From Myth to History is not a demolition job on old stories. It is a disciplined way to read them: identify what kind of text or image you are looking at, place it in time and social use, and then test its claims against other evidence. When scholars say they have moved from myth to history, they mean they have turned narratives that carry ritual, identity, or memory into questions that can be checked—by texts, objects, landscapes, and science. The result is not cynicism. It is clarity. This guide explains the method as working historians use it: source criticism, genre awareness, archaeological context, epigraphy and papyrology, scientific dating, and cross-comparison. It also shows why legend remains valuable: myths preserve priorities, fears, and hopes that archives alone cannot store. The craft lies in refusing to flatten either side. We take myth seriously as myth; we extract history where the evidence is strong; we mark the edges where the trail runs thin.

Why “myth” is not the enemy of “history”

In ancient worlds, myth is a language for truth claims that do not fit minutes or receipts. Founders, floods, city gods, golden ages—their details vary, but their work is similar: to explain why a people belongs in a landscape and what behaviour counts as loyal. From Myth to History does not ask myth to be a modern report. Instead, it asks: what kinds of truth does this myth claim, and which parts touch events or institutions we can test? For a wider map of traditions, see Comparative Mythology: Greek, Roman, Norse, Egyptian. Separating legend from reality begins by sorting functions. A funerary hymn is not a boundary stone. A king list is not a lament. Each form carries its own rules of evidence and its own relationship to the past. Once we respect those rules, we can start to look for anchors: names, regnal years, place-names, treaties, tax lists, coin hoards, ruined walls.

How evidence is built: the historian’s toolkit

Good history is cumulative. No single object proves a grand claim. Instead, we look for convergences, where independent lines of evidence point in the same direction.

1) Source criticism and genre

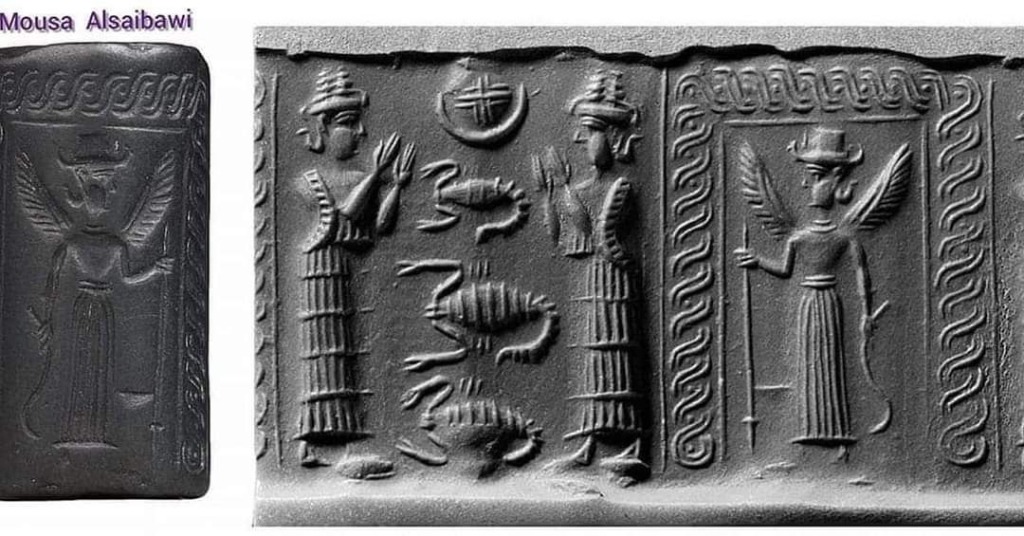

Who produced the text or image, for whom, and why? Is it epic poetry, a dedication, a law code, a temple relief, a votive graffito, a letter, a king list? We read with the right expectations. Herodotus mixes travel report, oral tale, and moral reflection. Egyptian battle scenes record victory as cosmic duty. Hittite treaties preserve clauses and witnesses. Each genre asks different questions and tolerates different kinds of exaggeration. For story structure in epics, see The Hero’s Journey in Ancient Myths.

