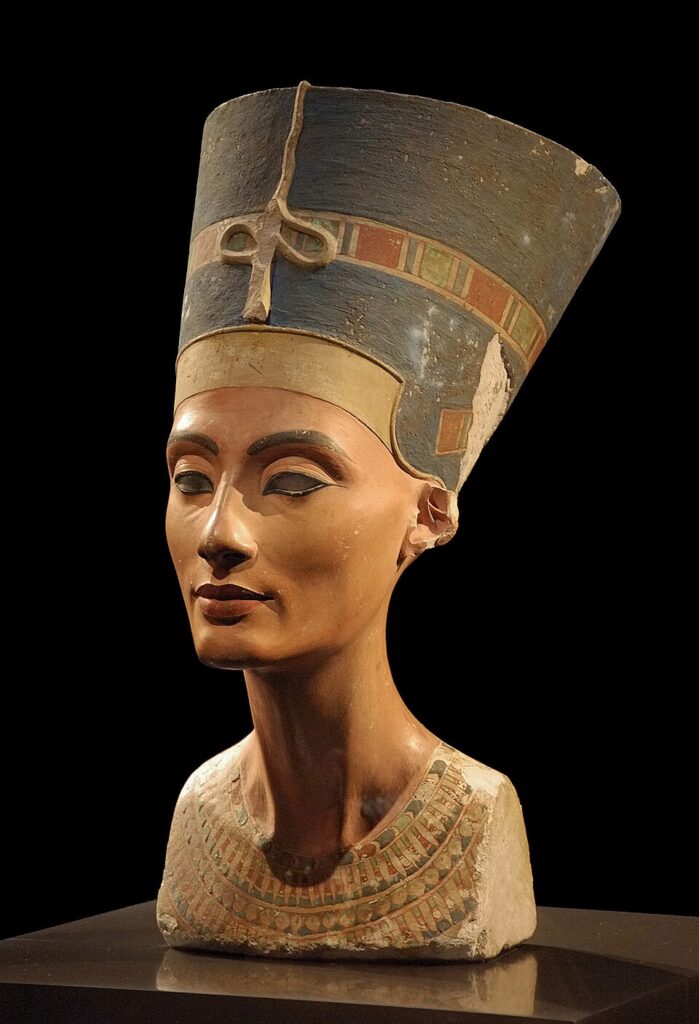

Nefertiti bust (Berlin & Cairo)

One sculpture, many meanings: Amarna art, a queen’s image, a museum icon, and a diplomatic headache. German records point to division of finds; Egyptian authorities argue concealment or bad faith. Digital surrogates complicate the field: high-resolution scans widen access and can ease pressure on the original, but they do not settle custody. Teaching point: even perfect 3D models cannot replace living ties; they can, however, support shared stewardship and research.

Pergamon Altar & the Ishtar Gate (Berlin)

The Pergamon Altar’s great friezes and the reconstructed Ishtar Gate are magnets for visitors and flashpoints for critics. They were moved to Berlin under late-Ottoman laws and excavation agreements; today, Iraq and Türkiye emphasise context, integrity, and national heritage. German curators highlight documented permits, conservation, and public study. Teaching point: early legal frameworks were real, and imperial pressures were real. A serious approach keeps both truths in view and looks to practical instruments—generous long-term loans, co-curation agreements, transparent labels, shared research, and regular rotations—to serve access and dignity together.

Obelisk of Axum (Aksum) — a return

Not every story stalls. The Aksum obelisk, taken to Rome in the 1930s, returned to Ethiopia in 2005 after a complex, cooperative project managed with international support. The re-erection was both a technical feat and a symbolic act, showing that restitution can be planned, safe, and constructive for all parties. Teaching point: well-resourced partnerships make return feasible and educative.

Cyrus Cylinder (London & Tehran) — shared access

The clay cylinder credited to Cyrus II has travelled on long-term loans to Iran and toured widely. While it remains in London, collaborations around exhibitions, research, photography, and translation have multiplied access. Teaching point: loans and joint programmes are not a cure-all, but they often deliver immediate benefits across borders while larger questions are negotiated in good faith.

How scholars separate legend, law, and lived ties

First, reconstruct context. Where was the object found, when, and by whom? What laws applied at the time? Was there a division of finds? Did a permit specify export? Context sharpens ethical arguments and legal options.

Second, test provenance. Gather dealer records, export licences, old photographs, exhibition catalogues, and publications. Gaps do not automatically condemn; they do shift the burden of proof. Responsible institutions publish uncertainties and invite corrections, then update labels as evidence improves.

Third, weigh public interest and community voice. Access, research value, and conservation capacity all matter. So do descendant, Indigenous, and local community ties that museums ignored for generations. Durable solutions put these on one table and make them visible to the public.

Finally, design practical arrangements. Returns; renewable long-term loans; rotating displays between partner museums; joint field projects; digitisation at source; training and funding for regional labs; and bilingual labels that credit origin communities. Policy becomes real when it is specific, resourced, and scheduled.

Common mistakes that stall progress

- All-or-nothing framing: “Return everything” vs “return nothing.” Most cases sit in the middle and benefit from staged, monitored solutions.

- Presentism: Judging nineteenth-century permits as if modern conventions applied. We can condemn injustice and still read older law accurately.

- Legalism without ethics (or ethics without law): A clean title does not erase harm; a moral claim does not override every legal system. Pair both and show your working.

- Silence about uncertainty: When records are thin, say so. Invite leads. Update labels. Reward good-faith contributions.

What “universal museums” can be—if they adapt

Large encyclopaedic museums can model good practice: refuse acquisitions with weak provenance; publish full object records online; label colonial histories plainly; co-curate with origin communities; fund fieldwork and conservation at source; share revenue from image licensing; and commit to long-term loans that put masterworks back in origin cities on a regular calendar. “Universal” should describe access and cooperation, not ownership by default.

Digital access: useful, not sufficient

Open images, 3D models, and virtual tours widen public reach and help teaching. They do not replace the legal or moral questions, but they lower the stakes around travel and display while negotiations continue. Good digitisation also documents condition, supports conservation, and reduces handling risks. The principle is simple: and, not instead.

Teaching the controversy well

For classrooms and galleries, clarity helps. Fix the date and mode of removal; outline the laws in force then and now; list the stakeholders; state the object’s current location and policy; and present at least one workable alternative. Students learn that heritage disputes are design problems with solutions, not permanent shouting matches.

Practical checklist for readers

- Identify the object, maker/culture, and findspot if known.

- Establish removal date and the laws then in force.

- Trace provenance and flag gaps.

- Name stakeholders: origin state, origin communities, holding museum, researchers, and the public.

- List options: return, shared custody, long-term loans, joint exhibits, digital surrogates.

- Ask which option best protects access, knowledge, and dignity—and who is accountable for delivery.

Why this matters

Ancient history is not only about the past. It is about handling the dead with care, the living with respect, and knowledge with patience. Good policy protects sites and people today and improves scholarship tomorrow. That is the work behind the headline: not possession, but responsibility. When we ask who owns the past, a better answer is: who will care for it, share it, and tell it truthfully.

Explore collections: British Museum Collection · The Met Open Access.