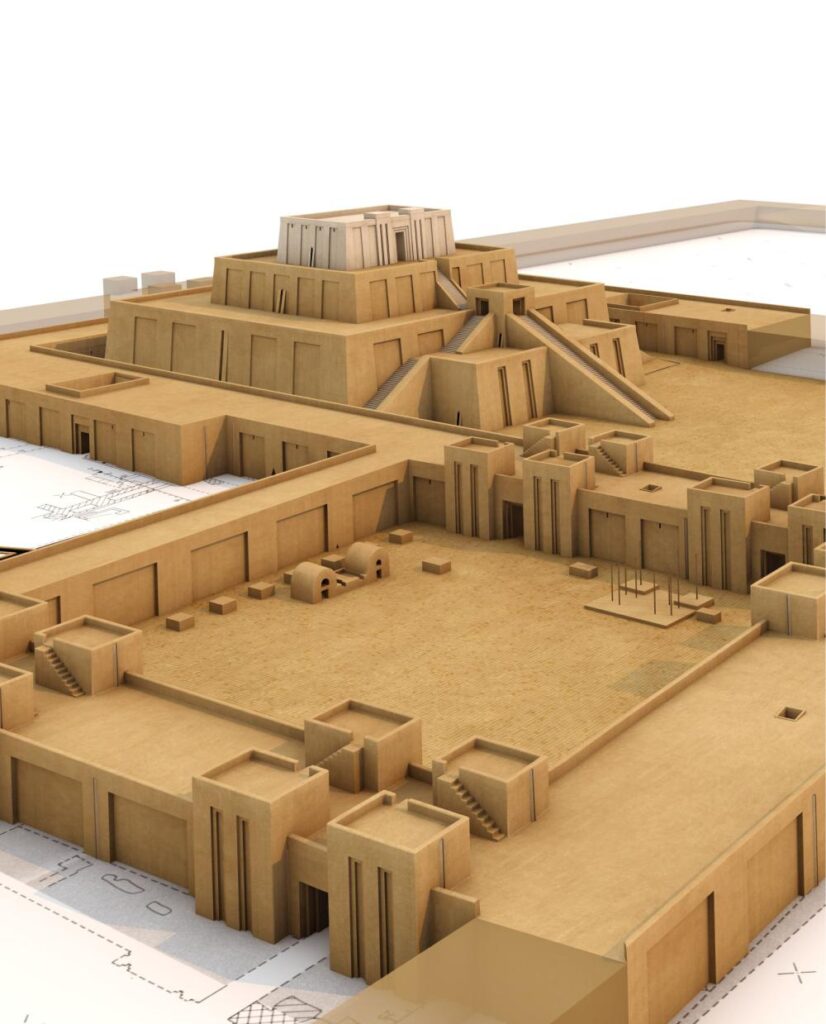

2) Archaeology and context

Objects are persuasive only when we know where they were found, in what layer, and with which neighbours. A spearhead without a context is a curiosity; a spearhead inside a sealed destruction layer next to sling bullets and fire debris is a battle. Excavation phases, stratigraphy, ceramic sequences, and radiocarbon anchors turn objects into timelines. Context moves us from myth to history because it links story to soil. For biomolecular casework tied to ritual sites, compare Göbekli Tepe 2025: Biomolecular Clues.

3) Epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics

Inscriptions write institutions into stone: decrees, boundaries, taxes, titles, names. Papyri catch everyday life: receipts, petitions, leases, letters. Coins speak about authority, economy, and self-presentation—who mints, what image claims legitimacy, where coins travel, how they are clipped or countermarked. This documentary layer tests or corrects literary memory. For movement across regions, see Ancient Trade Routes.

4) Scientific methods

Radiocarbon dating framed by Bayesian models situates organic remains; dendrochronology adds year-level precision where wood survives; stable isotopes track diet and mobility; aDNA reveals kinship and population movement. Science does not replace history. It refines the dates and tests narratives for plausibility. When told carefully, it does not outrun its resolution or pretend to answer questions it cannot see. For examples, compare aDNA and diet work in Neanderthal Medicine Rediscovered.

5) Linguistics and place-names

Languages leave tracks: loanwords, sound shifts, and names that stick to rivers and hills. A heroic tale set at a site with an ancient non-Greek toponym suggests deep continuity beneath later story paint. Linguistic work rarely “proves” a legend, but it narrows the field of what could have happened and when. For decipherment breakthroughs and limits, see AI Deciphering Linear A (2025) and a cautionary counterpoint in Rongorongo: Why Decipherment Keeps Failing.

Case studies: where legend meets the record

Troy and the long argument

For centuries, Troy lived as poetry. Excavations at Hisarlik, however, revealed a complex citadel with multiple destruction layers. The site does not “prove Homer,” and Homer does not inventory the site. Yet when fortifications, fire levels, regional upheavals, and Hittite texts mentioning a place likely to be Wilusa align, historians move from myth to history responsibly: there was a powerful city; it suffered violent episodes; late Bronze Age politics in the region were real. The story’s poetic core survives, but its edges sharpen. As a related line of evidence about post-war diaspora, see our note on a Trojan-linked community in The Lost City of Tenea.

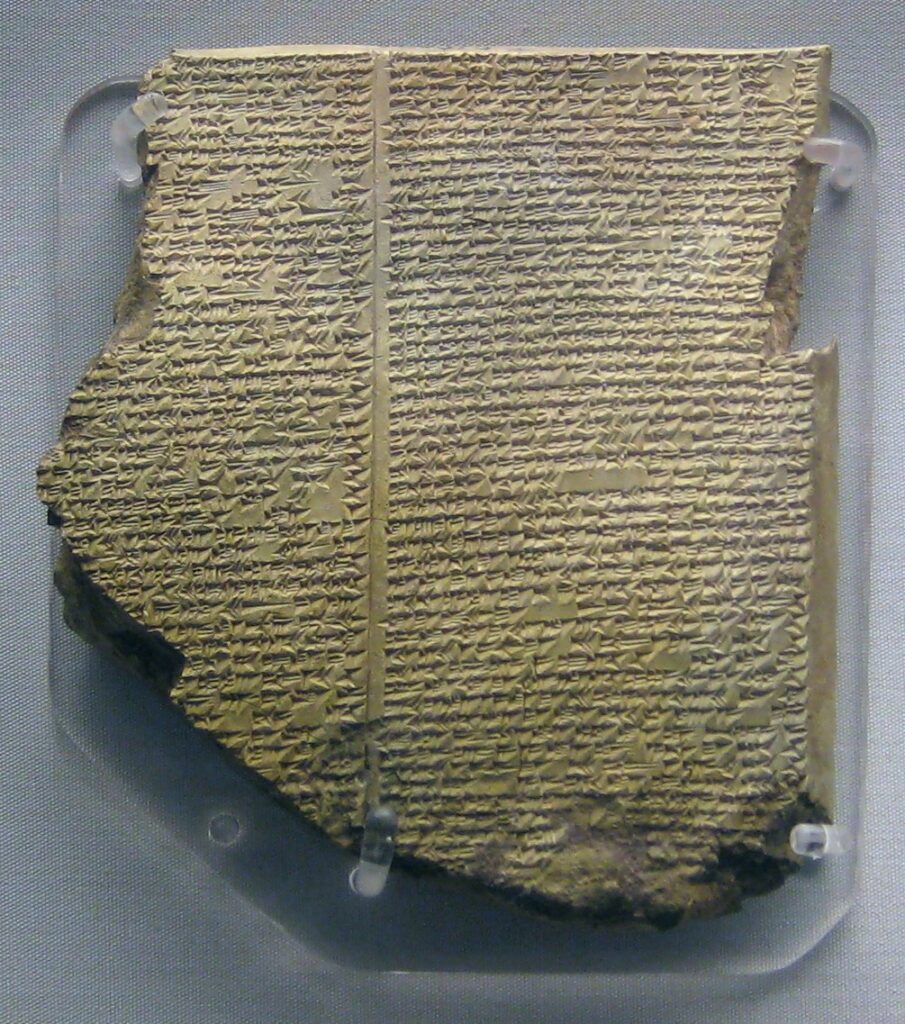

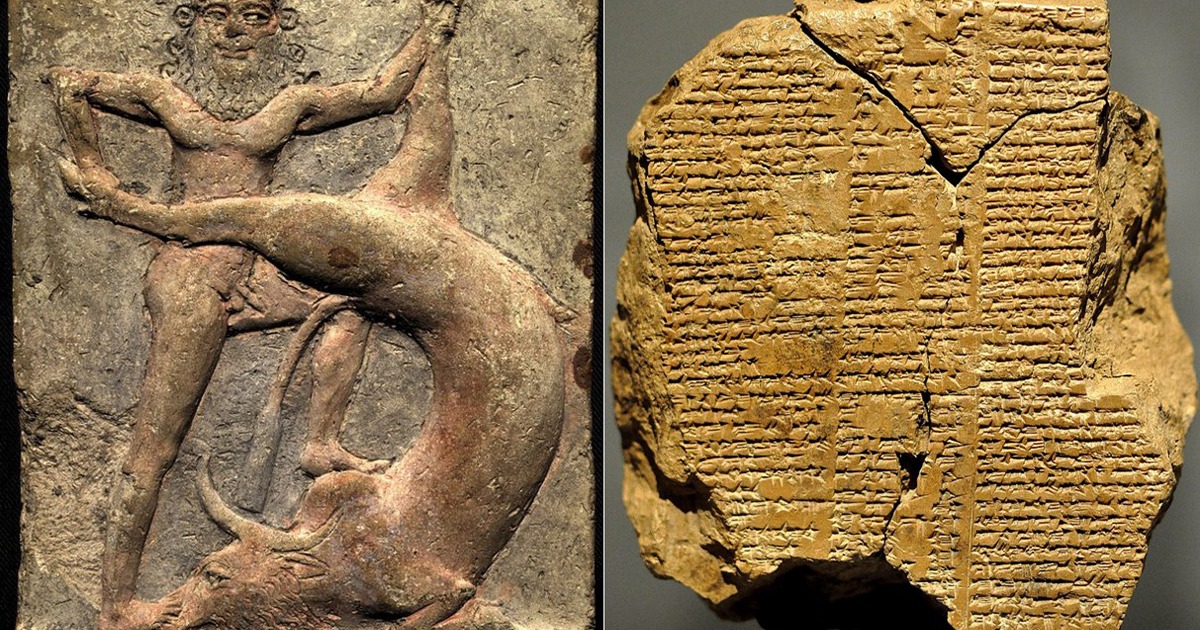

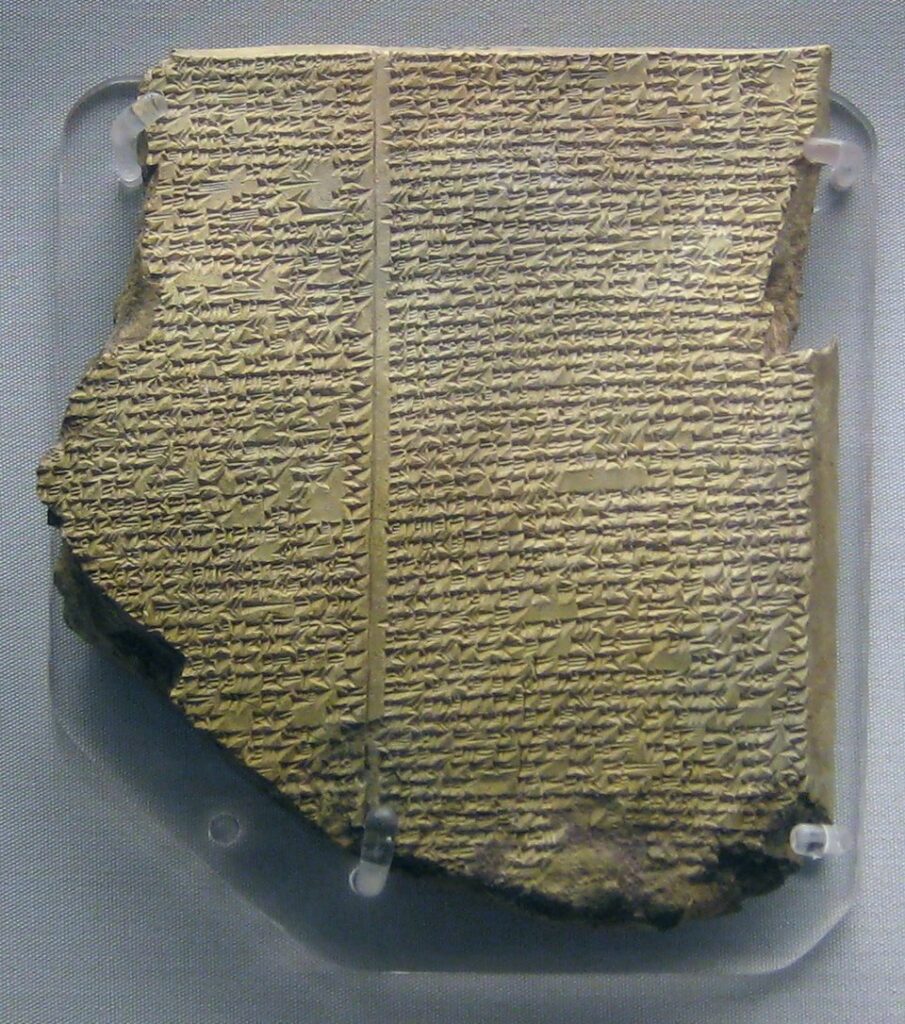

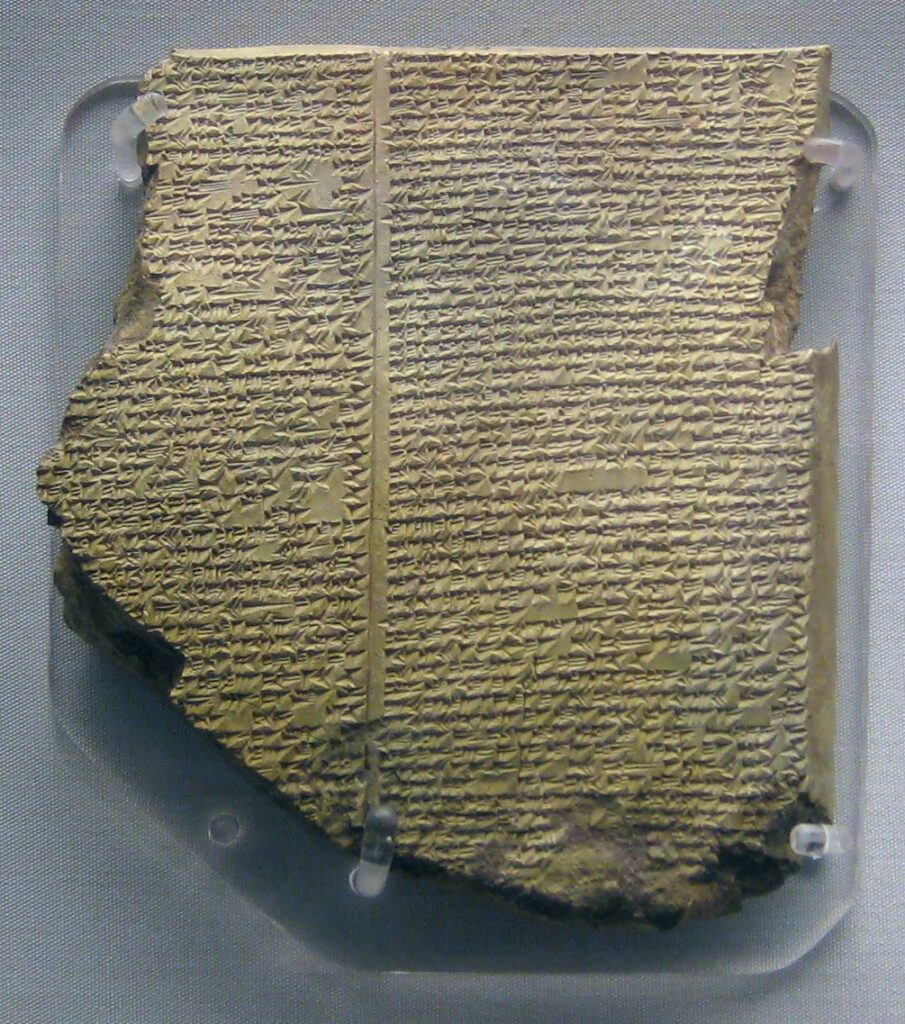

Gilgamesh: a king behind the epic

The historical kernel of Gilgamesh likely sits in an early dynastic ruler of Uruk. The epic, compiled over centuries, wraps him in cosmic quests and flood wisdom. Clay tablets, king lists, and archaeological layers at Uruk confirm the city’s scale and ambition; they do not ask us to believe in immortal plants. Still, the epic’s grief and city pride record social truths we can map: urban labour, friendship under risk, and the limits of royal power. For Mesopotamian mythic figures that shaped later memory, compare the Apkallu traditions.

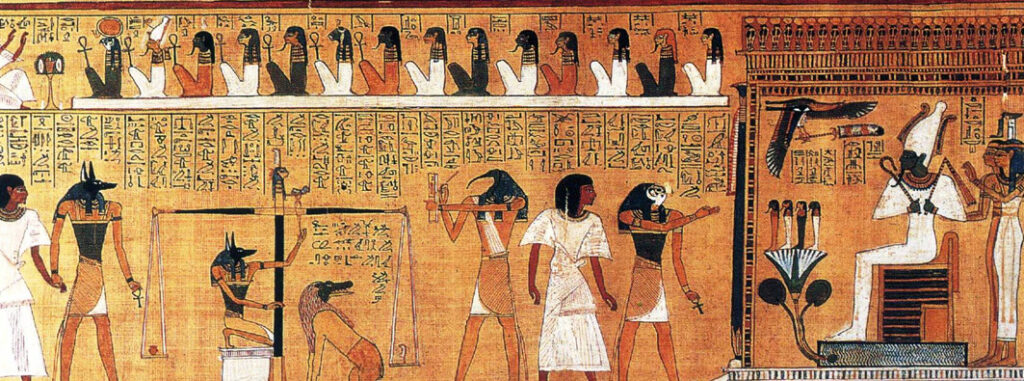

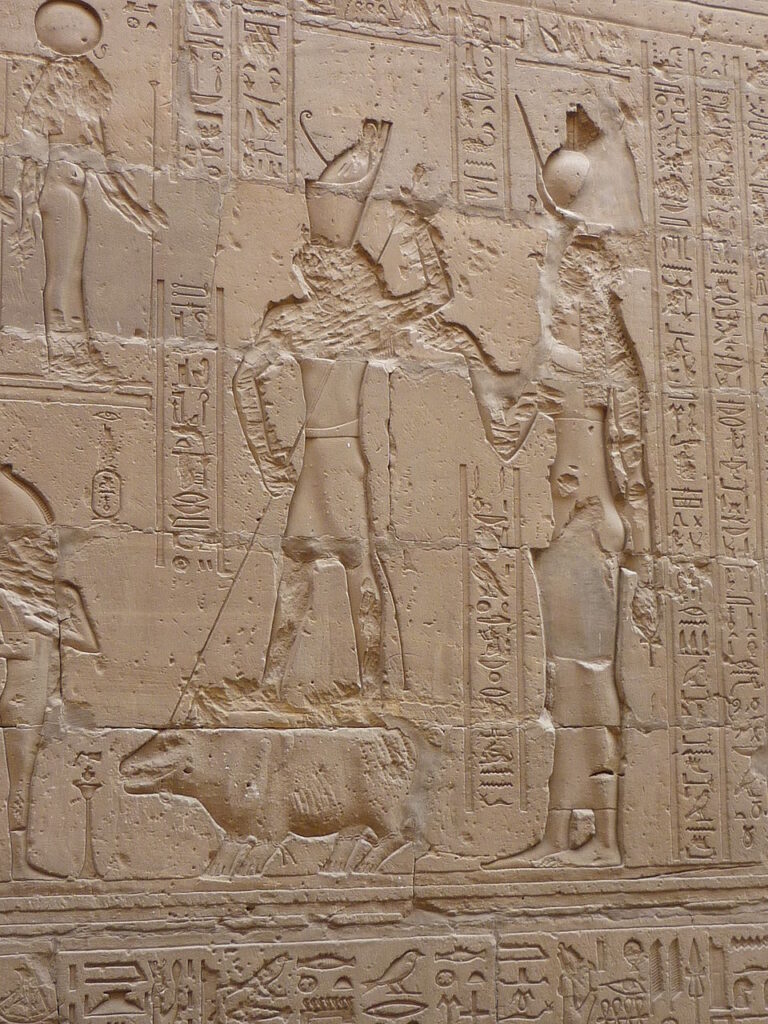

Ramesses II at Kadesh: victory, propaganda, and a treaty

Egyptian reliefs proclaim triumph; the Hittite treaty and duplicate Egyptian copies show a negotiated stalemate. Reading both sides, alongside topography and chariot archaeology, moves us away from simple boasts toward the political reality of parity. Here mythic self-presentation—king as guarantor of cosmic order—sits on top of a documentable diplomatic outcome. For the mechanics of state image-making, see Julius Caesar’s PR Machine.

Rome’s foundations: wolves, hills, and the Palatine

Romulus and Remus are narrative glue. Archaeology on the Palatine shows hut foundations and early walls consistent with a nucleated community in the period later Romans imagined. Ritual calendars, foundation myths, and political memory in Livy do not become “false” because huts are small; nor do huts “prove” a she-wolf. The method respects both: myth articulates values for rule and kin; archaeology marks when a hill turns into a city. For the long arc of state-building that followed, see How Rome Built an Empire That Lasted 1000 Years.

Decipherment and the power of parallel texts

Sometimes legend yields to history when scripts fall open. The trilingual Behistun Inscription let scholars read Old Persian and, later, Akkadian cuneiform reliably. Once records became legible—campaigns, building lists, tribute—it was possible to test royal claims, date events, and compare neighbours’ testimonies. Decipherment does not make texts neutral, but it gives them back their voice. For successes, see Linear A AI attempts in 2025; for limits, see Rongorongo’s stalled decipherment.

Method, step by step (without turning it into a checklist)

We do not need “ten ways.” We need a sequence we can defend. Start with form and setting. Name the genre, date, and probable audience. Ask what the text or image is trying to do in its first life. A hymn pleases a god and a crowd; a treaty binds two kings; a boundary stone frightens trespassers. These purposes shape what can be trusted and how. Stabilise the chronology. Use radiocarbon ranges and ceramic phases to frame layers; add inscriptions and coin series for tighter anchors; let dendrochronology or eclipse records refine the line where possible. Chronicle first; argument second. Find independent points of contact. A place-name in a poem, a river crossing in a relief, a tax rate in a papyrus—none is decisive alone. Together, they form a lattice. When a story lands multiple times on that lattice, confidence grows without claiming certainty. Resist the neat fit. Some parts will never meet the checkable world. That is fine. Ritual animals, divine visitations, marvels—these tell us about values and metaphors. To force them into a file of proofs is to ruin both myth and method.

Common errors that keep legend and reality tangled

Presentism. Reading ancient stories as if they were op-eds on today’s politics is quick and tempting. It also erases their own problems and solutions. Responsible comparison isolates the ancient question first and then, carefully, uses it to think about now. Argument from silence. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Archaeology is uneven; papyri rot; inscriptions break; chance saves the oddest things. Silence can constrain claims, but it cannot settle them without positive indicators. Single-source triumphalism. An object with a headline should not run the whole argument. The “Mask of Agamemnon” remains beautiful whether or not it touches Homer’s king. We win from myth to history when multiple sources carry modest claims together. For a worked example of checking a dominant narrative, see Masada vs Josephus: Archaeology vs Text. False precision. Bayesian models are not magic; radiocarbon dates are ranges; genetic signals are population stories, not passports with names. Use numbers to narrow; never to pretend certainty where the material cannot support it.

What science adds—and what it does not

Radiocarbon and dendrochronology frame events; isotopes test migration and diet; aDNA shows kinship and large-scale movement. These methods shift debates: migration versus diffusion, continuity versus replacement, famine versus trade reorientation. Still, science answers the questions its samples can see. It does not declare whether a god “exists” in a story, nor whether a miracle happened. It can, however, date a layer, identify a parasite, trace a herd, match a corpse to kin in a tomb. That is already transformative. For climate-tech from antiquity, compare Roman concrete’s modern relevance.

Why legend remains valuable after the audit

Even after we cut a story free from the duty to inform us about events, it continues to tell truths. Founders raised by wolves say something about how Romans imagined toughness, nurture, and law on a knife-edge. Battle reliefs that always win say something about the cosmic burden kings claimed. Floods that cleanse and restart say something about fear, hope, and justice. For symbols and beings across cultures, browse Mythical Creatures A–Z. From Myth to History is not a downgrade. It is a double reading, where metaphor and measurement face each other without embarrassment.

Teaching and writing with integrity

When we teach or write, we can model the craft: Say what you know and how you know it. “Excavation phase IV, dated 1250–1180 BCE by radiocarbon and ceramics, contains sling bullets and fire damage; Hittite texts refer to Wilusa in roughly the same period.” That is better than “Homer was right,” yet it lets a reader feel substance. Admit limits. “No inscription names Romulus in the 8th century BCE; the story’s earliest versions we have are later; but huts and fortifications on the Palatine align with a shift from villages to a city.” Limits are not weakness; they are the edge of the map. Split the claim. Separate what you infer about events from what you read about meaning. “The treaty existed; the relief claims a cosmic victory.” Both can be true in their registers. For a structured overview of the field, see Ancient History: A Practical Guide.

Frequently asked questions

Does moving from myth to history “disprove” ancient religion?

No. The method answers questions about events, institutions, and timelines. It does not adjudicate metaphysics. It can show when a cult starts, how it spreads, and how its rituals shape cities. That is history’s job.

Can archaeology ever “prove” a literary episode?

Rarely, and only in strict senses: a named place, a building phase, a destruction layer, a treaty text. What we usually gain is plausibility, sequence, and scale. That is a win.

How should conflicting sources be handled?

Do not average them. Read each in its own purpose and audience; then test their checkable parts against independent anchors. Let the remainder stand as perspective, not data.

Further looking and reliable object pages

To practice the method, pair texts with open collections that provide context fields, measurements, and provenance notes. Explore the British Museum collection and The Met’s Open Access collection; both maintain detailed records that help you move responsibly from myth to history.